Bridghid Davidson: The Decolonial Art of Kali Spitzer

bridghiddavidson

Preface:

Bridghid Davidson

The Decolonial Art of Kali Spitzer

CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction:

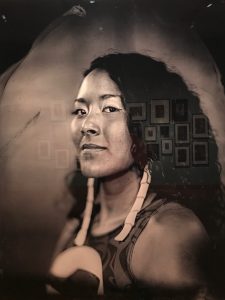

Kali Spitzer, a decolonial artist/photographer from what she refers to as the “territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations,” or Vancouver (Rutter and Youngquist, para. 17), completely embodies what it means to create decolonial art. Working mainly with photography, Spitzer creates spaces for Indigenous, queer, nonbinary, and queer people to create art with her via posing for her images. Kali Spitzer is changing the language around colonialism and helping turn the trauma into safe spaces for those most affected.

Themes:

The goal of Kali Spitzer’s work and activism is to reclaim and create safe and inclusive spaces for indigenous and LGBTQ+ people. Spitzer also works to reclaim art for indigenous people, most notably in the form of photography. Photography has often been used a tool for colonialism to justify and promote racism. Because of this, Spitzer’s work is mainly centered around reframing indigenous photography in a positive light, while also highlighting LGBTQ+ people. Through her art, Spitzer has successfully created spaces that are safe and inclusive for those that need it the most.

Analysis:

Given that Kali Spitzer’s work is centered around Indigenous photography, Spitzer works primarily in tin-type or wet-plate formats. Tin-type photography involves a somewhat complicated process using a collodion emulsion and silver halide crystals (“Tintype” Wikipedia) to develop the photo.

By going through the entire photo process from start to finish herself, Spitzer is reclaiming art for Indigenous people at every step. As an Indigenous, Jewish, and queer woman herself, Spitzer works to ensure that these groups are especially safe and represented. By “making photos” of these marginalized groups, Spitzer is rejecting colonialism and the harm that photography within colonialism has done. Spitzer takes enormous steps to ensure that everyone she “makes photos with” (she does not use the term “subjects”) (Rutter and Youngquist, para. 17) are celebrated and loved in her space. In her New York Times feature, Spitzer also states that she and the people she creates photos with are together in every step of the process, including in the darkroom (Rutter and Youngquist, para. 17).

Application:

In today’s society, safe spaces must include queer and trans people, and Spitzer’s work is an incredible example. As Spitzer is reclaiming photography from colonialism, she is also reclaiming a sense of community and tradition. By working closely with the people she is photographing, Spitzer is rejecting colonialism at literally every step. Spitzer is not simply creating indigenous art, she is reclaiming and re-inventing what it looks like to be an inclusive artist and member of society.

To see more of Kali Spitzer’s beautiful (copyrighted) art, please check out her website at https://kalispitzer.photoshelter.com/index

or her Instagram at

@Kali_Spitzer_Photography (https://www.instagram.com/kali_spitzer_photography/?hl=en)

Works Cited:

Rutter, Samuel, and Caitlin Youngquist. “10 Queer Indigenous Artists on Where Their Inspirations Have Led Them.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 Apr. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/23/t-magazine/queer-indigenous-artists.html.

“Tintype.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 26 Mar. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintype.