Chapter 5: Civil Rights

What Are Civil Rights and How Do We Identify Them?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the concept of civil rights

- Describe the standards that courts use when deciding whether a discriminatory law or regulation is unconstitutional

- Identify three core questions for recognizing a civil rights problem

The belief that people should be treated equally under the law is one of the cornerstones of political thought in the United States. Yet not all citizens have been treated equally throughout the nation’s history, and some are treated differently even today. For example, until 1920, nearly all women in the United States lacked the right to vote. Black men received the right to vote in 1870, but as late as 1940, only 3 percent of African American adults living in the South were registered to vote, due largely to laws designed to keep them from the polls.[1] Americans were not allowed to enter into legal marriage with a member of the same sex in many U.S. states until 2015. Some types of unequal treatment are considered acceptable in some contexts, while others are clearly not. No one would consider it acceptable to allow a ten-year-old to vote, because a child lacks the ability to understand important political issues, but all reasonable people would agree that it is wrong to mandate racial segregation or to deny someone voting rights on the basis of race. It is important to understand which types of inequality are unacceptable and why.

DEFINING CIVIL RIGHTS

Essentially, civil rights are guarantees by the government that it will treat people equally—particularly people belonging to groups that have historically been denied the same rights and opportunities as others. The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution enacted the Declaration of Independence’s proclamation that “all men are created equal” by providing de jure equal treatment under the law. According to Chief Justice Earl Warren in the Supreme Court case of Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), “discrimination may be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process.”[2] Additional guarantees of equality were provided in 1868 by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states, in part, that “No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Thus, between the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, neither state governments nor the federal government may treat people unequally unless unequal treatment is necessary to maintain important governmental interests such as public safety.

We can contrast civil rights with civil liberties, which are limitations on government power designed to protect our fundamental freedoms. For example, the Eighth Amendment prohibits the application of “cruel and unusual punishments” to those convicted of crimes, a limitation on the power of members of each governmental branch: judges, law enforcement, and lawmakers. As another example, the guarantee of equal protection means the laws and the Constitution must be applied on an equal basis, limiting the government’s ability to discriminate or treat some people differently, unless the unequal treatment is based on a valid reason, such as age. A law that imprisons men twice as long as women for the same offense, or restricting people with disabilities from contacting members of Congress, would treat some people differently from others for no valid reason and would therefore be unconstitutional. According to the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, “all persons similarly circumstanced shall be treated alike.”[3] If people are not similarly circumstanced, however, they may be treated differently. Asian Americans and Latinos overstaying a visa are similarly circumstanced; however, a blind driver or a ten-year-old driver is differently circumstanced than a sighted, adult driver.

IDENTIFYING DISCRIMINATION

Laws that treat one group of people differently from others are not always unconstitutional. In fact, the government engages in legal discrimination quite often. In most states, you must be eighteen years old to smoke cigarettes and twenty-one to drink alcohol; these laws discriminate against the young. To get a driver’s license so you can legally drive a car on public roads, you have to be a minimum age and pass tests showing your knowledge, practical skills, and vision. Some public colleges and universities run by the government have an open admission policy, which means the school admits all who apply, but others require that students have a high school diploma or a particular score on the SAT or ACT or a GPA above a certain number. This is a kind of discrimination, because these requirements treat people who do not have a high school diploma or a high enough GPA or SAT score differently. How can the federal, state, and local governments discriminate in all these ways even though the equal protection clause seems to suggest that everyone be treated the same?

The answer to this question lies in the purpose of the discriminatory practice. In most cases when the courts are deciding whether discrimination is unlawful, the government has to demonstrate only that it has a good reason to do so. Unless the person or group challenging the law can prove otherwise, the courts will generally decide the discriminatory practice is allowed. In these cases, the courts are applying the rational basis test. That is, as long as there’s a reason for treating some people differently that is “rationally related to a legitimate government interest,” the discriminatory act or law or policy is acceptable.[4] For example, since letting blind people operate cars would be dangerous to others on the road, the law forbidding them to drive is reasonably justified on the grounds of safety and is therefore allowed even though it discriminates against the blind. Similarly, when universities and colleges refuse to admit students who fail to meet a certain test score or GPA, they can discriminate against students with weaker grades and test scores because these students most likely do not yet possess the knowledge or skills needed to do well in their classes and graduate from the institution. The universities and colleges have a legitimate reason for denying these students entrance.

The courts, however, are much more skeptical when it comes to certain other forms of discrimination. Because of the United States’ history of ethnic, racial, gender, and religious discrimination, the courts apply more stringent rules to policies, laws, and actions that discriminate on these bases (race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or national origin).[5]

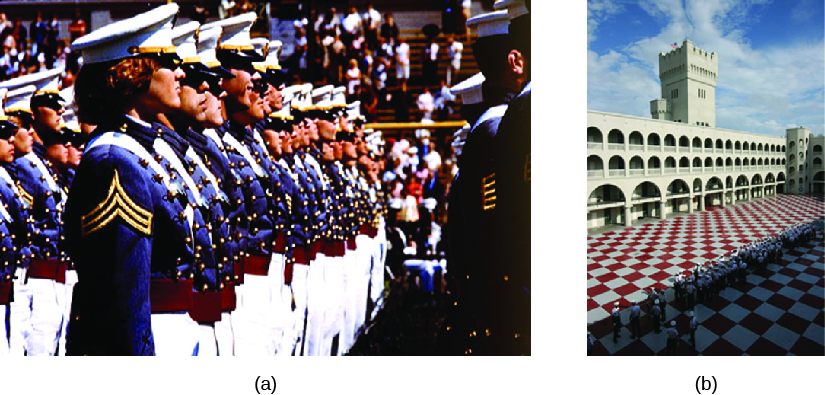

Discrimination based on gender or sex is generally examined with intermediate scrutiny. The standard of intermediate scrutiny was first applied by the Supreme Court in Craig v. Boren (1976) and again in Clark v. Jeter (1988).[6] It requires the government to demonstrate that treating men and women differently is “substantially related to an important governmental objective.” This puts the burden of proof on the government to demonstrate why the unequal treatment is justifiable, not on the individual who alleges unfair discrimination has taken place. In practice, this means laws that treat men and women differently are sometimes upheld, although usually they are not. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, the courts ruled that states could not operate single-sex institutions of higher education and that such schools, like South Carolina’s military college The Citadel, shown in Figure 5.2, must admit both male and female students.[7] Women in the military are now also allowed to serve in all combat roles, although the courts have continued to allow the Selective Service System (the draft) to register only men and not women.[8]

Discrimination against members of racial, ethnic, or religious groups or those of various national origins is reviewed to the greatest degree by the courts, which apply the strict scrutiny standard in these cases. Under strict scrutiny, the burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate that there is a compelling governmental interest in treating people from one group differently from those who are not part of that group—the law or action can be “narrowly tailored” to achieve the goal in question, and that it is the “least restrictive means” available to achieve that goal.[9] In other words, if there is a non-discriminatory way to accomplish the goal in question, discrimination should not take place. In the modern era, laws and actions that are challenged under strict scrutiny have rarely been upheld. Strict scrutiny, however, was the legal basis for the Supreme Court’s 1944 upholding of the legality of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, discussed later in this chapter.[10] Finally, affirmative action consists of government programs and policies designed to benefit members of groups historically subject to discrimination. Much of the controversy surrounding affirmative action is about whether strict scrutiny should be applied to these cases.

*Watch this video to learn more about affirmative action.

PUTTING CIVIL RIGHTS IN THE CONSTITUTION

At the time of the nation’s founding, of course, the treatment of many groups was unequal: the rights of women were decidedly fewer than those of men, and neither they, the hundreds of thousands of enslaved people of African descent, or indigenous Americans were considered fully human, let alone U.S. citizens. While the early United States was perhaps a more inclusive society than most of the world at that time, equal treatment of all remained a radical idea.

The aftermath of the Civil War marked a turning point for civil rights. The Republican majority in Congress was enraged by the actions of the reconstituted governments of the southern states. In these states, many former Confederate politicians and their sympathizers returned to power and attempted to circumvent the Thirteenth Amendment’s freeing of enslaved men and women by passing laws known as the Black codes. These laws were designed to reduce formerly enslaved people to the status of serfs or indentured servants. Black people were not just denied the right to vote, but also could be arrested and jailed for vagrancy or idleness if they lacked jobs. Black people were excluded from public schools and state colleges and were subject to violence at the hands of White people (Figure 5.3).[11]

![An image of a sketch of a building on fire. Several people are standing outside the building. Some of the people are armed. At the bottom of the image reads “Scenes in Memphis, Tennessee, during the riot—burning a freedmen’s school-house. [Sketched by A. R. W.]”.](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/sites/1893/2023/08/fig-5-3.jpeg)

To override the southern states’ actions, lawmakers in Congress proposed two amendments to the Constitution designed to give political equality and power to formerly enslaved people. Once passed by Congress and ratified by the necessary number of states, these became the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In addition to including the equal protection clause as noted above, the Fourteenth Amendment also was designed to ensure that the states would respect the civil liberties of freed people. The Fifteenth Amendment was proposed to secure the right to vote for Black men, which will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

IDENTIFYING CIVIL RIGHTS ISSUES

Looking back, it’s relatively easy to identify civil rights issues that arose, looking into the future is much harder. For example, few people fifty years ago would have identified the rights of gay or transgender Americans as an important civil rights issue, or predicted it would become one. Similarly, in past decades the rights of those with disabilities, particularly intellectual disabilities, were often ignored by the public at large. Many people with disabilities were institutionalized and given little further thought, and until very recently, laws remained on the books in some states allowing those with intellectual or developmental disabilities to be subject to forced sterilization.[12] Today, most of us view this treatment as barbaric.

Clearly, then, new civil rights issues can emerge over time. How can we, as citizens, identify them as they emerge and distinguish genuine claims of discrimination from claims by those who have merely been unable to convince a majority to agree with their viewpoints? For example, how do we decide if sixteen-year-olds are discriminated against because they are not allowed to vote, as some U.S. lawmakers are starting to suggest? We can identify true discrimination by applying the following analytical process:

- Which groups? First, identify the group of people who are facing discrimination.

- Which right(s) are threatened? Second, what right or rights are being denied to members of this group?

- What do we do? Third, what can the government do to bring about a fair situation for the affected group? Is proposing and enacting such a remedy realistic?

GET CONNECTED!

Join the Fight for Civil Rights

One way to get involved in the fight for civil rights is to stay informed. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) is a not-for-profit advocacy group based in Montgomery, Alabama. Lawyers for the SPLC specialize in civil rights litigation and represent many people whose rights have been violated, from victims of hate crimes to undocumented immigrants. They provide summaries of important civil rights cases under their Docket section.

Activity: Visit the SPLC website to find current information about a variety of different hate groups. In what part of the country do hate groups seem to be concentrated? Where are hate incidents most likely to occur? What might be some reasons for this?

LINK TO LEARNING

Civil rights institutes are found throughout the United States and especially in the south. One of the most prominent civil rights institutes is the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which is located in Alabama

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 5.1 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Constitutional Rights Foundation. “Race and Voting in the Segregated South,” http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/race-and-voting-in-the-segregated-south (April 10, 2016). ↵

- Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). ↵

- Phyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982); F. S. Royster Guano v. Virginia, 253 U.S. 412 (1920). ↵

- Cornell University Law School: Legal Information Institute. “Rational Basis,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/rational_basis (April 10, 2016); Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502 (1934). ↵

- United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938). ↵

- Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976); Clark v. Jeter, 486 U.S. 456 (1988). ↵

- Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718 (1982); United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996). ↵

- Matthew Rosenberg and Dave Philipps, “All Combat Roles Open to Women, Defense Secretary Says,” New York Times, 3 December 2015; Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57 (1981). ↵

- Johnson v. California, 543 U.S. 499 (2005). ↵

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). ↵

- “Mississippi Black Code,” https://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/122/recon/code.html (April 10, 2016); “Black Codes and Pig Laws,” http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/black-codes/ (April 10, 2016). ↵

- Catherine K. Harbour, and Pallab K. Maulik. 2010. “History of Intellectual Disability.” In International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation, eds. J. H. Stone and M. Blouin. http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/143/ (April 10, 2016). ↵

a provision of the Fourteenth Amendment that requires the states to treat all residents equally under the law

the standard used by the courts to decide most forms of discrimination; the burden of proof is on those challenging the law or action to demonstrate there is no good reason for treating them differently from other citizens

the standard used by the courts to decide cases of discrimination based on gender and sex; burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate an important governmental interest is at stake in treating men differently from women

the standard used by the courts to decide cases of discrimination based on race, ethnicity, national origin, or religion; burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate a compelling governmental interest is at stake and no alternative means are available to accomplish its goals

the use of programs and policies designed to assist groups that have historically been subject to discrimination

laws passed immediately after the Civil War that discriminated against freed people and other African Americans and deprived them of their rights