Chapter 6: The Politics of Public Opinion

What Does the Public Think?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why Americans hold a variety of views about politics, policy issues, and political institutions

- Identify factors that change public opinion

- Compare levels of public support for the branches of government

While attitudes and beliefs are slow to change, ideology can be influenced by events. A student might leave college with a liberal ideology but become more conservative as she ages. A first-year teacher may view unions with suspicion based on second-hand information but change his mind after reading newsletters and attending union meetings. These shifts may change the way citizens vote and the answers they give in polls. For this reason, political scientists often study when and why such changes in ideology happen, and how they influence our opinions about government and politicians.

EXPERIENCES THAT AFFECT PUBLIC OPINION

Ideological shifts are more likely to occur if a voter’s ideology is only weakly supported by their beliefs. Citizens can also hold beliefs or opinions that are contrary or conflicting, especially if their knowledge of an issue or candidate is limited. And having limited information makes it easier for them to abandon an opinion. Finally, citizens’ opinions will change as they grow older and separate from family.[1]

Citizens use two methods to form an opinion about an issue or candidate. The first is to rely on heuristics, shortcuts or rules of thumb (cues) for decision making. Political party membership is one of the most common heuristics in voting. Many voters join a political party whose platform aligns most closely with their political beliefs, and voting for a candidate from that party simply makes sense. A Republican candidate will likely espouse conservative beliefs, such as smaller government and lower taxes, that are often more appealing to a Republican voter. Studies have shown that up to half of voters make decisions using their political party identification, or party ID, especially in races where information about candidates is scarce.[2]

In non-partisan and some local elections, where candidates are not permitted to list their party identifications, voters may have to rely on a candidate’s background or job description to form a quick opinion of a candidate’s suitability. A candidate for judge may list “criminal prosecutor” as current employment, leaving the voter to determine whether a prosecutor would make a good judge.

The second method is to do research, learning background information before making a decision. Candidates, parties, and campaigns put out a large array of information to sway potential voters, and the media provide wide coverage, all of which is readily available online and elsewhere. But many voters are unwilling to spend the necessary time to research and instead vote with incomplete information.[3]

Gender, race, socio-economic status, and interest-group affiliation also serve as heuristics for decision making. Voters may assume women candidates have a stronger understanding about social issues relevant to women. Business owners may prefer to vote for a candidate with a college degree who has worked in business rather than a career politician. Other voters may look to see which candidate is endorsed by Planned Parenthood, because Planned Parenthood’s endorsement will ensure the candidate supports abortion rights.

Opinions based on heuristics rather than research are more likely to change when the cue changes. If a voter begins listening to a new source of information or moves to a new town, the influences and cues they meet will change. Even if the voter is diligently looking for information to make an informed decision, demographic cues matter. Age, gender, race, and socio-economic status will shape our opinions because they are a part of our everyday reality, and they become part of our barometer on whether a leader or government is performing well.

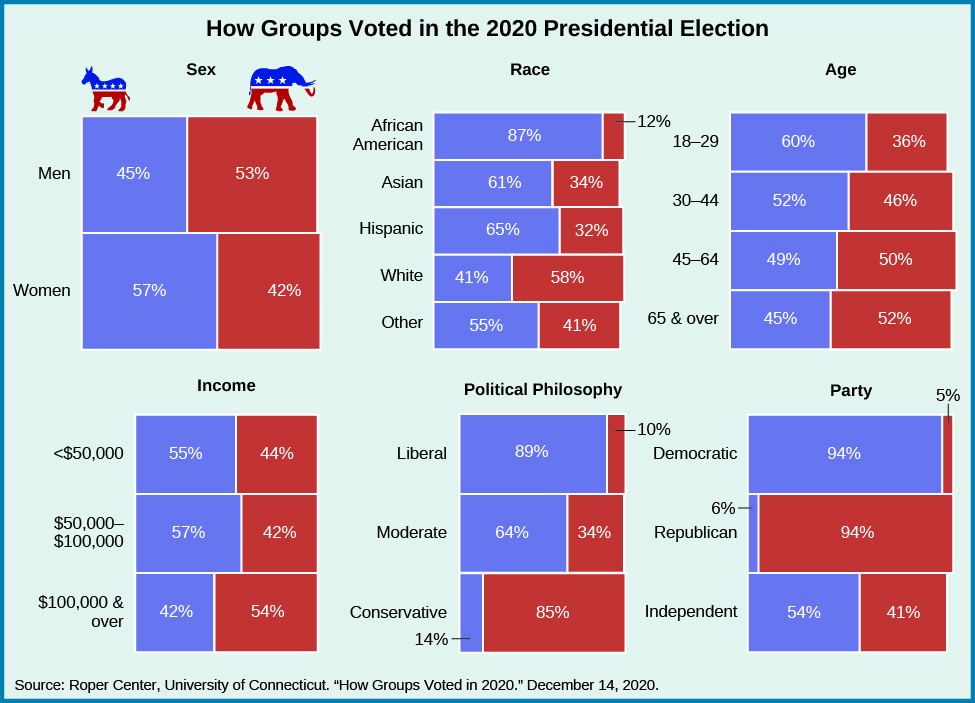

A look at the 2020 presidential election shows how the opinions of different demographic groups vary (Figure 6.12). For instance, 57 percent of women voted for Joe Biden and 53 percent of men voted for Donald Trump. Age mattered as well—60 percent of voters under thirty voted for Biden, whereas 52 percent of those over sixty-five voted for Trump. Racial groups also varied in their support of the candidates. Eighty-seven percent of African Americans and 65 percent of Hispanics voted for Biden instead of Trump. These demographic effects are likely to be strong because of shared experiences, concerns, and ideas. Citizens who are comfortable with one another will talk more and share opinions, leading to more opportunities to influence or reinforce one another.

Similar demographic effects were seen in the 2016 presidential election. For instance, 54 percent of women voted for the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, and 52 percent of men voted for the Republican candidate, Donald Trump. If considering age and race, Trump garnered percentages similar to Mitt Romney in these categories as well. And, as in 2020, households with incomes below $50,000 favored the Democratic candidate, while those households with incomes above $100,000 favored favored the Republican.[4]

The political culture of a state can also have an effect on ideology and opinion. In the 1960s, Daniel Elazar researched interviews, voting data, newspapers, and politicians’ speeches. He determined that states had unique cultures and that different state governments instilled different attitudes and beliefs in their citizens, creating political cultures. Some states value tradition, and their laws try to maintain longstanding beliefs. Other states believe government should help people and therefore create large bureaucracies that provide benefits to assist citizens. Some political cultures stress citizen involvement whereas others try to exclude participation by the masses.

State political cultures can affect the ideology and opinions of those who live in or move to them. For example, opinions about gun ownership and rights vary from state to state. Polls show that 61 percent of all Californians, regardless of ideology or political party, stated there should be more controls on who owns guns.[5] In contrast, in Texas, support for the right to carry a weapon is high. Fifty percent of self-identified Democrats—who typically prefer more controls on guns rather than fewer—said Texans should be allowed to carry a concealed weapon if they have a permit.[6] In this case, state culture may have affected citizens’ feelings about the Second Amendment and moved them away from the expected ideological beliefs.

The workplace can directly or indirectly affect opinions about policies, social issues, and political leaders by socializing employees through shared experiences. People who work in education, for example, are often surrounded by others with high levels of education. Their concerns will be specific to the education sector and different from those in other workplaces. Frequent association with colleagues can align a person’s thinking with theirs.

Workplace groups such as professional organizations or unions can also influence opinions. These organizations provide members with specific information about issues important to them and lobby on their behalf in an effort to better work environments, increase pay, or enhance shared governance. They may also pressure members to vote for particular candidates or initiatives they believe will help promote the organization’s goals. For example, teachers’ unions often support the Democratic Party because it has historically supported increased funding to public schools and universities.

Important political opinion leaders, or political elites, also shape public opinion, usually by serving as short-term cues that help voters pay closer attention to a political debate and make decisions about it. Through a talk program or opinion column, the elite commentator tells people when and how to react to a current problem or issue. Millennials and members of Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980) long used Jon Stewart of The Daily Show and later Stephen Colbert of The Colbert Report as shortcuts to becoming informed about current events. In the same way, older generations trusted Tom Brokaw and 60 Minutes. Today, most Americans, especially younger Americans, derive their news from their social media networks rather than from regularly watching a TV program.

Because an elite source can pick and choose the information and advice to provide, the door is open to covert influence if this source is not credible or honest. Voters must be able to trust the quality of the information. When elites lose credibility, they lose their audience. News agencies are aware of the relationship between citizens and elites, which is why news anchors for major networks are carefully chosen. When Brian Williams of NBC was accused of lying about his experiences in Iraq and New Orleans, he was suspended pending an investigation. Williams later admitted to several misstatements and apologized to the public, and he was removed from The Nightly News.[7]

OPINIONS ABOUT POLITICS AND POLICIES

What do Americans think about their political system, policies, and institutions? Public opinion has not been consistent over the years. It fluctuates based on the times and events, and on the people holding major office (Figure 6.13). Sometimes a majority of the public express similar ideas, but many times not. Where, then, does the public agree and disagree? Let’s look at the two-party system, and then at opinions about public policy, economic policy, and social policy.

The United States is traditionally a two-party system. Only Democrats and Republicans regularly win the presidency and, with few exceptions, seats in Congress. The majority of voters cast ballots only for Republicans and Democrats, even when third parties are represented on the ballot. Yet, citizens say they are frustrated with the current party system. Only 33 percent identify themselves as Democrats and only 29 percent as Republicans while 34 percent identify themselves as independent. Democratic membership has stayed relatively the same, but the Republican Party has lost about 5 percent of its membership over the last ten years, whereas the number of self-identified independents has grown from 30 percent in 2004 to 34 percent in 2020.[8] Given these numbers, it is not surprising that 58 percent of Americans say a third party is needed in U.S. politics today.[9]

Some of these changes in party allegiance may be due to generational and cultural shifts. Millennials and Generation Xers are more likely to support the Democratic Party than the Republican Party. In a 2015 poll, 51 percent of Millennials and 49 percent of Generation Xers stated they did, whereas only 35 percent and 38 percent, respectively, supported the Republican Party. Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) are slightly less likely than the other groups to support the Democratic Party; only 47 percent reported doing so. The Silent Generation (born in the 1920s to early 1940s) is the only cohort whose members state they support the Republican Party as a majority.[10]

Another shift in politics may be coming from the increasing number of multiracial citizens with strong cultural roots. Almost 7 percent of the population now identifies as biracial or multiracial, and that percentage is likely to grow. The number of citizens identifying as both African American and White doubled between 2000 and 2010, whereas the number of citizens identifying as both Asian American and White grew by 87 percent. The Pew study found that only 37 percent of multiracial adults favored the Republican Party, while 57 percent favored the Democratic Party.[11] And, in the 2020 presidential election, the Democratic Party placed Kamala Harris, who is of African American and Indian descent, on the Democratic ticket, producing the country’s first multiracial woman vice president. As the demographic composition of the United States changes and new generations become part of the voting population, public concerns and expectations will change as well.

At its heart, politics is about dividing scarce resources fairly and balancing liberties and rights. Public policy often becomes messy as politicians struggle to fix problems with the nation’s limited budget while catering to numerous opinions about how best to do so. While the public often remains quiet, simply answering public opinion polls or dutifully casting their votes on Election Day, occasionally citizens weigh in more audibly by protesting or lobbying.

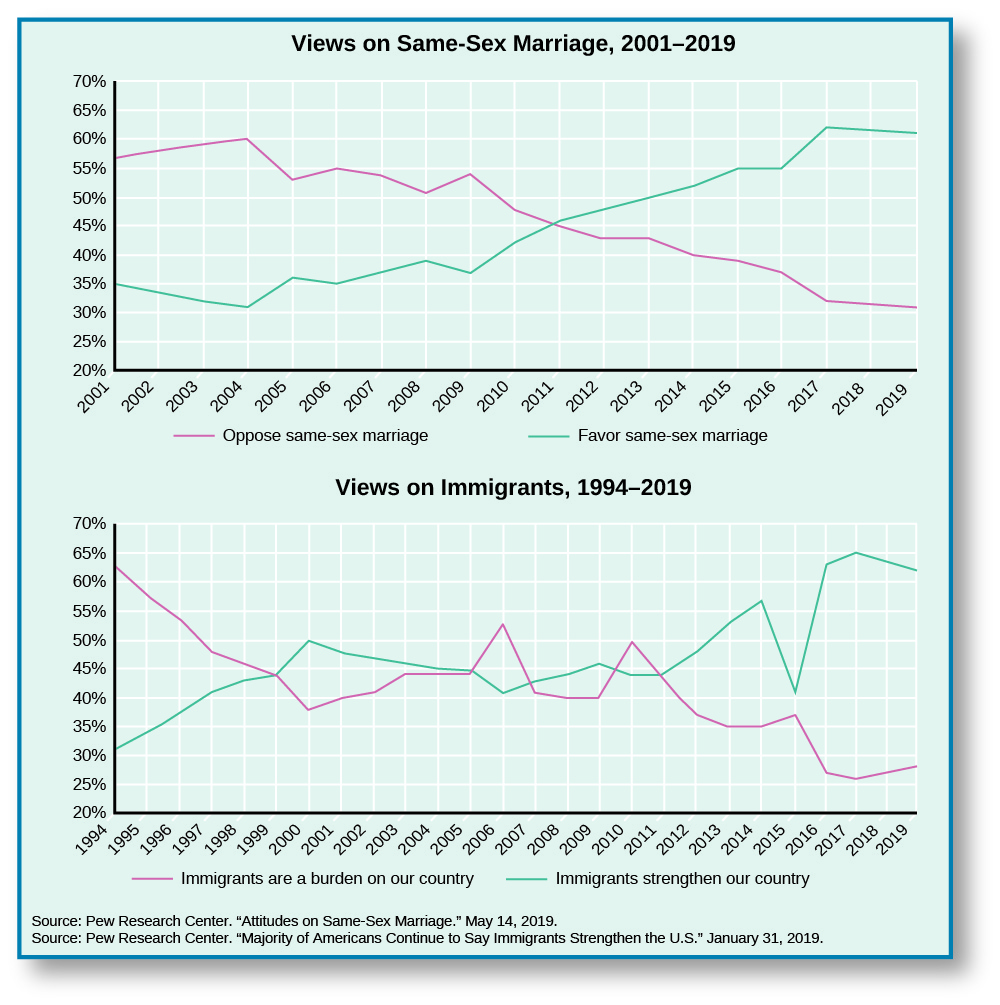

Some policy decisions are made without public input if they preserve the way money is allocated or defer to policies already in place. But policies that directly affect personal economics, such as tax policy, may cause a public backlash, and those that affect civil liberties or closely held beliefs may cause even more public upheaval. Policies that break new ground similarly stir public opinion and introduce change that some find difficult. The acceptance of same-sex marriage, for example, pitted those who sought to preserve their religious beliefs against those who sought to be treated equally under the law.

Where does the public stand on economic policy? Only 27 percent of citizens surveyed in 2021 thought the U.S. economy was in excellent or good condition,[12] yet 53 percent believed their personal financial situation was excellent to good.[13] While this seems inconsistent, it reflects the fact that we notice what is happening outside our own home. Even if a family’s personal finances are stable, members will be aware of friends and relatives who are suffering job losses or foreclosures. This information will give them a broader, more negative view of the economy beyond their own pocketbook.

Compared to strong public support for fiscal responsibility and government spending cuts a decade ago, in 2019, when asked about government spending or cuts across thirteen budget areas, there was little public support for cuts of any kind.[14] In fact, there was support for spending increases in all thirteen areas. Education and veterans benefits were the areas with the most popular support, with 72 percent of respondents supporting increased spending in these categories, and only 9 percent of respondents supporting cuts to education and 4 percent of respondents supporting cuts to veterans benefits. Even in areas where more Americans wanted to see cuts, such as assistance to the unemployed (23 percent of respondents favored decreasing spending), there was a larger group (31 percent) that favored increased spending and still another and even larger group (43 percent) wanting current spending maintained.[15] A 2020 Pew survey demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has further lessened the public’s concern with growing budget deficits.[16]

Social policy consists of government’s attempts to regulate public behavior in the service of a better society. To accomplish this, government must achieve the difficult task of balancing the rights and liberties of citizens. A person’s right to privacy, for example, might need to be limited if another person is in danger. But to what extent should the government intrude in the private lives of its citizens? In a recent survey, 54 percent of respondents believed the U.S. government was too involved in trying to deal with issues of morality.[17]

Abortion is a social policy issue that has caused controversy for nearly a century. One segment of the population wants to protect the rights of the unborn child. Another wants to protect the bodily autonomy of women and the right to privacy between a patient and her doctor. The divide is visible in public opinion polls, where 59 percent of respondents said abortion should be legal in most cases and 39 percent said it should be illegal in most cases.[18] The Affordable Care Act, which increased government involvement in health care, has drawn similar controversy. In a 2017 poll, 56 percent of respondents approved of the ACA (up 20 percent since 2013), while 38 percent expressed disapproval of the act.[19] Today, the ACA is more popular than ever. Reasons for its popularity include the fact that more Americans have health insurance, pre-existing conditions cannot be a factor in the denial of coverage, and health insurance is more affordable for many people. Much of the public’s initial frustration with the ACA came from the act’s mandate that individuals purchase health insurance or pay a fine (in order to create a large enough pool of insured people to reduce the overall cost of coverage), which some saw as an intrusion into individual decision making. The individual mandate penalty was reduced to $0 after the end of 2018.

Laws allowing same-sex marriage raise the question whether the government should be defining marriage and regulating private relationships in defense of personal and spousal rights. Public opinion has shifted dramatically over the last twenty years. In 1996, only 27 percent of Americans felt same-sex marriage should be legal, but recent polls show support has increased to 70 percent.[20] Despite this sharp increase, a number of states had banned same-sex marriage until the Supreme Court decided, in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), that states were obliged to give marriage licenses to couples of the same sex and to recognize out-of-state, same-sex marriages.[21] Some churches and businesses continue to argue that no one should be compelled by the government to recognize or support a marriage between members of the same sex if it conflicts with their religious beliefs.[22] Undoubtedly, the issue will continue to cause a divide in public opinion.

Another area where social policy must balance rights and liberties is public safety. Regulation of gun ownership incites strong emotions, because it invokes the Second Amendment and state culture. Of those polled nationwide, when asked whether the government should prioritize reducing gun violence or protecting the right to bear arms, 50 percent of Americans favored reducing gun violence, while 43 percent favored emphasizing gun rights.[23] Fifty-three percent feel there should be stronger controls over gun ownership.[24] These numbers change from state to state, however, because of political culture. Immigration similarly causes strife, with citizens fearing increases in crime and social spending due to large numbers of people entering the United States illegally. Yet, 69 percent of respondents did believe there should be a path to citizenship for non-documented residents already in the country.[25] And while the national government’s drug policy still lists marijuana as an illegal substance, 68 percent of respondents stated they would agree if the government legalized marijuana.[26]

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a rich set of data on public opinion and significant dynamics in opinion over time. Early on, Americans across the spectrum expressed similar concerns about the outbreak and the path forward. However, within a few months, a partisan divide emerged on how widespread the disease was and what measures should be in place to control it. Democratic respondents saw the disease as more widespread and in need of strong government controls, while Republicans raised concerns about scientific data, the propensity of testing, and too much control by the government.[27]

PUBLIC OPINION AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

Public opinion about American institutions is measured in public approval ratings rather than in questions of choice between positions or candidates. The congressional and executive branches of government are the subject of much scrutiny and discussed daily in the media. Polling companies take daily approval polls of these two branches. The Supreme Court makes the news less frequently, and approval polls are more likely after the court has released major opinions. All three branches, however, are susceptible to swings in public approval in response to their actions and to national events. Approval ratings are generally not stable for any of the three. We next look at each in turn.

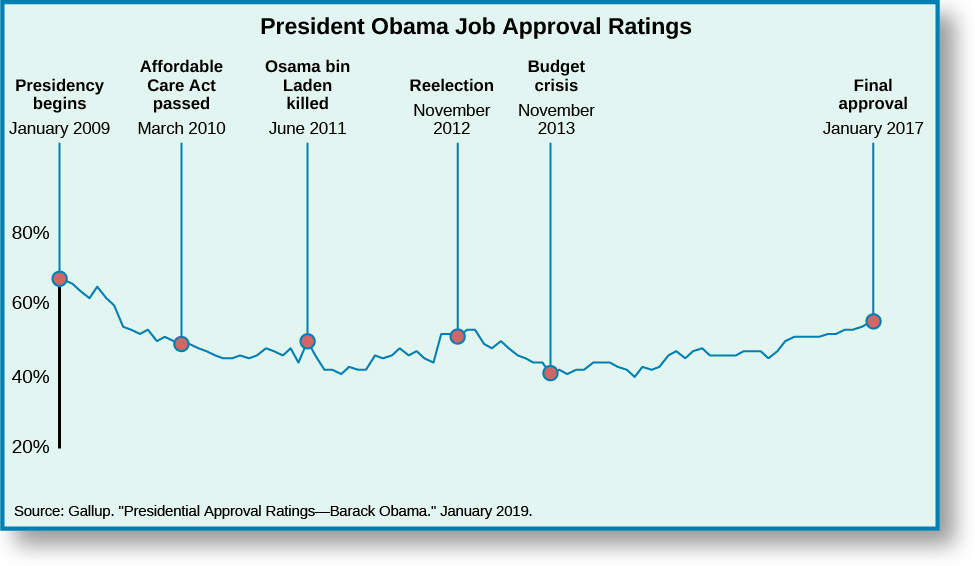

The president is the most visible member of the U.S. government and a lightning rod for disagreement. Presidents are often blamed for the decisions of their administrations and political parties, and are held accountable for economic and foreign policy downturns. For these reasons, they can expect their approval ratings to slowly decline over time, increasing or decreasing slightly with specific events. On average, presidents enjoy a 66 percent approval rating when starting office, but it drops to 53 percent by the end of the first term. Presidents serving a second term average a beginning approval rating of 55.5 percent, which falls to 47 percent by the end of office. For most of his term, President Obama’s presidency followed the same trend. He entered office with a public approval rating of 67 percent, which fell to 54 percent by the third quarter, dropped to 52 percent after his reelection, and, as of October 2015, was at 46 percent. However, after January 2016, his approval rating began to climb, and he left office with an approval rating of 59 percent (Figure 6.14). President Trump experienced significantly lower approval ratings than average, taking the oath of office with an approval rating of 45 percent and leaving office in January 2021 at 34 percent. Moreover, throughout his presidency, Trump’s approval rate never rose above 49 percent. President Biden’s approval was at 54 percent as of March 2021.[28]

Events during a president’s term may spike public approval ratings. George W. Bush’s public approval rating jumped from 51 percent on September 10, 2001, to 86 percent by September 15 following the 9/11 attacks. His father, George H. W. Bush, had received a similar spike in approval ratings (from 58 to 89 percent) following the end of the first Persian Gulf War in 1991.[29] These spikes rarely last more than a few weeks, so presidents try to quickly use the political capital they bring. For example, the 9/11 rally effect helped speed a congressional joint resolution authorizing the president to use troops, and the “global war on terror” became a reality.[30] The rally was short-lived, and support for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan quickly deteriorated post-2003.[31]

Some presidents have had higher or lower public approval than others, though ratings are difficult to compare, because national and world events that affect presidential ratings are outside a president’s control. Several chief executives presided over failing economies or wars, whereas others had the benefit of strong economies and peace. Gallup, however, gives an average approval rating for each president across the entire period served in office. George W. Bush’s average approval rating from 2001 to 2008 was 49.4 percent. Ronald Reagan’s from 1981 to 1988 was 52.8 percent, despite his winning all but thirteen electoral votes in his reelection bid. Bill Clinton’s average approval from 1993 to 2000 was 55.1 percent, including the months surrounding the Monica Lewinsky scandal and his subsequent impeachment. To compare other notable presidents, John F. Kennedy averaged 70.1 percent and Richard Nixon 49 percent.[32] Kennedy’s average was unusually high because his time in office was short; he was assassinated before he could run for reelection, leaving less time for his ratings to decline. Nixon’s unusually low approval ratings reflect several months of media and congressional investigations into his involvement in the Watergate affair, as well as his resignation in the face of likely impeachment.

LINK TO LEARNING

Gallup polling has tracked approval ratings for all presidents since Harry Truman. The Presidential Job Approval Center allows you to compare weekly approval ratings for all tracked presidents, as well as their average approval ratings.

MILESTONE

Public Mood and Watershed Moments

Polling is one area of U.S. politics in which political practitioners and political science scholars interact. Each election cycle, political scientists help media outlets interpret polling, statistical data, and election forecasts. One particular watershed moment in this regard occurred when Professor James Stimson, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, developed his aggregated measure of public mood. This measure takes a variety of issue positions and combines them to form a general ideology about the government. According to Professor Stimson, the American electorate became more conservative in the 1970s and again in the 1990s, as demonstrated by Republican gains in Congress. With this public mood measure in mind, political scientists can explain why and when Americans allowed major policy shifts. For example, the Great Society’s expansion of welfare and social benefits occurred during the height of liberalism in the mid-1960s, while the welfare cuts and reforms of the 1990s occurred during the nation’s move toward conservatism. Tracking conservative and liberal shifts in the public’s ideology allows policy analysts to predict whether voters are likely to accept or reject major policies.

What other means of measuring the public mood do you think might be effective and reliable? How would you implement them? Do you agree that watershed moments in history signal public mood changes? If so, give some examples. If not, why not?

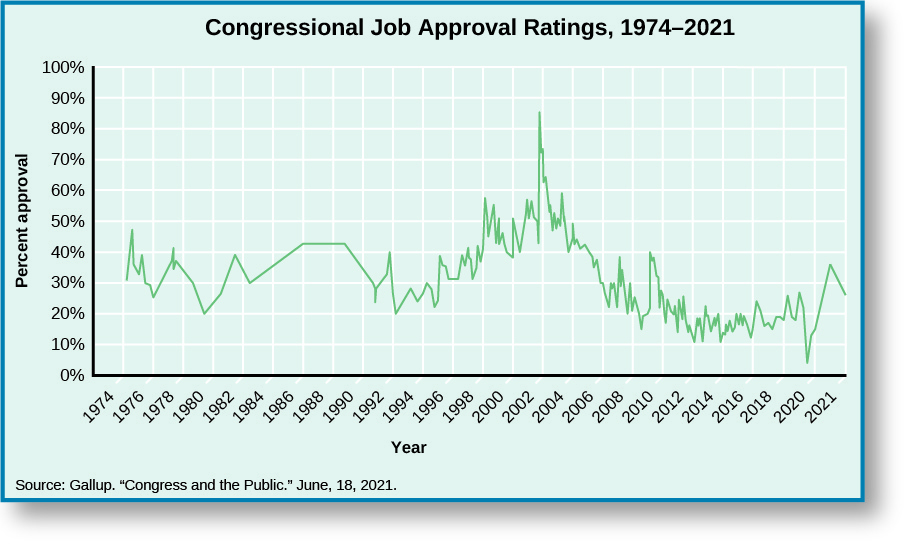

Congress as an institution has historically received lower approval ratings than presidents, a striking result because individual senators and representatives are generally viewed favorably by their constituents. While congressional representatives almost always win reelection and are liked by their constituents back home, the institution itself is often vilified as representing everything that is wrong with politics and partisanship.

As of March 2021 public approval of Congress sat at around 34 percent.[33] For most of the last forty years, congressional approval levels have bounced between 20 percent and 60 percent, but in the last fifteen years they have regularly fallen below 40 percent. Like President George W. Bush, Congress experienced a short-term jump in approval ratings immediately following 9/11, likely because of the rallying effect of the terrorist attacks. Congressional approval had dropped back below 50 percent by early 2003 (Figure 6.15).

While presidents are affected by foreign and domestic events, congressional approval is mainly affected by domestic events. When the economy rebounds or gas prices drop, public approval of Congress tends to go up. But when party politics within Congress becomes a domestic event, public approval falls. The passage of revenue bills has become an example of such an event, because deficits require Congress to make policy decisions before changing the budget. Deficit and debt are not new to the United States. Congress and presidents have attempted various methods of controlling debt, sometimes successfully and sometimes not. In the past three decades alone, however, several prominent examples have shown how party politics make it difficult for Congress to agree on a budget without a fight, and how these fights affect public approval.

In 1995, Democratic president Bill Clinton and the Republican Congress hit a notable stalemate on the national budget. In this case, the Republicans had recently gained control of the House of Representatives and disagreed with Democrats and the president on how to cut spending and reduce the deficit. The government shut down twice, sending non-essential employees home for a few days in November, and then again in December and January.[34] Congressional approval fell during the event, from 35 to 30 percent.[35]

Divisions between the political parties, inside the Republican Party, and between Congress and the president became more pronounced over the next fifteen years, with the media closely covering the political strife.[36] In 2011, the United States reached its debt ceiling, or maximum allowed debt amount. After much debate, the Budget Control Act was passed by Congress and signed by President Obama. The act increased the debt ceiling, but it also reduced spending and created automatic cuts, called sequestrations, if further legislation did not deal with the debt by 2013. When the country reached its new debt ceiling of $16.4 trillion in 2013, short-term solutions led to Congress negotiating both the debt ceiling and the national budget at the same time. The timing raised the stakes of the budget, and Democrats and Republicans fought bitterly over the debt ceiling, budget cuts, and taxes. Inaction triggered the automatic cuts to the budget in areas like defense, the courts, and public aid. By October, approximately 800,000 federal employees had been sent home, and the government went into partial shut-down for sixteen days before Congress passed a bill to raise the debt ceiling.[37] The handling of these events angered Americans, who felt the political parties needed to work together to solve problems rather than play political games. During the 2011 ceiling debate, congressional approval fell from 18 to 13 percent, while in 2013, congressional approval fell to a new low of 9 percent in November.[38]

The Supreme Court generally enjoys less visibility than the other two branches of government, which leads to more stable but also less frequent polling results. Indeed, 22 percent of citizens surveyed in 2014 had never heard of Chief Justice John Roberts, the head of the Supreme Court.[39] The court is protected by the justices’ non-elected, non-political positions, which gives them the appearance of integrity and helps the Supreme Court earn higher public approval ratings than presidents and Congress. To compare, between 2000 and 2010, the court’s approval rating bounced between 50 and 60 percent. During this same period, Congress had a 20 to 40 percent approval rating.

The Supreme Court’s approval rating is also less susceptible to the influence of events. Support of and opinions about the court are affected when the justices rule on highly visible cases that are of public interest or other events occur that cause citizens to become aware of the court.[40] For example, following the Bush v. Gore case (2000), in which the court instructed Florida to stop recounting ballots and George W. Bush won the Electoral College, 80 percent of Republicans approved of the court, versus only 42 percent of Democrats.[41] Twelve years later, when the Supreme Court’s ruling in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) let stand the Affordable Care Act’s requirement of individual coverage, approval by Democrats increased to 68 percent, while Republican support dropped to 29 percent.[42] In 2015, following the handing down of decisions in King v. Burwell (2015) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which allowed the Affordable Care Act’s subsidies and prohibited states from denying same-sex marriage, respectively, 45 percent of people said they approved of the way the Supreme Court handled its job, down 4 percent from before the decisions.[43]

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 6.3 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Michael S. Lewis-Beck, William G. Jacoby, Helmut Norpoth, and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2008. American Vote Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ↵

- Samuel Popkin. 2008. The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. Michael S. Lewis-Beck, William G. Jacoby, Helmut Norpoth, and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2008. American Vote Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ↵

- Scott Ashworth, and Ethan Bueno De Mesquita. 2014. “Is Voter Competence Good for Voters? Information, Rationality, and Democratic Performance.” American Political Science Review 108 (3): 565–587. ↵

- "How Groups Voted in 2020," Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at Cornell University, https://beta.roper.center/how-groups-voted-2020 (June 2021). ↵

- Josh Richman, “Field Poll: California Voters Favor Gun Controls Over Protecting Second Amendment Rights,” San Jose Mercury News, 26 February 2013. ↵

- UT Austin. 2015. “Agreement with Concealed Carry Laws.” UT Austin Texas Politics Project. February 2015. http://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/set/agreement-concealed-carry-laws-february-2015#party-id (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Stephen Battaglio, “Brian Williams Will Leave ‘NBC Nightly News’ and Join MSNBC,” LA Times, 18 June 2015. ↵

- Pew Research Center, "What the 2020 Electorate Looks Like by Party, Race and Ethnicity, Age, Education and Religion," Pew Research Center, October 26, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/26/what-the-2020-electorate-looks-like-by-party-race-and-ethnicity-age-education-and-religion/. ↵

- Jeffrey Jones. 2014. “Americans Continue to Say a Third Political Party is Needed.” Gallup. September 24, 2014. http://www.gallup.com/poll/177284/americans-continue-say-third-political-party-needed.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “A Different Look at Generations and Partisanship.” Pew Research Center. April 30, 2015. http://www.people-press.org/2015/04/30/a-different-look-at-generations-and-partisanship/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “Multiracial in America.” Pew Research Center. June 11, 2015. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- "Economy," Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1609/consumer-views-economy.aspx (June 2021). ↵

- Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Anna Brown, and Rachel Minkin, "A Year Into the Pandemic, Long-Term Financial Impact Weighs Heavily on Many Americans," Pew Research Center, 5 March 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/03/05/a-year-into-the-pandemic-long-term-financial-impact-weighs-heavily-on-many-americans/. ↵

- Frank Newport. 2011. “Americans Blame Wasteful Government Spending for Deficit.” Gallup. April 29, 2011. http://www.gallup.com/poll/147338/Americans-Blame-Wasteful-Government-Spending-Deficit.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- "Little Public Support for Reductions in Federal Spending," Pew Research Center, 11 April 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/04/11/little-public-support-for-reductions-in-federal-spending/#widening-partisan-gap-in-views-of-spending-on-foreign-aid. ↵

- Drew Desilver, "The U.S. Budget Deficit is Rising Amind COVID-19, but Public Concern about It Is Falling," Pew Research Center, 13 August 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/13/the-u-s-budget-deficit-is-rising-amid-covid-19-but-public-concern-about-it-is-falling/. ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2011. “Domestic Issues and Social Policy.” Pew Research Center. May 4, 2011. http://www.people-press.org/2011/05/04/section-8-domestic-issues-and-social-policy/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- "Public Opinion on Abortion," Pew Research Center, 29 August 2019, https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion/. ↵

- Hannah Fingerhut, "For the First Time, More Americans Say 2010 Health Care Law Has Had a Positive Than Negative Impact on U.S.," Pew Research Center, 11 December 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/11/for-the-first-time-more-americans-say-2010-health-care-law-has-had-a-positive-than-negative-impact-on-u-s/. ↵

- Justin McCarthy, "Record-High 70% in U.S. Support Same-Sex Marriage," Gallup, 8 June 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/350486/record-high-support-same-sex-marriage.aspx. ↵

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015). ↵

- National Conference of State Legislatures. 2015. “Same Sex Marriage Laws.” National Conference of State Legislatures. June 26, 2015. http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/same-sex-marriage-laws.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Emily Guskin and Scott Clement, "Support for New Gun Laws Falls from Peak after Parkland Shooting, Post-ABC Poll Finds," 28 April 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/04/28/support-new-gun-laws-falls-peak-after-parkland-shooting-post-abc-poll-finds/. ↵

- Pew Research Center, "Gun Policy," Pew Research Center, 20 April 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/topic/politics-policy/political-issues/gun-policy/. ↵

- Joseph Guzman, "Majority of Americans Back Path to Citizenship for Undocumented Immigrants, New Poll Finds," The Hill, 4 February 2021, https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/537370-majority-of-americans-back-path-to-citizenship-for-undocumented. ↵

- Dhrumil Mehta, "Americans from Both Parties Want Weed To Be Legal. Why Doesn't the Federal Government Agree?" FiveThirtyEight, 23 April 2021, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/marijuana-legalization-is-super-popular-why-hasnt-it-happened-nationally/. ↵

- https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/a-year-of-u-s-public-opinion-on-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ ↵

- Gallup interactive Presidential Job Approval Center. https://news.gallup.com/interactives/185273/r.aspx?g_source=WWWV7HP&g_medium=topic&g_campaign=tiles. ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Presidential Approval Ratings – George W. Bush.” Gallup. June 20, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/116500/Presidential-Approval-Ratings-George-Bush.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- 115 STAT. 2001. “224. Public Law 107-40. Joint Resolution.” 107th Congress. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ40/pdf/PLAW-107publ40.pdf (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2008. “Public Attitudes Towards the War in Iraq: 2003-2008.” Pew Research Center. March 19, 2008. http://www.pewresearch.org/2008/03/19/public-attitudes-toward-the-war-in-iraq-20032008/ (February 18, 2016); Pew Research Center. 2014. “More Now See Failure than Success in Iraq, Afghanistan.” Pew Research Center. January 30, 2014. http://www.people-press.org/2014/01/30/more-now-see-failure-than-success-in-iraq-afghanistan/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Presidential Job Approval Center.” Gallup. June 20, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/124922/Presidential-Job-Approval-Center.aspx?utm_source=PRESIDENTIAL_JOB_APPROVAL&utm_medium=topic&utm_campaign=tiles (February 18, 2016). ↵

- “Congress and the Public,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/Congress-Public.aspx (June 1, 2021). ↵

- Neil Irwin, “The 1995 Shutdown, from a Budget Official’s Perspective,” Washington Post, 27 September 2013. ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Congress and the Public.” Gallup. June 21, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/Congress-Public.aspx (February 18, 2016); Jeffrey Jones. 2007. “Congress Approval Rating Matches Historical Low.” Gallup. August 21, 2007. http://www.gallup.com/poll/28456/congress-approval-rating-matches-historical-low.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Dan Merica. 2013. “1995 and 2013: Three Differences Between the Two Shutdowns.” CNN. October 4, 2013. http://www.cnn.com/2013/10/01/politics/different-government-shutdowns/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Paul Lewis, “US Shutdown Drags Into Second Day as Republicans Eye Fresh Debt Ceiling Crisis,” Guardian, 2 October 2013. ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Congress and the Public.” Gallup. June 21, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/Congress-Public.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Andrew Dugan. 2014. “Americans’ Approval of Supreme Court New All-Time Low.” Gallup. July 19, 2014. http://www.gallup.com/poll/163586/americans-approval-supreme-court-near-time-low.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- James L. Gibson, and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009. “Knowing the Supreme Court? A Reconsideration of Public Ignorance of the High Court.” Journal of Politics 71 (2): 429–441. ↵

- Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000). ↵

- National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012); Andrew Dugan. 2014. “Americans’ Approval of Supreme Court New All-Time Low.” Gallup. July 19, 2014. http://www.gallup.com/poll/163586/americans-approval-supreme-court-near-time-low.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. 473 (2015); Gallup Polling. 2015. “Supreme Court.” Gallup Polling. http://www.gallup.com/poll/4732/supreme-court.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

shortcuts or generalizations for decision making

the prevailing political attitudes and beliefs within a society or region

a political opinion leader who alerts the public to changes or problems