Chapter 6: Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of Religion

Matthew Van Cleave

Does God exist?

The question of whether god[1] exists may seem like a fairly straightforward one: either there is a god or there isn’t. However, how one answers this question depends in large part on how one defines “god” and the fact that people have very different concepts of what god is complicates the matter. Muslims believe that the term “god” refers to a single unitary being that is all-powerful, all- knowing, and perfectly good. Christians believe that “god” refers to a Trinity— three different “persons” that are also (somehow) one being. Jews believe that “god” refers to a unity, like Muslims do, but disagree with Muslims that Muhammad was a prophet (a representative) of god. And this is only to mention the so-called “Abrahamic” traditions that uphold somewhat similar conceptions of god! Other traditions like the Buddhist, Hindu, or ancient Mesoamerican traditions uphold conceptions of gods that differ even more fundamentally from the Abrahamic conceptions. Traditions like the Hindu and ancient Greek religious traditions are polytheistic, meaning that they believe that there are many different gods, not just one. Some religious traditions tend to think of god not so much as a personal being, but as an impersonal force.

Thus, different religious traditions take the term “god” to refer to very different things. One might think that these different views are not incompatible— perhaps all of the gods of these different religions equally exist, so all of the religious traditions can be equally correct. However, that doesn’t work because each tradition typically claims that only its particular god exists (or that their god is the most powerful). So although there is a sense in which all of these different traditions believe in god, they do not all believe in the same god since they believe in different, incompatible gods. The Christian believes in the Christian (triune) god but disbelieves in all of the other gods (Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Greek, and so on). The Muslim believes in the Muslim god but not in any of the others. And so on for every religious tradition.

There is a popular atheistic argument that proceeds from this fact that each religious tradition disbelieves in the god of every other religious tradition. It’s called the “one god further” argument. Imagine a list of all the gods that humans have ever believed in. This list would include lots and lots of gods, including ancient Aztec gods, the gods of the Australian aborigines, the Greek gods, and the Christian god, to name just a few. Suppose you were to ask a Christian whether he believes in the gods on that list. He will say that he disbelieves in every single god on the list except one—the Christian god. So the Christian disbelieves in all of these other gods that other human beings have fervently believed in. Next you ask the Muslim the same question and he’ll give you a similar answer: he will disbelieve in every god on the list except one—the Muslim god. And so on and so forth for every other religion. The only difference between each of these different religious traditions and the atheist is that the atheist goes “one god further” than each of these other religions. So atheism isn’t that strange of a position at all. In fact, every religious tradition is itself atheistic with respect to every other religious tradition’s god. In other words, those religious traditions already acknowledge not only the plausibility but also the truth of the position that the atheist holds with respect to all gods since those different religious traditions hold this position with respect to almost all gods. Perhaps the atheist has the simpler explanation here.

However, suppose that we were not interested in whether the Christian god or the Muslim god or the Aztec god exists, but whether any god at all exists. It could turn out, for example, that none of the gods on our list of gods humans have believed in exist. And yet it might still be the case that some other god exists. For example, there could be a being that created the universe but that no religious tradition has ever conceptualized or worshipped. One way of thinking about the arguments for the existence of god that follow in this chapter is that they are aimed at establishing a much more general notion of “god,” one that is compatible with many different religious traditions, but doesn’t entail any one of them. Although the arguments that follow were developed mainly within the Abrahamic religious traditions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), they don’t necessarily establish (if sound) the existence of an Abrahamic god, but rather something much more general.

In the remainder of this chapter we will consider two different arguments for the existence of this more general notion of god: the teleological argument and the cosmological argument. In addition, we will consider two challenges to the existence of god: the problem of evil and the problem of religious diversity. The point of this chapter is not to convince you that god exists or doesn’t exist, but rather to consider some influential attempts to argue for one conclusion or the other. As always, these issues go much deeper than I can possibly introduce here. But the arguments presented here are a very good place to start.

The teleological argument

The teleological argument is an argument that moves from considerations about design in the natural world to the existence of a designer. (The word “telos” in Greek refers to the notion of a goal or purpose.) The basic idea behind the teleological argument is that if we admit that universe contains design (whether in particular objects, such as the eye, or in the organization of the whole earth or universe) then we must give an explanation of where that design comes from and the best explanation of where that design comes from is from a non-human designer. Below we will discuss a specific version of the teleological argument called the analogical teleological argument. The crux of this argument is an analogy between artifacts (objects made by human beings) and natural objects like the eye or the heart. The idea is that if we admit that the design of artifacts requires someone who designed them, then we must admit that design in natural objects (like the human eye) also requires someone who designed them. However, unlike the artifact, the designer of natural objects cannot be a human being, thus it must be some other non-human, intelligent designer.

Suppose while digging in the ground one day you found an old pocket watch. A question would naturally arise about where the watch came from in a very different way from the question of where, say, a rock or a clod of dirt come from. In the case of the rock, it would be plausible to say that it had just always been there, whereas in the case of the watch it doesn’t seem plausible to say that the watch had always been there. The difference between the rock and the watch is that the watch is an artifact—something that is made by humans rather than made by natural processes—whereas the rock isn’t. The watch has many different parts that have been arranged precisely and intentionally such that a certain goal or purpose can be achieved, namely so that by the steady movement of the hands on the watch face we are able to keep track of time.

Artifacts look different than natural objects. Artifacts often have an apparent structure and function to them that non-artifacts lack. Imagine, for example, that you are walking through the woods in the fall and see a bunch of leaves arranged on the ground according to color. The yellowish leaves are on one side of the arrangement and the reddish leaves are on the other side and the color of the leaves in the arrangement gradually shade-off from the yellow the red. Were you to encounter this arrangement, what would you think? Probably that some human being had intentionally arranged the leaves by color. Why?

Because there is an order, a pattern, a design whose best explanation seems to be in terms of someone’s goal or purpose rather than in terms of wind, rain, and other natural forces. A naturally occurring pile of leaves would not be arranged in this way. Rather the colors would tend to all be mixed together, with some leaves being right side up and other leaves being upside down. It would be extremely unlikely that nature (leaves falling randomly, wind, and so on) would produce an arrangement of leaves like that described above. The best explanation for the color-coded arrangement is that some person did it for some purpose (perhaps for aesthetic reasons). In contrast, we don’t need any such explanation for the random pile of leaves since nature produces such effects all the time.

The pocket watch (imagine a mechanical device, not a digital one) has a similar kind of design that makes the inference to a human designer irresistible. The watch has gears that turn one another and that ultimately turn the second, minute, and hour hands on the watch face. It has a tiny wheel that allows you to wind it up. It has markings on the watch face that allows you to precisely tell where the hands are on the watch face. All of these features are analogous to the leaves arranged according to color in the above example. They are features that exhibit design and that make the inference to a human designer feel irresistible and obvious in a way that the pebbles on the beach or the random pile of leaves isn’t.[2]

One of the most famous examples of the analogical teleological argument comes from William Paley who was an Anglican minister and theologian at Cambridge University in the late 18th century. The watch example discussed above derives from Paley. Paley argues that if it is obvious that the watch was designed then it is just as obvious that certain natural objects were designed. One of my favorite examples of Paley’s is one where he compares a telescope to an eye:

As far as the examination of the [telescope] goes, there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it. They are made upon the same principles, both being adjusted to the laws by which the transmission and refraction of rays of light are regulated. I speak not of the origin of the laws themselves; but such laws being fixed, the construction in both cases is adapted to them. For instance, these laws require, in order to produce the same effect, that the rays of light, in passing from water into the eye, should be refracted by a more convex surface, than when it passes out of air into the eye. Accordingly, we find that the eye of a fish, in that part of it called the crystalline lens, is much rounder than the eye of terrestrial animals. What plainer manifestation of design can there be than this difference? What could a mathematical instrument-maker have done, more, to show his knowledge of his principle, his application of that knowledge, his suiting of his means to his end; I will not say to display the compass, or excellence of his skill and art, for in these, all comparison is indecorous, but to testify counsel, choice, consideration, purpose? (Paley, Natural Theology, 1802)[3]

Paley is claiming the order and purpose observable in the telescope is analogous (the same in relevant respects) to the order and purpose is observable in natural objects, like eyes. If we find the inference to a designer irresistible in the case of the telescope, we should find it irresistible in the case of eyes (and a myriad of other natural objects that exhibit design), as well. The only difference is that whereas in the case of artifacts like watches, telescopes, and color-coded piles of leaves it is clear that humans could be the designers, in the case of natural objects like eyes, the designer could not be a human. Thus, in the case of natural objects, the designer would have to non-human. And what kind of thing might a non-human intelligent designer be (asks Paley with a twinkle in his eyes)?

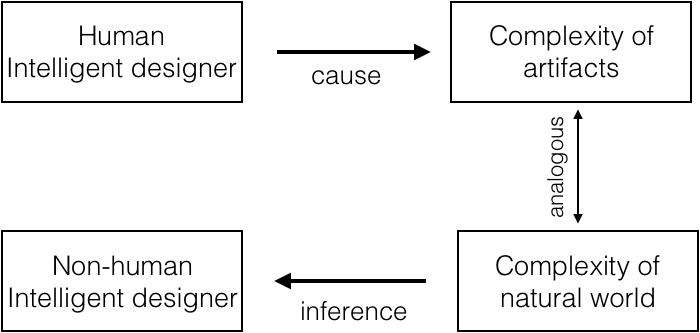

As noted, Paley’s argument is an analogical argument and the analogy explained in the following diagram.

The complexity of artifacts is analogous to the complexity observed in natural objects. Thus, because we know that artifacts are designed by human intelligent designers, it must follow that objects in the natural world are also designed, albeit by some non-human natural designer. Here is Paley’s reconstructed argument:

- The examples of complexity we observe in artifacts (for example, a watch, a telescope, a color-coded pile of leaves, and so on) are created by human intelligent designers

- We observe things of even more complexity in the natural world (for example, eyes, organisms, the universe itself)

- Like effects imply like causes

- Therefore, the cause of complexity in the natural world must a non-human intelligent designer of some sort (from 1-3)

Of course, Paley himself would like the ultimate conclusion to be that the god of Christianity exists. But I have suggested above that the best way of construing these arguments are for a much broader conclusion. The explicit conclusion of Paley’s is just that there exists some non-human intelligent designer. One might hope that this gets you at least in the range of something godlike. However, it doesn’t. Let’s consider some different possibilities of what could count as “an intelligent designer of some sort.”

Suppose that there is a civilization of hyper-intelligent Martians on some other planet in the universe. Suppose that this race of Martians created life on this planet as a kind of project (perhaps they’ve also done this on other planets in the universe that we don’t know about). The Martians could be the non-human intelligent designer(s) that the argument’s conclusion makes reference to. This seems a far cry from any notion of god. Rather, the Martians are just another race of intelligent beings in the universe that live and die and make mistakes; they are not gods. Although one might try to define them as gods, the Martians seem to fall short of what most religions intend when they venerate and worship god.

In 1859 Charles Darwin published his magisterial On the Origin of Species in which we put forward and meticulously documented the theory of natural selection. What Darwin showed (and what has since been confirmed as well as any scientific theory has been) is that order and complexity can emerge from unintelligent, mechanical processes. All that is needed is several conditions,

including a mechanism of inheritance that is almost, but not quite, perfect. That is, the mechanism needs to reproduce organisms that have the traits of the parent organisms in a way that is almost, but not quite, flawless. We now understand exactly what this mechanism is in a way that Darwin didn’t: it’s DNA, which Watson and Crick discovered the structure of in the 1950s. It sometimes happens that DNA does not perfectly replicate and when this happens a mutation occurs. Sometimes these mutations can have beneficial effects for an organism and when they do, those mutations tend to be passed on to further generations and in this way the mutation tends to spread through a population. For example, suppose a moth was always light colored but then something changed in the environment to make the moth’s environment darker colored. In this new environment, the light colored moth is more visible to predators and thus more likely to be eaten by them. However, suppose that a random mutation occurs in one of the moths to turn it from light-colored to dark- colored. In this new environment, the dark-colored moth will tend to be more successful than the light-colored moths (that is, it will tend not to get killed by predators as often as the light-colored moths). Because of how it enables the organisms that possess it to be successful, this new mutation that causes the dark coloring will tend to pass through a population.[4] In this way, species can change and, eventually, create new species. Darwin’s idea is that by this same kind of process, over long periods of time, speciation occurs. Ultimately we get organisms that are amazingly well designed to their environments—exactly the kind of design that so struck Paley. However, although there is a sense in which organisms are indeed designed by natural selection, this design is not “forward looking” or intelligent. Rather, species have the traits they have simply because of random mutation combined with the process of natural selection. But this “designer” doesn’t look at all like the non-human designer that Paley was intending. That is, natural selection doesn’t look anything like a god.

Let’s pause for a second to note an interesting connection between Paley and Darwin. Darwin actually had to read, and was much influenced by, Paley when he was a college student. Here’s Darwin from his autobiography:

Again in my last year I worked with some earnestness for my final degree of B.A., and brushed up my classics together with a little algebra and Euclid, which latter gave me much pleasure, as it did whilst at school. In order to pass the B.A. examination, it was, also, necessary to get up Paley’s ‘Evidences of Christianity,’ and his ‘Moral Philosophy.’ … The logic of this book and as I may add of his ‘Natural Theology’ gave me as much delight as did EuclidI did not at that time trouble myself about Paley’s premises; and taking these on trust I was charmed and convinced by the long line of argumentation. … The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man.[5]

Thus, the analogical teleological argument was delivered a huge blow by Darwin. The problem is that even if we agree that design implies a designer, it doesn’t follow that that designer is intelligent or a person or any of the attributes that the religious traditions give to god. Essentially what Darwin did was that he challenged premise 3 of Paley’s argument. His claim was that like effects do not always imply like causes and he showed that this was the case. When you think about it, premise 3 of the above argument seems to be the weakest. There are plenty of examples where two of the same types of things have very different causes. I’ll leave it to the reader to come up with examples.

So not only does the analogical teleological argument fail to establish any particular conception of god (which in any case isn’t best seen as its intention), it doesn’t even establish a broad conception of god. On the one hand, the Martians example shows that even if we accept the validity of the argument, the conclusion doesn’t establish that this non-human intelligent designer is godlike. On the other hand, natural selection shows that the whole analogy on which the argument is based is flawed since the existence of complexity and design does not establish that there was an intelligent designer. Natural selection is indeed a kind of designer, but it is not intelligent and does not seem to be in any kind of way godlike.

But this isn’t even the last of the problems that have been famously raised against the analogical teleological argument. We will close this section with one last famous problem that was raised by David Hume before Paley ever devised his argument. What Hume noticed is that if complexity establishes that something is designed and if the only thing that can explain design is a designer, then an infinite regress looms for the teleological argument. What Hume recognized was that an intelligent designer is itself a complex thing and thus would require explanation in terms of some other intelligent designer. But then the same point would apply to this new intelligent designer: it is itself a complex thing and thus would require explanation in terms of some further intelligent designer. Now you should see the problem: the premises of the argument lead to a paradox of an infinite number of different intelligent designers.[6] But presumably there can’t be an infinite number of different intelligent designers and in any case this seems to be at odds with what most religious traditions believe.

There are other teleological arguments besides the analogical argument. One that has been much discussed in recent years is called the fine-tuning argument. The fine-tuning argument focuses on the extremely narrow range of physical constants that make possible life as we know it. The idea is that given all the conditions that must simultaneously be in place in order for there to be life, it is extremely unlikely that these would have just occurred. Rather, God must have “fine-tuned” them so that the universe could support life—specifically, human life.

But what is meant by the claim that this universe—the one that supports life like ours—is highly improbable? If we are comparing one possible option with another, then each option (of the billions of different options) has an equally low probability. So our particular universe isn’t any more special than other possible universes in this sense. When we think of the probability of our particular universe, and saying that it is improbable, we note our particular case only because we have an interest in it. It is striking to us that we might not have existed because we can think of all the cases in which we wouldn’t have existed if something very small had been different. But from the point of view of the universe our human interests don’t matter. Rather, the universe cares just as much about the possibility in which humans exist as about all the other possibilities in which we don’t. They’re all equally probable from the perspective of the universe.

Furthermore, it doesn’t make sense to say that this universe is “more complex” than other possible universes because, again, complexity is something relative to our interests. We single out the various physical constants that are important from our perspective—that is, those that support our human existence.

Consider an analogy. What is the likelihood that you exist? Your individual existence is extremely improbable, yes, but this is only relative to your interest in existing. Your existence is just a likely (or unlikely) as anyone else’s; it isn’t any more or less probable than any other possible person that might have existed in your place. Any of the myriad possible (but not actual) individuals that might exist today have the same kind of objective probability of existing. Someone was going to exist, it just happened to be you. Yes, that was unlikely, but so was every other possibility. Nevertheless, one of the possibilities was going to take place, no matter what. We can dramatize the point by considering a coin- flipping tournament. How probable it is that I win 10 consecutive coin flips?

Not very likely, of course. But suppose we arrange an elimination tournament with 10 rounds (this will involve 1024 contestants). In that case, someone has to win and thus someone will win 10 consecutive coin flips. The winner will think they are special, but really someone had to win; it just happened to be them.

The improbability of their winning the tournament doesn’t require any fine- tuning![7] The same point applies to the existence of humans in the universe. Yes, it is unlikely that we exist, but so is every other possibility. It just happened to be us but that doesn’t make use special from the perspective of the universe. The actual universe containing human beings is just one of a myriad of different possible universes. Perhaps most of those other universes do not contain intelligent beings. If so, then although we are right to think that our existence is improbable, we are wrong to think that this requires a radically different kind of explanation—one involving fine-tuning. On the other hand, perhaps many of those other universes do contain life, including intelligent beings. If so, then our universe is not really that special at all (and thus our universe doesn’t require any kind of fine-tuning). Thus, regardless out how likely life is in other possible universes, it doesn’t seem to provide any reason to bring in any intelligent designers.

Study questions

- True or false: the teleological argument rests on an analogy between artifacts and natural objects.

- True or false: One of the premises of the teleological argument is that god is a loving and powerful being

- True or false: if there is a nonhuman intelligent creator of the world, then it follows that god exists.

- True or false: Darwin’s theory of natural selection can be seen as a challenge to the idea that “like causes imply like effects.”

- True or false: The analogical teleological argument doesn’t establish that the Christian god exists, but it does establish that some god or other exists.

- True or false: There is more than one version of the teleological argument besides the analogical version.

- True or false: One problem with the analogical teleological argument is that the intelligent designer would itself require an explanation in terms of another intelligent designer, and so on.

For deeper thought

- Sometimes one and the same outcome/effect can have radically different causes. For example, the human being playing chess and making decisions based on their conscious awareness vs. a computer playing chess using a series of algorithms. From the outside the behavior of the two things looks the same, but the cause is totally different (conscious thought vs. mindless algorithm). Come up with another example where one and the same thing have two radically different causes.

- One of the characters named Cleanthes in David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion makes the following rebuttal to the infinite regress objection: “You ask me, what is the cause of this cause? I know not; I care not; that concerns not me. I have found a Deity; and here I stop my enquiry. Let those go farther, who are wiser or more enterprising.” Essentially his response is that it doesn’t matter that there are further designers of the intelligent designer and that this doesn’t undermine the point that there is a god. Do you think this is a good response? Why or why not?

The cosmological argument

Whereas the teleological argument draws on specific, often scientific, details about natural objects on Earth, the cosmological argument proceeds from more abstract considerations about the nature of cause and effect in general and applies those considerations to questions about the origin of the universe. The cosmological argument is probably the oldest of the arguments for the existence of god since we can trace versions of it back as far as Aristotle (384- 322 BCE). Aristotle argued for the existence of an “unmoved mover” based on considerations about causation. If any thing that is in motion was caused by something else in motion, then if we were to trace those things in motion back in time and assuming the chain of causes/effects is not infinite, then it follows that there must have been some first thing that moved other things but that was not itself moved by any other thing. This is what Aristotle called the unmoved mover.

Like the teleological argument, there are a number of different versions of the cosmological argument. Islamic philosophers in the middle ages translated Aristotle, studied his arguments, and then developed different versions of the argument. The work of those Islamic philosophers influenced Jewish and Christian philosophers to come up with their own versions of the cosmological argument.[8] In this section we will consider just one version of the cosmological argument—one that comes from one of the most influential medieval philosophers: Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). Here is Aquinas in his own words (translated in English from the original Latin, of course):

The second way is from the nature of efficient cause. In the world of sensible things we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several or one only. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate, cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name God.[9]

Aquinas’s argument bears a striking similarity to Aristotle’s. Read carefully through Aquinas’s argument above and see if you can figure out the logic of the argument: what is the conclusion? What are the premises and how are they supposed to support the conclusion? Obviously the main conclusion that Aquinas is driving at is that God exists, which is what Aquinas is concluding in the last sentence. However, it is important to note that the conclusion that the argument most directly establishes is that there is a “first efficient cause.” He then goes onto assume that that first efficient cause is god. Aquinas doesn’t really give much of an argument for that assumption (that the first efficient cause is god) and so it is obviously the weakest part of the argument.

But let’s set that aside for now and look at the conclusion that he does provide an argument for. One of Aquinas’s premises is just that a thing cannot be the efficient cause of itself (see the third sentence of Aquinas’s argument above). All he means by “efficient cause” is just what we mean by “cause” (more or less).

Think of billiards balls knocking into each other: the first one bumps into the second and the second begins to move and then bumps into the third, and so on. That’s the kind of thing that Aquinas is talking about here. And his point is that a thing cannot cause itself because it is not possible for a thing to be prior to itself. Consider the billiards balls again: the second ball cannot be the cause of its own movement because the second ball’s movement required something else to be happening before it moved—in this case, the first ball’s movement. That is, it would have required the second ball to be moving before it was moving, which is not possible. This seems to be generally true of causes and effects: if A is the cause and B is the effect, then A must precede B in time. If A comes after B in time then A cannot be the cause of B. So, Aquinas’s first crucial premise is: it is not possible for something to cause itself.

The next crucial premise that Aquinas attempts to establish in the above paragraph is that it is not possible for the chain of causes/effects to go on to infinity. What he means is just that any actual series of causes and effects will not be infinitely long. Rather, it will terminate at some point—at the beginning. Aquinas’s reason for thinking that the chain of causes cannot be infinite is that if you were to remove the first cause then you’d have no other effects that follow. It might be helpful here to think of a line of dominoes: if you remove any of the dominoes from the chain, then the dominoes that follow will no longer be knocked over. Likewise, if you never knock over the first domino, then none of the others fall. Aquinas’s point is this: we can see that things are being caused right now in a myriad of different ways. Those things must have causes and those causes must themselves have causes, and so on. But that couldn’t be the case if there wasn’t a first cause. Aquinas’s crucial assumption seems to be that if a chain of causes were literally infinite then that is the same as removing the first cause. And as we have seen, if you remove the first cause (for example, you don’t knock over the first domino) then none of the other causes will occur, which means that the effect that we are observing in the world right now won’t occur either.

The only other premise that Aquinas is relying on in the above paragraph is the obvious one that there are things that are caused. This is obvious if we just observe the world around us. But Aquinas needs this premise because even if the above two crucial premises were true, it wouldn’t mean that there had to be an uncaused first cause. Often times a premise will be unstated in an argument because it is already obviously true and doesn’t need to be asserted. Other times the unstated premise is needed to make the argument work, but it is far from obviously true. I’ve denoted these unstated premises in the final reconstructed argument below as “missing premises.” Here, then, is Aquinas’s argument reconstructed with all the missing premises that are needed to make it valid:

- There exist things that are caused. [missing premise]

- It is not possible for something to cause itself.

- The chain of causes of any event cannot be infinite.

- Therefore, there is a cause of the existence of some things which is itself uncaused. [from 1-3]

- If there is a cause of the existence of some things which is itself uncaused, then God exists. [missing premise]

- Therefore, God exists. [from 4-5]

The logic of this argument is airtight, it seems. That is, if we assume the truth of the premises, the conclusion must be true. That is what it means for an argument to be valid. However, even if the argument is valid it might have a false premise. It seems there are two premises here to challenge: premise 3 and premise 5. Let’s consider each premise in turn.

Premise 3 is essentially saying that the universe cannot be infinitely old. But is this true? Why couldn’t the universe (and hence the chain of causes) be infinite? This is actually a question that physicists have pondered and investigated. The standard answer the physicists give is that the universe is not infinite but had a beginning—something they refer to as the Big Bang. If we calculate backwards based on an estimate about the size of the universe and the rate at which the universe is expanding, we can come up with a surprisingly precise number: 13.7 billion years. That is the age of the universe according to physicists. But does that settle the matter? Does this consensus within physics show that Aquinas was correct and that the universe is not infinitely old?

Here is one reason to think not. Consider what happened before the Big Bang. Physicists will often say that this is not a question that makes sense to ask from the perspective of physics since space-time came into existence with the Big Bang. However, that raises the obvious question of whether physics settles all of the questions it makes sense to ask about the origin of the universe? Even if physics can’t comment on what took place before the Big Bang, we can still ask the question of whether there was something before it. In any case, logically it seems that there could have been a previous universe before this one. It is hard to see how one could rule out that possibility. But that is exactly what Aquinas is trying to do. Is his argument successful? Is it true that if there wasn’t a first cause then there wouldn’t be any present causes (which is clearly not the case)? Here is a reason to think not. Although it is mind-boggling to consider the possibility that the universe does not have a beginning, this possibility wouldn’t mean that there couldn’t be present causes. Aquinas seems to be assuming something like that one could never travel through an infinite series of causes in order to arrive at the current causes that we observe. But this seems to assume that we need to be able to go back all the way in time to trace this series of causes leading up to the current effect that we are observing. Why make that assumption? Why not just say that there was always a previous cause? We can go back as far as we’d like and we will find an uninterrupted chain of causes leading up to the present. Why does it matter that we can’t go all the way back in time? In fact, if the universe really is infinite—if there was another universe before the Big Bang and so on for an infinite amount of “universes”—then the “chain” of causes could indeed be infinite. Saying that the chain of causes is infinite is not the same as removing the first cause in a known series of causes.

Rather, it is just making that series infinitely long. Because Aquinas thinks that an infinite chain is just like removing the first cause in a known sequence of causes, he thinks it is contradictory. But if we challenge that assumption, then Aquinas’s third premise is false and the argument would fail.

The other obvious premise to challenge is premise 5. This is the missing premise that would be needed in order to get to the conclusion that god exists. As I said above, Aquinas doesn’t really seem to argue for the main conclusion, but if he were to do so, he’d have to defend something like premise 5. That is, he’d have to show us why the existence of an uncaused cause is the same thing as god. But it seems that there are plenty of counterexamples to that. For example, suppose that the universe is actually finite and that there aren’t multiple universes that have existed before this one. In that case, the Big Bang itself (or “quantum fluctuations” or whatever physicists determine it to be) would be an uncaused cause. But the Big Bang doesn’t seem to be the kind of thing that religions worship as god. It certainly isn’t the kind of thing that Christianity considers to be god. So there’s a huge leap in logic there that is totally unsupported by any evidence.

Let’s pause for a moment to make an important point about the preceding two arguments (teleological argument, cosmological argument). What these arguments purport to do is to establish the existence of god based on neutral evidence. It seems that neither one of the arguments we’ve considered does that. For example, Aquinas’s argument at best only gets us to an uncaused first cause—Aristotle’s unmoved mover. Aquinas thinks it plausible to say that this thing is god, but we have seen that that inference doesn’t follow. If the Big Bang (or quantum fluctuations) were the uncaused first cause then this isn’t anything close to traditional religious concepts of god. But one might plausibly claim a much weaker conclusion instead. Suppose we grant that the cosmological argument establishes that there is an uncaused first cause (and the teleological argument that there is a non-human designer). If one is already religious and believes in a god then they might plausibly say that the best explanation for these two things—the thing that best answers to those descriptions (uncaused cause, non-human designer)—is god. But that explanation would already assume the existence of god as the thing doing the explaining (explanandum). The traditional point of these arguments is to establish the existence of god, not to assume it. Nevertheless, treating god as the best explanation of these purported facts would be a good move for the theist to take here. The question then becomes whether or not the theist’s explanation (that is, god) is a better explanation than the scientific explanations (natural selection, quantum fluctuations/Big Bang). This opens up a rather deep and important question—the relationship between scientific and religious explanations—that we won’t broach here.

Before leaving this section, consider the following question: Does logic force us to admit that there must have been a cause of the Big Bang? A theist might claim that it does. After all, it seems that something cannot come from nothing. The theist might say that even if the Big Bang is the cause of the universe, god is nevertheless the cause of the Big Bang, making god the ultimate cause. Is the theist’s position the more rational one here? It might seem so. After all, it feels incomplete to just say that the universe sprang into existence for no reason and without any cause. God as an explanation seems to give satisfying resolution.

However, on second though, is it really a satisfying resolution? Isn’t the theist just inheriting the same problem: that of admitting that there is something that has no cause? What caused god, after all? If the theist’s answer is (as it seems it must be) “nothing,” then it seems that the theist is in no better place rationally than the atheist is.

The cosmological argument raises some of the deepest questions humans can ask: where did everything come from? Why is there something rather than nothing? Has the universe always existed or did it come to exist and if so, how? When it comes to explaining the origin of the universe it seems that any position we take will involve embracing things that it is difficult to imagine could be true. Suppose we say that the universe is infinite and so there was no first cause. This could be true, but it is a hard thing for our human minds to understand.

Suppose, on the other hand, that there was a beginning. In that case it seems that there will have to be some uncaused cause. Whatever you call that thing, whether god or quantum fluctuations, the human mind balks at the very thought of an uncaused cause. Thus, it seems that everyone is, in a certain respect, in the same boat regarding explaining the universe: however you proceed, you’re going to have to accept something that seems false or paradoxical.

Study questions

- True or false: The cosmological argument attempts to establish the existence of god based on considerations about the nature of causes/effects.

- True or false: The cosmological argument has roots in ancient Greek philosophers.

- True or false: One of the premises of Aquinas’ argument is that nothing can cause itself.

- True or false: One assumption that Aquinas’ argument relies upon is that the existence of an uncaused first cause would mean that god exists.

- True or false: If it is scientifically true that the universe had a beginning (such as the Big Bang), then this undermines Aquinas’ argument.

- True or false: Aquinas’ argument proves that if there is an uncaused cause, then god exists.

- True or false: Regarding explaining the origin of the universe, the theist is in a stronger position than the atheist.

- True or false: The original intention of Aquinas’ cosmological argument was to provide neutral evidence that would establish to anyone that god exists.

- True or false: The claim that god provides the best explanation for the cause of the universe is a stronger claim than the claim that considerations about the cause of the universe proves that god exists.

For deeper thought

- What is one reason for thinking that it is not impossible for the chain of causes/effects to be infinite?

- What is the difference between saying that god best explains the existence of the universe and saying that the existence of the universe proves that god exists?

- What difficult claim must someone who is defending an infinite universe accept? What difficult claim must someone who is defending a finite universe (with a first cause) accept? Which claim do you think is less probable?

- Suppose that someone claimed that there must be a cause of the Big Bang since the Big Bang cannot have just come from nothing (and nothing comes from nothing)? How might one respond to this claim logically? (Hint: Is there any inconsistency in invoking the “nothing comes from nothing” principle and also claiming that nothing caused god?)

The problem of evil

The foregoing sections have considered arguments that attempt to establish that there is a god, but there are also arguments that attempt to establish that god doesn’t exist. One ingenious attempt to do this is the problem of evil.

Many religious traditions (including all the “Abrahamic” traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) conceive of god as a being who is both omnipotent (all- powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-good or all-loving). But given that it seems that really horrible, evil things exist in the world—a world that was created and designed by god—it is hard to see how god could be both loving and all- powerful at the same time. Rather, it seems that given the existence of evil in the world, either god isn’t all-powerful or god isn’t all-good. This is what is called the logical problem of evil. The “logical” just refers to the fact that the following three statements are logically inconsistent (that is, they cannot all simultaneously be true):

- God is omnipotent

- God is omnibenevolent

- Evil exists

David Hume captures the essence of the logical problem of evil succinctly when in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion the character Philo says,

“Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? when then is evil?”xxxxx

If we assume that god is all-powerful, then god would be able to do anything, including eliminate any evil and suffering from the world. The fact that evil exists, would seem to entail that god is not all-loving or good. On the other hand, if we assume that god is all-loving then god would never want there to be things like needless suffering in the world. But given that there does seem to be needless suffering, that would mean that although god wants there to be no suffering, he actually can’t control the fact that there is needless suffering. But if god wants to but can’t eliminate needless suffering, then god is not all-powerful. Thus, the problem is that A, B and C (above) cannot all be true. If we assume A and C are true, then B is false. If we assume B and C are true, and A is false.

There’s another option, however. Perhaps A and B are both true but C is false— that is, perhaps there isn’t any evil in the world. This of course should raise the question of what we mean by “evil.” For our purposes, let’s define evil as the existence of needless suffering—suffering that doesn’t seem to serve any purpose. Does it make sense to deny that evil exists in this sense? Let me give you two examples to consider. Consider genetic diseases like “Harlequin’s Ichthyosis” where a person grows too much skin at too fast a rate which ultimately kills the infant typically within a matter of a few months. That is just one rare disease, but there are many diseases that cause a lot of suffering for the people who have them. Here’s another example of a very different kind of evil. In 1984 Josef Fritzl asked his 18-year old daughter to help him carry a door into the basement of their home and then sealed her shut inside of it and then filed a missing persons report, claiming his daughter had disappeared. He proceeded to keep her locked as a prisoner in the basement for 24 years and fathered 7 children with her, all the while living out his life with his wife upstairs and her knowing nothing of what was happening. These two very different cases represent two very different kinds of evil: natural evil and moral evil.

Whereas moral evil concerns suffering that results from the actions of human agents (like Josef Fritzl or Adolf Hitler), natural evil concerns suffering that is not the result of human actions—things like cancer, forest fires, tsunamis, and so on. This distinction will be important in considering responses to the problem of evil below.

Responses to the logical problem of evil

There are basically two responses to the logical problem of evil: 1) deny that evil exists, 2) claim that the inconsistency is only apparent. Pursuing the first path seems a hard pill to swallow. The parent whose child was born with a rare genetic disease that causes their child much suffering won’t be swayed by the claim that that suffering isn’t really a bad thing. The suffering all around us immense, even if we don’t always know about it. From the suffering of the victims of all kinds of abuse, to the suffering of children who die each day from curable illnesses, to the suffering of individuals who have been hit by natural disasters—all of these kinds of suffering are bad and the world would be a better one if there weren’t so much of this suffering. That is in fact why so many people spend their lives trying to alleviate this suffering. It is hard to deny that the world would be better if it didn’t contain the suffering it does.

The other response is the much more common one and that is simply to deny that it is inconsistent for there to be a omnipotent, omnibenevolent god, on the one hand, and evil in the world, on the other. A common way of showing that statements are not really inconsistent is by adding a further statement that explicitly resolves the inconsistency. Here is an example of that using a case that has nothing to do with the problem of evil. Consider the following two statements:

- Bob is the tallest human being ever to have lived

- Sherman is taller than Bob

It looks like those two statements are inconsistent: if Bob is the tallest then Sherman cannot be taller than Bob. However, suppose we added the following statement:

- Sherman is not a human being

By adding that statement we explicitly resolve any apparent inconsistency. If Sherman is a tree, for example, then it can both be true that Bob is the tallest human being and also that Sherman is taller than Bob. Can we do something similar with the problem of evil? The former University of Notre Dame professor of philosophy, Alvin Plantinga, has suggested that we can and his idea is basically this:

- God is omnipotent

- God is omnibenevolent

- Evil exists

- God created a world containing evil and had a good reason for doing so

Plantinga’s point is that if D is true, then there is no logical inconsistency between A-C. Of course, this raises the question of whether D is true and Plantinga and other philosophers have argued that it is. The most common way of defending D is by presenting a version of what has become known as the free will defense. The basic idea behind the free will defense is that there is some greater good that cannot have been achieved without god allowing for there to be some evil. That greater good is moral goodness. A world without moral goodness, where people willfully undertake moral actions and develop their moral character is a better world, all things considered, than a world in which there is no moral goodness. But one of the things that is logically required for

moral goodness to exist is the possibility of human freedom—that is, human must have the choice to make either good or bad decisions. Consider: if humans did not have the capacity to make morally wrong decisions, then could we really praise them for being morally good? The crucial claim of the free will defense is that without the possibility of being able to make morally wrong decisions, moral goodness cannot exist. That’s because moral goodness cannot exist without genuine choice, including the option of being able to act/choose the morally wrong thing. So the idea is that god created human with free will so that they would be able to develop and exhibit moral goodness. However, given that humans have free will, they will sometimes make the wrong choice and thus bring evil (unnecessary suffering) into the world. But is a world with moral goodness really better than a world with no unnecessary suffering? The theist will try to argue that it is by having us consider what a world would be like without free will. God could have created a world containing creatures who were essentially robots who could only do the right thing—creatures who were programmed such that they were incapable of ever do anything that is morally wrong. This would be a world without evil, but it would seem to be lacking something important from a world in which the creatures could willfully choose to do good (when they had the option of doing bad). Thus, in order to bring about a better world containing moral goodness, god created beings with free will who could also willfully choose evil over good.

There are a number of things that one could respond to this argument, but let’s just consider one important thing before moving on. The free will defense only applies to explaining why there are certain kinds of evil—what we have above called “moral evil.” The free will defense does give us any reason for why there would be “natural evil” since human free will is in no way involved in the suffering that results from things like Harlequin’s Ichthyosis or a tsunami. In fact, there’s a whole natural world of suffering that exists quite independently of the realm of human actions. Consider, for example, predation in the animal kingdom. There is immense suffering within the natural world and this is something that religious people have long been aware of since it sits oddly with the idea of a loving creator. Why would a loving creator god create a world predicated on suffering and death? The study of biology reveals that evolution depends on death in order for species to evolve, but even if that it so, why need there be so much suffering and predation along the way (and for that matter why need there be evolution at all)? Presumably the gazelle doesn’t enjoy being eaten alive by the lions. The prophet Isaiah seemed to be aware of this when he envisioned a world in which there was no longer any predation—a more perfect world:

- The wolf shall dwell with the lamb,

- and the leopard shall lie down with the young goat,

- and the calf and the lion and the fattened calf together;

- and a little child shall lead them.

- The cow and the bear shall graze;

- their young shall lie down together;

- and the lion shall eat straw like the ox.[10]

The question is: why wouldn’t a loving, all-powerful god have created such a world in the first place? The free will defense doesn’t provide any answer to this question. It only gives a good reason for why god would allow moral evil, but does not provide any answer to why god allows natural evil.[11]

Study questions

- True or false: If we reject the idea that god is omnipotent then there is no logical problem of evil.

- True or false: The logical problem of evil is that there are three statements that it seems a theist must believe but that those statements are mutually inconsistent.

- True or false: By “evil” what is meant is unnecessary suffering.

- True or false: There is no important philosophical difference between natural evil and moral evil.

- True or false: A good example of moral evil would be a lion eating a gazelle alive.

- True or false: The free will defense is a good response to the problem of natural evil.

- True or false: Josef Fritzl is a good example of moral evil.

- True or false: Harlequin’s Ichthyosis is a good example of moral evil.

For deeper thought

- According to the free will defense, what is the greater good that justifies why god allows evil in the world? Do you think that this really is a greater good? Why or why not?

- Can you think of a good reason why god would allow/create natural evil?

- Consider a young fawn that is burned in a forest fire and lies suffering for days until it finally dies. Presumably such things have happened many times in the history of the world (even if no one knew about it). Does the existence of events such as this pose a challenge for the existence of an all-powerful, loving god? Why or why not?

- Consider a theist who responds to the problem of evil as follows: “God created/allowed evil in the world so that human beings would be able to work alongside god—a cooperative venture—to make the world a better place.” Do you think this is a good response to the problem of evil? Why or why not?

The problem of religious diversity

Whereas the problem of evil is a metaphysical challenge to the existence of god, the problem of religious diversity is an epistemic challenge to the existence of god. Roughly, metaphysics concerns what exists and what is true about the world whereas epistemology concerns our reasons or justification for believing something to be true. Sometimes there are situations where x could be true but that we could never know that it is true. For example, in physics there is a concept of things that are within our “light cone” which is basically the idea of things that we could physically access by travelling at the speed of light.

However, there are also things outside our light cone because those things are travelling away from us at faster than the speed of light. Hence it is not physically possible to access those things (not even with technology). Now consider the idea that there may be life other places within the universe but that is not within our light cone. We cannot rule out the existence of such life (that is, we cannot rule it out metaphysically) but we could never know that there is such life. Thus the possibility that there is life outside our light cone presents an epistemic problem, not a metaphysical one. The problem of evil is a metaphysical challenge because it claims that it is not possible for an omnipotent, all-loving god to exists (given evil). In contrast, as we will see, the problem of religious diversity presents an epistemic challenge to believing in a specific version of god within a specific religious tradition.

The problem of religious diversity asks us to consider religious believers from different traditions who believe in different gods and have different associated religious beliefs. For example, Christians believe that god is a Trinity (three persons but also, mysteriously, only one being) whereas Muslims believe that god is a unity and find the Trinity belief heretical. Judaism, in contrast, does not take Jesus to be divine, although they do take him to have been an important rabbi. Islam takes Jesus to be an important prophet but, unlike Christians, do not believe that Jesus was god or that his message was god’s most important prophet. Instead, Islam takes Muhammad to be god’s most important prophet. If we were to bring in non-Abrahamic religions, the conception of god would begin to diverge even more radically. All of these different religious traditions believe that their tradition is correct and this entails that the others are mistaken somehow. It is this fact that creates the epistemic problem, however. For consider a religious believer from a different tradition. For example, if you are a Christian, consider a Muslim who is just as intelligent, just as well-informed, just as devout as you are. Further, the Muslim has her own religious experiences,

draws on her own religious traditions, including her own religious texts and authorities. The Muslim, of course, believes that her tradition is the correct one just as much as you believe that your religious tradition is the correct one. Even if you are polite to each other about such things (as you should be), you probably still hold this belief and don’t explicitly express it to each other.

Nonetheless, the belief is there. But consider the kind of position these religious believers are in by claiming that the other is fundamentally mistaken about some important religious truth. You would have to be claiming that someone who has is in a very similar epistemic situation to you is actually fundamentally mistaken! Should this not raise the question of whether you are fundamentally mistaken if they are? Consider the tension of the Christian’s position:

I accept that my Muslim friend is just as intelligent and well-informed as I am and that they have their own religious tradition and religious experiences that they have come to trust just like I have and yet my beliefs are the correct ones and theirs are incorrect.

It seems that this recognition should occasion some doubt about the veracity of our own beliefs. In short, if the Christian accepts that a Muslim could have all the same kinds of evidence that they themselves do (religious experiences, religious traditions, religious texts, and so on) and yet that the Muslim is profoundly mistaken in their religious beliefs, then this admission should raise a question about the status of the Christian’s own beliefs. If my friend can have all the same kinds of evidence that I do and yet be profoundly mistaken, then perhaps I am mistaken too! Thus, the crux of the problem of religious diversity is that in admitting there are well-informed, reasonable, and devout believers within different religious traditions we thereby undercut our own epistemic position. That is, we acknowledge that possibility that we, too, are profoundly mistaken. And that recognition should make us much less certain that our beliefs are correct.

Responses to the problem of religious diversity

There are generally three different responses to the problem of religious diversity: religious pluralism, agnosticism/atheism, and religious exclusivism. Religious pluralism involves jettisoning specific religious beliefs attached to specific religious traditions and upholding a more general view of god that isn’t specific to any religious tradition (or at least that incorporates all the consistent parts of the different religions). For example, the Christian, were she to become a pluralist, would have to renounce the beliefs that Jesus was literally god, that there is a heaven an hell, that god is a Trinity, that the Bible (specifically the New Testament) is the unique revelation of god to the world, and so on. A well- known proponent of this kind of view was John Hick.[12] The pluralist hopes that by moving to a more generalized conception of a transcendent being, she can avoid the problems that attach to making the more specific claims of the different religious traditions. It is often objected to this view that it collapses into a kind of agnosticism, according to which we can’t really know anything at all about the supposed deity. Agnosticism and atheism involve jettisoning any belief in a god, finding it more plausible that we are all fundamentally mistaken about believing that there is any kind of god or supernatural being. Finally, religious exclusivism involves doubling down one one’s specific religious beliefs by claiming that there is some good reason for the religious believer to hold on to their specific beliefs. It is important to recognize two very different versions of religious exclusivism. On the one hand, one might claim that there are pragmatic reasons to hold onto one’s religious tradition. For example, if all of your family and friends are Christians and all of your social life revolves around that community and if becoming an atheist would alienate you from that community, then it would make sense to just remain a Christian rather than become an atheist. However, one should see that this kind of pragmatic reasoning doesn’t bear at all on what we might call one’s epistemic reasons.

Epistemic reasons concern evidence that something is true and it is clear that pragmatic reasons only involve what makes it easier for us to attain our goals. (Here’s a quick example to illustrate the difference. Consider a mother whose husband and father of her young children has died in some ignoble way, say as a result of erotic asphyxiation. The mother has a very good pragmatic reason to not tell her children the truth about the death of their father because of the way this would adversely affect her children’s wellbeing. But this pragmatic reason has nothing to do with what the evidence or truth actually is. Given her goal to protect her children, she lies to them. She has a good pragmatic reason to say, for example, that their father died by falling down the stairs but no epistemic reason for believing this.)

Another version of religious exclusivism says that there are epistemic reasons for a religious believer to maintain their specific religious beliefs/tradition. Well- known proponents of this view in recent years include William Alston and Alvin Plantinga (mentioned earlier). However, it is beyond the scope of this introductory chapter to engage these fascinating attempts to safeguard the epistemology of traditional religious beliefs (in this case, Christian beliefs).

Study questions

- True or false: Metaphysics concerns what we have reason or justification for believing to be true.

- True or false: Epistemology concerns what exists or what is true about the world.

- True or false: The problem of religious diversity is an epistemic challenge to religious beliefs.

- True or false: The problem of religious diversity assumes that there are intelligent, devout, well-informed persons within religious faiths other than our own.

- True or false: One objection to religious pluralism is that it collapses into agnosticism.

- True or false: pragmatic reasons and epistemic reasons are the same thing according to the religious exclusivist.

- True or false: The religious exclusivist claims that only one religion is correct.

For deeper thought

- Would someone who believed in a very general, non-specific “higher being” face the problem of religious diversity? Why or why not?

- Does religious pluralism really avoid the problem of religious diversity? Suppose she finds a devout Christian who is equally intelligent and equally as well-informed as she is. Should this undermine her confidence in her religious pluralism? Why or why not?

- Suppose that believing there is no god makes Mark very unhappy. His priest tells him that this gives him a good reason to try believing in god. Is the priest correct that this gives Mark a good reason to believe in god? Explain.

- One argument for atheist is that it is a simpler explanation of the fact that different religions disagree about the nature of god. Whereas the religions maintain that there is a god, but disagree about the nature of god, atheists maintain that the simplest explanation of the disagreement is that there is no god and humans are simply projecting these beliefs onto the world (Freud’s explanation of religion is similar to this). What do you think about this explanation of religious disagreement?

- Throughout this chapter the uncapitalized term, “god,” will be used to specify the generic concept of a higher being, irrespective of religion. In contrast, since specific deities are proper names, those will be capitalized (for example, Zeus, the Trinity, Yahew). Many religious have both generic terms for a deity and specific terms for specific deities. For example, the Hebrew word, Elohim, is a generic term for god, as is the Muslim term, Allah. (For this reason, Christians in Arabic-speaking countries refer to god as Allah, even though they are Christians, not Muslims.) In contrast, the Hebrew term Yaweh is a proper name that refers to a specific god. You can think of this distinction as analogous to the distinction between a car and Chevrolet. The term “car” is not capitalized but the proper name “Chevrolet” is. ↵

- Of course, it could have been the case that a person made the random pile of leaves and the assortment of pebbles on the beach, as well. However, although this could be the case, it also needn’t be. In contrast, in the case of the watch and the color-coded pile of leaves, we really can’t give a plausible explanation without invoking some human designer since those things don’t just randomly assemble themselves without the intervention of a human being. ↵

- http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=A142&pageseq=1&viewtype=text ↵

- This example is actually not made up, but real. You can read about it here: http://www.mothscount.org/text/63/peppered_moth_and_natural_selection.html ↵

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2010/2010-h/2010-h.htm ↵

- In Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779), the character Philo says, “How therefore shall we satisfy ourselves concerning the cause of that being whom you suppose the author of nature, or, according to your system of anthropomorphism, the ideal world, into which you trace the material? Have we not the same reason to trace that ideal world into another ideal world, or new intelligent principle? But if we stop, and go no farther; why go so far? Why not stop at the material world? How can we satisfy ourselves without going on in infinitum? And, after all, what satisfaction is there in that infinite progression?” The character Cleanthes responds to Philo: “You ask me, what is the cause of this cause? I know not; I care not; that concerns not me. I have found a Deity; and here I stop my enquiry. Let those go farther, who are wiser or more enterprising.” https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4583/4583-h/4583-h.htm ↵

- This example comes from Daniel Dennett’s 1995 book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (Simon and Shuster), pp. 53-56. ↵

- See Peter Adamson, Philosophy in the Islamic World: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2015. ↵

- This passage is from Aquinas’s Summa Theologica, which you can find online here: http://www.newadvent.org/summa/1002.htm ↵

- https://biblehub.com/esv/isaiah/11.htm ↵

- The reader may wonder about the following kind of common response that theists give: “God has reason for allowing natural evil but human cannot understand it.” The theist is entitled to Philosophy of Religion 138 give us a response and that may make a lot of theological sense from within their worldview. However, it seems that as soon as one gives this response, they have essentially given up on the project of offering reasons for their religious beliefs. I’m not saying that that isn’t a legitimate thing that the theist could do (indeed, the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard is famous for defending a kind of view like this—what philosophers call “fideism.” Rather, I’m noting that this response marks the theist refusing to engage in offering reasons for her beliefs. ↵

- https://www.iep.utm.edu/hick/ ↵