Gloria Anzaldua: Decolonizing the Chicano Narrative

Megan Delvalle

Introduction:

Gloria Anzaldua (b. 1942- d. 2004) was a queer Chicana poet, writer, and feminist theorist whose work reflected her own life experiences as a Mexican American growing up in the American southwest. Her most notable work, “Borderlands, La Frontera/ The New Mestiza” explores the realities that one faces when existing, not only in a literal borderland, but also a cultural one. The legacy of colonialism transformed not only the physical landscape of the Southwest, but also the identities of the people that inhabited it. The annexation of this territory by the United States left many individuals to grapple with the reality that they were now considered immigrants in the lands they had occupied for generations. While Anzaldua’s writing stemmed from her own experiences growing up in Texas, the themes throughout resonate with the lived experiences of many Chicanos/as across the U.S. leading to the enduring influence and celebration of her work.

Themes:

- This portfolio aims to engage with Gloria Anzaldua’s writings from her book “The Borderlands, La Frontera/ The New Mestiza” to demonstrate how the themes of cultural identity and imaged communities interweave in an attempt to decolonize the perpetuated narrative of the Chicano people as immigrants, aliens, or illegals.

Analysis:

- In her chapter titled “The Homeland, Aztlan”, Anzaldua references Aztlan, the mythological homeland of the Aztec people, or what is referred to by some as “El Otro Mexico”. The area of Aztlan encompasses much of what today is considered the Southwestern United States and includes parts of Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, California, and Nevada. For many, Aztlan is regarded as ancestral land, something that is instrumental in the formation of a cultural identity as it allows people to tell the story of where they originated. As Anzaldua explains, during the colonial era many migrated from Mexico to the U.S. Southwest and for the indigenous people that came, “this constituted a return to place of origin, Aztlan, thus making Chicanos originally and secondarily indigenous to the southwest” (Anzaldua, 5).

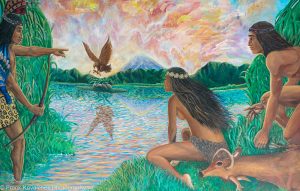

- This image is one of the many pieces of street art that can be found on the Coronado Bridge at Chicano Park in San Diego. After leaving Aztlan the Aztec people traveled through pre-colonial Mexico searching for their new homeland. According to mythology, the sight of an eagle devouring a snake would mark the area where the Aztecs were ordered to settle. On this land, they would build Tenochtitlan, now present-day Mexico City. This piece illustrates the cultural significance of a people’s historical origins and how these narratives are reflected even in a culture’s modern identity.

Analysis:

- While there is much debate on the legitimacy of Aztlan as a historical reality, what it represents is no less significant to the Chicano population. In her work, Anzaldua boldly declares, “This land was Mexico once, was Indian always and is. And will be again” (Anzaldua, 3). The concept of Aztlan leads to the creation of what is considered an imagined community. The theory of imagined communities is one that claims that communities are a product of social construction, meaning that the emphasis is placed on perceiving oneself as part of a particular group. For Chicanos/as in the United States, Aztlan becomes part of a shared history, one that becomes a unifying symbol for Mexican Americans across the country

- The photo above depicts a demonstration where Chicanos are protesting against unjust immigration policies as well as the continued violence directed at the Chicano/a population. At this demonstration, many are also attempting to publicly repeal their status as “immigrants” declaring that the land belonged to their indigenous ancestors before it was ever territory of the U.S. As the image, shows, they are emphasizing this point, rallying behind the symbol of Aztlan and carrying signs that proclaim “We didn’t cross the borders. The borders crossed us”, and “This is stolen land!”

Analysis:

- In, “Borderlands, La Frontera/ The New Mestiza” Gloria Anzaldua describes the complexities of growing up mestizaje, or mixed race, in the United States. During the colonial period, interracial and intercultural mixing took place throughout Latin America as Spanish conquistadors, indigenous peoples, and African slaves married leading to a largely mestizo/a population. According to Anzaldua, to be mestizaje means to “continually walk out of one culture and into another”, existing in a cultural space somewhere between worlds. (Anzaldua, 77). It is the shared experience of many Mexican Americans that were born in the United States, one which leaves people feeling as if they do not fully belong in either. To be Chicano/a is to be considered “other” an outsider in a white-dominated America, but for someone who has lived their entire life in the States, Mexico, and its culture also does not feel wholly familiar.

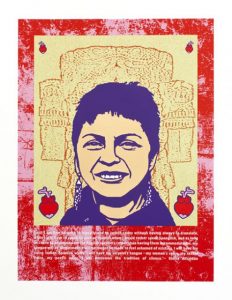

- Chicana artists Melanie Cervantes echoes these sentiments in her artwork. The illustration above is one of Cervantes’s artworks that prominently features a portrait of Gloria Anzaldua. Behind her is the image of Coatlicue, the Aztec deity that embodied the earth-mother and Cervantes notes that this inclusion references a passage from Anzaldua where she refers to the Coatlicue state, “as a type of ‘internal whirlwind’ which ‘gives and takes away life’, ‘invoking art,’ and that it is ‘alive, infused with spirit’”. The image also includes a passage from Anzaldua’s essay “How to Tame A Wild Tongue”, a passage from her book “Borderlands/ La Frontera The New Mestiza which reads, “Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate. I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my serpent’s tongue – my woman’s voice, my sexual voice, my poet’s voice. I will overcome the tradition of silence.”

Application:

Today Gloria Anzaldua’s writing is still recognized as integral Chicano/a literature that echoes the shared experiences of many Chicanos living in this country. It incorporates topics such as imagined communities and hybrid cultural identities to contend with the colonial legacy that left many indigenous North Americans both physically and culturally displaced in their own homelands. Through her work, Anzaldua was a pioneer that gave a voice to many Mexican Americans struggling to navigate the complex notion of what it means to be mestizaje, to exist in the cultural borderlands. Furthermore, as Anzaldua suggests, “To survive the Borderlands, you must live sin fronteras (without borders), be a crossroads”.

Sources:

- Anzaldua, Gloria, Norma E. Cantú, and Aída Hurtado. Borderlands =: La Frontera : The New Mestiza. 25th anniversary, fourth edition. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012. Print.

- Anzaldua, Gloria. “To Live in the Borderlands.” Power Poetry, https://powerpoetry.org/content/live-borderlands.

-

Cervantes, Melanie. “‘Tumbling down the Steps of the Temple’ A Portrait of Gloria Anzaldua.” Dignidad Rebelde, https://dignidadrebelde.com/tumbling-down-the-steps-of-the-temple-a-portrait-of-gloria-anzaldua/.

- Cruz, Alejandro De La. “Aztlan.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 26 Mar. 2006, https://www.flickr.com/photos/citoyen_du_monde_inc/117917229/in/photostream/.

-

Kovalchek, Frank. “Street Art at Chicano Park, Barrio Logan, San Diego.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 1 Jan. 2022, https://www.flickr.com/photos/72213316@N00/51792770180/in/photolist-2mUKu9d-2mUGiu6-2mUHCFG-2mUHCJh-2mUFGLB-bWgtr-2mUGiGL-2mUGiVw-2mUHCB8-2mUARJT-2mUFGZn-2mUGish-2mUAS2g-tzgWu-tzgFX-2mUHCC5-2mUFGGJ-2mUKuzy-2mUGiHY-2mUGiCc-2mUGiTn-2mUKuBH-2mUFGRb-2mUFGHL-2mUFH1j-2mUKupJ-2mUKuf5-2mUKuDw-2mUFGYF-2mUFGEQ-2mUFGUn-2mUHCzQ-2mUARYv-2mUGiM5-2mUHCvB-2mUKuCE-2mUARSd-2mUARQj-2mUFGYa-2mUFGWB-2mUFGxf-bWgtt-2mUAS3Z-2mUFGyY-2mUGiA3-2mUHCF1-bWgtu-2mUGiUV-2mUHCRr-5oobrq.

-

Project, Serie. “Tumbling down the Steps of the Temple by Melanie Cervantes (Serie Project XIX | Latino Art Studio Screen Print).” Flickr, Yahoo!, 30 July 2012, https://www.flickr.com/photos/serieproject/7678891126/in/photolist-cGyjNA-S2HgzR-5oiUvn-5oiUzZ-5oobkN-brieuq-cGDAqS-5oobvh-cGCX81-5oobwW-5oobgu-2hGDUsN-cGDAv5-brigfN-5oobgY-5oiUrZ-Sa83AQ-4Df65b-5oobwo-5oobn7-FVmWT5-rqUhtU-bEd8C8-241q4Lo-jtKvic-22FVLpK-bcZhgR-4CeWeo-pNpdf3-21HeESu-q5Mr84-21AKUoW-4Df17q-22FVj4i-q5VtWb-5uNkKb-zG2rv-hUQSsw-pNoEUC-2hGDUrW-2hGHBvs-cjc14u-hUQmJp-q5VuwE-brifG7-4Df3m9-pNpKWt-q5BfcH-gS96pX-4DaLzR.