Chapter 15: The Bureaucracy

Toward a Merit-Based Civil Service

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how the creation of the Civil Service Commission transformed the spoils system of the nineteenth century into a merit-based system of civil service

- Understand how carefully regulated hiring and pay practices helps to maintain a merit-based civil service

While the federal bureaucracy grew by leaps and bounds during the twentieth century, it also underwent a very different evolution. Beginning with the Pendleton Act in the 1880s, the bureaucracy shifted away from the spoils system toward a merit system. The distinction between these two forms of bureaucracy is crucial. The evolution toward a civil service in the United States had important functional consequences. Today the United States has a civil service that carefully regulates hiring practices and pay to create an environment in which, it is hoped, the best people to fulfill each civil service responsibility are the same people hired to fill those positions.

THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

The Pendleton Act of 1883 was not merely an important piece of reform legislation; it also established the foundations for the merit-based system that emerged in the decades that followed. It accomplished this through a number of important changes, although three elements stand out as especially significant. First, the law attempted to reduce the impact of politics on the civil service sector by making it illegal to fire or otherwise punish government workers for strictly political reasons. Second, the law raised the qualifications for employment in civil service positions by requiring applicants to pass exams designed to test their competence in a number of important skill and knowledge areas. Third, it allowed for the creation of the United States Civil Service Commission (CSC), which was charged with enforcing the elements of the law.[1]

The CSC, as created by the Pendleton Act, was to be made up of three commissioners, only two of whom could be from the same political party. These commissioners were given the responsibility of developing and applying the competitive examinations for civil service positions, ensuring that the civil service appointments were apportioned among the several states based on population, and seeing to it that no person in the public service is obligated to contribute to any political cause. The CSC was also charged with ensuring that all civil servants wait for a probationary period before being appointed and that no appointee uses their official authority to affect political changes either through coercion or influence. Both Congress and the president oversaw the CSC by requiring the commission to supply an annual report on its activities first to the president and then to Congress.

In 1883, civil servants under the control of the commission amounted to about 10 percent of the entire government workforce. However, over the next few decades, this percentage increased dramatically. The effects on the government itself of both the law and the increase in the size of the civil service were huge. Presidents and representatives were no longer spending their days doling out or terminating appointments. Consequently, the many members of the civil service could no longer count on their political patrons for job security. Of course, job security was never guaranteed before the Pendleton Act because all positions were subject to the rise and fall of political parties. However, with civil service appointments no longer tied to partisan success, bureaucrats began to look to each other in order to create the job security the previous system had lacked. One of the most important ways they did this was by creating civil service organizations such as the National Association of All Civil Service Employees, formed in 1896. This organization worked to further civil service reform, especially in the area most important to civil service professionals: ensuring greater job security and maintaining the distance between themselves and the political parties that once controlled them.[2]

Over the next few decades, civil servants gravitated to labor unions in much the same way that employees in the private sector did. Through the power of their collective voices amplified by their union representatives, they were able to achieve political influence. The growth of federal labor unions accelerated after the Lloyd–La Follette Act of 1912, which removed many of the penalties civil servants faced when joining a union. As the size of the federal government and its bureaucracy grew following the Great Depression and the Roosevelt reforms, many became increasingly concerned that the Pendleton Act prohibitions on political activities by civil servants were no longer strong enough. As a result of these mounting concerns, Congress passed the Hatch Act of 1939—or the Political Activities Act. The main provision of this legislation prohibits bureaucrats from actively engaging in political campaigns and from using their federal authority via bureaucratic rank to influence the outcomes of nominations and elections.

Despite the efforts throughout the 1930s to build stronger walls of separation between the civil service bureaucrats and the political system that surrounds them, many citizens continued to grow skeptical of the growing bureaucracy. These concerns reached a high point in the late 1970s as the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal prompted the public to a fever pitch of skepticism about government itself. Congress and the president responded with the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, which abolished the Civil Service Commission. In its place, the law created two new federal agencies: the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). The OPM has responsibility for recruiting, interviewing, and testing potential government employees in order to choose those who should be hired. The MSPB is responsible for investigating charges of agency wrongdoing and hearing appeals when corrective actions are ordered. Together these new federal agencies were intended to correct perceived and real problems with the merit system, protect employees from managerial abuse, and generally make the bureaucracy more efficient.[3]

MERIT-BASED SELECTION

The general trend from the 1880s to today has been toward a civil service system that is increasingly based on merit (Figure 15.6). In this system, the large majority of jobs in individual bureaucracies are tied to the needs of the organization rather than to the political needs of the party bosses or political leaders. This purpose is reflected in the way civil service positions are advertised. A general civil service position announcement will describe the government agency or office seeking an employee, an explanation of what the agency or office does, an explanation of what the position requires, and a list of the knowledge, skills, and abilities, commonly referred to as KSAs, deemed especially important for fulfilling the role. A budget analyst position, for example, would include KSAs such as experience with automated financial systems, knowledge of budgetary regulations and policies, the ability to communicate orally, and demonstrated skills in budget administration, planning, and formulation. The merit system requires that a person be evaluated based on ability to demonstrate KSAs that match those described or better. The individual who is hired should have better KSAs than the other applicants.

Many years ago, the merit system would have required all applicants to also test well on a civil service exam, as was stipulated by the Pendleton Act. This mandatory testing has since been abandoned, and now approximately eighty-five percent of all federal government jobs are filled through an examination of the applicant’s education, background, knowledge, skills, and abilities.[4] That would suggest that some 20 percent are filled through appointment and patronage. Among the first group, those hired based on merit, a small percentage still require that applicants take one of the several civil service exams. These are sometimes positions that require applicants to demonstrate broad critical thinking skills, such as foreign service jobs. More often these exams are required for positions demanding specific or technical knowledge, such as customs officials, air traffic controllers, and federal law enforcement officers. Additionally, new online tests are increasingly being used to screen the ever-growing pool of applicants.[5]

Civil service exams currently test for skills applicable to clerical workers, postal service workers, military personnel, health and social workers, and accounting and engineering employees among others. Applicants with the highest scores on these tests are most likely to be hired for the desired position. Like all organizations, bureaucracies must make thoughtful investments in human capital. And even after hiring people, they must continue to train and develop them to reap the investment they make during the hiring process.

GET CONNECTED!

A Career in Government: Competitive Service, Excepted Service, Senior Executive Service

One of the significant advantages of the enormous modern U.S. bureaucracy is that many citizens find employment there to be an important source of income and meaning in their lives. Job opportunities exist in a number of different fields, from foreign service with the State Department to information and record clerking at all levels. Each position requires specific background, education, experience, and skills.

There are three general categories of work in the federal government: competitive service, excepted service, and senior executive service. Competitive service positions are closely regulated by Congress through the Office of Personnel Management to ensure they are filled in a fair way and the best applicant gets the job (Figure 15.7). Qualifications for these jobs include work history, education, and grades on civil service exams. Federal jobs in the excepted service category are exempt from these hiring restrictions. Either these jobs require a far more rigorous hiring process, such as is the case at the Central Intelligence Agency, or they call for very specific skills, such as in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Excepted service jobs allow employers to set their own pay rates and requirements. Finally, senior executive service positions are filled by men and women who are able to demonstrate their experience in executive positions. These are leadership positions, and applicants must demonstrate certain executive core qualifications (ECQs). These qualifications are leading change, being results-driven, demonstrating business acumen, and building better coalitions.

What might be the practical consequences of having these different job categories? Can you think of some specific positions you are familiar with and the categories they might be in?

LINK TO LEARNING

Where once federal jobs would have been posted in post offices and newspapers, they are now posted online. The most common place aspiring civil servants look for jobs is on USAjobs.gov, a web-based platform offered by the Office of Personnel Management for agencies to find the right employees. Visit their website to see the types of jobs currently available in the U.S. bureaucracy.

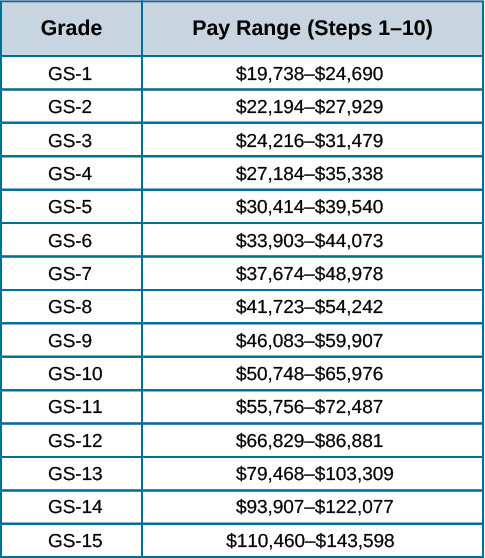

Civil servants receive pay based on the U.S. Federal General Schedule. A pay schedule is a chart that shows salary ranges for different levels (grades) of positions vertically and for different ranks (steps) of seniority horizontally. The Pendleton Act of 1883 allowed for this type of pay schedule, but the modern version of the schedule emerged in the 1940s and was refined in the 1990s. The modern General Schedule includes fifteen grades, each with ten steps (Figure 15.8). The grades reflect the different required competencies, education standards, skills, and experiences for the various civil service positions. Grades GS-1 and GS-2 require very little education, experience, and skills and pay little. Grades GS-3 through GS-7 and GS-8 through GS-12 require ascending levels of education and pay increasingly more. Grades GS-13 through GS-15 require specific, specialized experience and education, and these job levels pay the most. When hired into a position at a specific grade, employees are typically paid at the first step of that grade, the lowest allowable pay. Over time, assuming they receive satisfactory assessment ratings, they will progress through the various levels. Many careers allow for the civil servants to ascend through the grades of the specific career as well.[6]

The intention behind these hiring practices and structured pay systems is to create an environment in which those most likely to succeed are in fact those who are ultimately appointed. The systems almost naturally result in organizations composed of experts who dedicate their lives to their work and their agency. Equally important, however, are the drawbacks. The primary one is that permanent employees can become too independent of the elected leaders. While a degree of separation is intentional and desired, too much can result in bureaucracies that are insufficiently responsive to political change. Another downside is that the accepted expertise of individual bureaucrats can sometimes hide their own chauvinistic impulses. The merit system encouraged bureaucrats to turn to each other and their bureaucracies for support and stability. Severing the political ties common in the spoils system creates the potential for bureaucrats to steer actions toward their own preferences even if these contradict the designs of elected leaders.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 15.3 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- United States Civil Service Commission. 1974. Biography of an Ideal: a history of the federal civil service. Washington, D.C.: Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Civil Service Commission. 40–44 ↵

- Ronald N. Johnson and Gary D. Libecap. 1994. The Federal Civil Service System and the Problem of Bureaucracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press ↵

- Patricia W. Ingraham and Carolyn Ban. 1984. Legislating Bureaucratic Change : The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978. Albany: State University of New York Press ↵

- Dennis V. Damp. 2008. The Book of U.S. Government Jobs: Where They Are, What’s Available, & How to Get One. McKees Rocks, PA: Bookhaven Press, 30 ↵

- Lisa Rein, “For federal-worker hopefuls, the civil service exam is making a comeback,” Washington Post, 2 April 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/federal-eye/wp/2015/04/02/for-federal-worker-hopefuls-the-civil-service-exam-is-making-a-comeback/ ↵

- https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/general-schedule-qualification-policies/#url=General-Policies (May 16, 2016) ↵

a chart that shows salary ranges for different levels of positions vertically and for different ranks of seniority horizontally