Chapter 7: Voting and Elections

Voter Registration

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify ways the U.S. government has promoted voter rights and registration

- Summarize similarities and differences in states’ voter registration methods

- Analyze ways states increase voter registration and decrease fraud

Before most voters are allowed to cast a ballot, they must register to vote in their state. This process may be as simple as checking a box on a driver’s license application or as difficult as filling out a long form with complicated questions. Registration allows governments to determine which citizens are allowed to vote and, in some cases, from which list of candidates they may select a party nominee. Ironically, while government wants to increase voter turnout, the registration process may prevent various groups of citizens and non-citizens from participating in the electoral process.

VOTER REGISTRATION ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

Elections are state-by-state contests. They include general elections for president and statewide offices (e.g., governor and U.S. senator), and they are often organized and paid for by the states. Because political cultures vary from state to state, the process of voter registration similarly varies. For example, suppose an 85-year-old retiree with an expired driver’s license wants to register to vote. He or she might be able to register quickly in California or Florida, but a current government ID might be required prior to registration in Texas or Indiana.

The varied registration and voting laws across the United States have long caused controversy. In the aftermath of the Civil War, southern states enacted literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other requirements intended to disenfranchise Black voters in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Literacy tests were long and detailed exams on local and national politics, history, and more. They were often administered arbitrarily with more African Americans required to take them than White people[1] Poll taxes required voters to pay a fee to vote. Grandfather clauses exempted individuals from taking literacy tests or paying poll taxes if they or their fathers or grandfathers had been permitted to vote prior to a certain point in time. While the Supreme Court determined that grandfather clauses were unconstitutional in 1915, states continued to use poll taxes and literacy tests to deter potential voters from registering.[2] States also ignored instances of violence and intimidation against African Americans wanting to register or vote.[3]

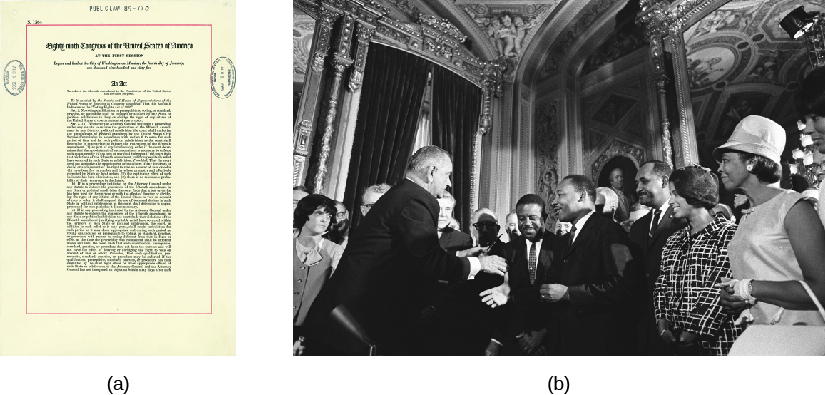

The ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment in 1964 ended poll taxes, but the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1965 had a more profound effect (Figure 7.2). The act protected the rights of minority voters by prohibiting state laws that denied voting rights based on race. The VRA gave the attorney general of the United States authority to order federal examiners to areas with a history of discrimination. These examiners had the power to oversee and monitor voter registration and elections. States found to violate provisions of the VRA were required to get any changes in their election laws approved by the U.S. attorney general or by going through the court system. However, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision, threw out the standards and process of the VRA, effectively gutting the landmark legislation.[4] This decision effectively pushed decision-making and discretion for election policy in VRA states to the state and local level. Several such states subsequently made changes to their voter ID laws and North Carolina changed its plans for how many polling places were available in certain areas. This is the legal avenue though which legislators in scores of U.S. states in 2021 have introduced legislation to make voter registration requirements more stringent and to limit options in terms of voting methods. The extent to which such changes will violate equal protection is unknown in advance, but such changes often do not have a neutral effect.

The effects of the VRA were visible almost immediately. In Mississippi, only 6.7 percent of Black people were registered to vote in 1965; however, by the fall of 1967, nearly 60 percent were registered. Alabama experienced similar effects, with African American registration increasing from 19.3 percent to 51.6 percent. Voter turnout across these two states similarly increased. Mississippi went from 33.9 percent turnout to 53.2 percent, while Alabama increased from 35.9 percent to 52.7 percent between the 1964 and 1968 presidential elections.[5]

Following the implementation of the VRA, many states have sought other methods of increasing voter registration. Several states make registering to vote relatively easy for citizens who have government documentation. Oregon has few requirements for registering and registers many of its voters automatically. North Dakota has no registration at all. In 2002, Arizona was the first state to offer online voter registration, which allowed citizens with a driver’s license to register to vote without any paper application or signature. The system matches the information on the application to information stored at the Department of Motor Vehicles, to ensure each citizen is registering to vote in the right precinct. Citizens without a driver’s license still need to file a paper application. More than eighteen states have moved to online registration or passed laws to begin doing so. The National Conference of State Legislatures estimates, however, that adopting an online voter registration system can initially cost a state between $250,000 and $750,000.[6]

Other states have decided against online registration due to concerns about voter fraud and security. Legislators also argue that online registration makes it difficult to ensure that only citizens are registering and that they are registering in the correct precincts. As technology continues to update other areas of state recordkeeping, online registration may become easier and safer. In some areas, citizens have pressured the states and pushed the process along. A bill to move registration online in Florida stalled for over a year in the legislature, based on security concerns. With strong citizen support, however, it was passed and signed in 2015, despite the governor’s lingering concerns. In other states, such as Texas, both the government and citizens are concerned about identity fraud, so traditional paper registration is still preferred.

HOW DOES SOMEONE REGISTER TO VOTE?

The National Commission on Voting Rights completed a study in September 2015 that found state registration laws can either raise or reduce voter turnout rates, especially among citizens who are young or whose income falls below the poverty line. States with simple voter registration had more registered citizens.[7]

In all states except North Dakota, a citizen wishing to vote must complete an application. Whether the form is online or on paper, the prospective voters will list their name, residency address, and in many cases party identification (with Independent as an option) and affirm that they are competent to vote. States may also have a residency requirement, which establishes how long a citizen must live in a state before becoming eligible to register: it is often thirty days. Beyond these requirements, there may be an oath administered or more questions asked, such as felony convictions. If the application is completely online and the citizen has government documents (e.g., driver’s license or state identification card), the system will compare the application to other state records and accept an online signature or affidavit if everything matches up correctly. Citizens who do not have these state documents are often required to complete paper applications. States without online registration often allow a citizen to fill out an application on a website, but the citizen will receive a paper copy in the mail to sign and mail back to the state.

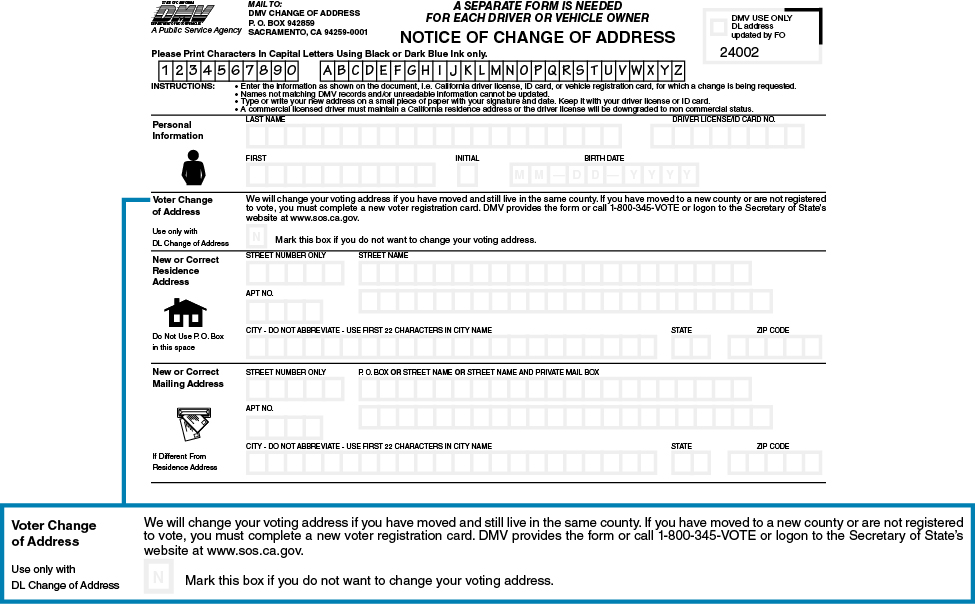

Another aspect of registering to vote is the timeline. States may require registration to take place as much as thirty days before voting, or they may allow same-day registration. Maine first implemented same-day registration in 1973. Fourteen states and the District of Columbia now allow voters to register the day of the election if they have proof of residency, such as a driver’s license or utility bill. Many of the more populous states (e.g., Michigan and Texas), require registration forms to be mailed thirty days before an election. Moving means citizens must re-register or update addresses (Figure 7.3). College students, for example, may have to re-register or update addresses each year as they move. States that use same-day registration had a 4 percent higher voter turnout in the 2012 presidential election than states that did not.[8] Yet another consideration is how far in advance of an election one must apply to change one’s political party affiliation. In states with closed primaries, it is important for voters to be allowed to register into whichever party they prefer. This issue came up during the 2016 presidential primaries in New York, where there is a lengthy timeline for changing your party affiliation.

Some attempts have been made to streamline voter registration. The National Voter Registration Act (1993), often referred to as Motor Voter, was enacted to expedite the registration process and make it as simple as possible for voters. The act required states to allow citizens to register to vote when they sign up for driver’s licenses and Social Security benefits. On each government form, the citizen need only mark an additional box to also register to vote. Unfortunately, while increasing registrations by 7 percent between 1992 and 2012, Motor Voter did not dramatically increase voter turnout.[9] In fact, for two years following the passage of the act, voter turnout decreased slightly.[10] It appears that the main users of the expedited system were those already intending to vote. One study, however, found that preregistration may have a different effect on youth than on the overall voter pool; in Florida, it increased turnout of young voters by 13 percent.[11]

In 2015, Oregon made news when it took the concept of Motor Voter further. When citizens turn eighteen, the state now automatically registers most of them using driver’s license and state identification information. When a citizen moves, the voter rolls are updated when the license is updated. While this policy has been controversial, with some arguing that private information may become public or that Oregon is moving toward mandatory voting, automatic registration is consistent with the state’s efforts to increase registration and turnout.[12]

Oregon’s example offers a possible solution to a recurring problem for states—maintaining accurate voter registration rolls. During the 2000 election, in which George W. Bush won Florida’s electoral votes by a slim majority, attention turned to the state’s election procedures and voter registration rolls. Journalists found that many states, including Florida, had large numbers of phantom voters on their rolls, voters had moved or died but remained on the states’ voter registration rolls.[13] The Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) was passed in order to reform voting across the states and reduce these problems. As part of the Act, states were required to update voting equipment, make voting more accessible to people with disabilities, and maintain computerized voter rolls that could be updated regularly.[14]

Over a decade later, there has been some progress. In Louisiana, voters are placed on ineligible lists if a voting registrar is notified that they have moved or become ineligible to vote. If the voter remains on this list for two general elections, that registration is cancelled. In Oklahoma, the registrar receives a list of deceased residents from the Department of Health.[15] Twenty-nine states now participate in the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program, which allows states to check for duplicate registrations.[16] At the same time, Florida’s use of the federal Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) database has proven to be controversial, because county elections supervisors are allowed to remove voters deemed ineligible to vote.[17]

LINK TO LEARNING

The National Association of Secretaries of State maintains a website that directs users to their state’s information regarding voter registration, identification policies, and polling locations.

WHO IS ALLOWED TO REGISTER?

In order to be eligible to vote in the United States, a person must be a citizen, resident, and eighteen years old. But states often place additional requirements on the right to vote. The most common requirement is that voters must be deemed competent and not currently serving time in jail. Some states enforce more stringent or unusual requirements on citizens who have committed crimes. Kentucky permanently bars felons and ex-felons from voting unless they obtain a pardon from the governor, while Florida, Mississippi, and Nevada allow former felons to apply to have their voting rights restored.[18] Florida previously had a strict policy against felony voting, like Kentucky. However, through a 2018 initiative petition, Florida voters approved a reinstatement of voting rights for felons after their sentences are completed and any financial debt to society paid.[19] On the other end of the spectrum, Vermont does not limit voting based on incarceration unless the crime was election fraud.[20] Maine citizens serving in Maine prisons also may vote in elections.

Beyond those jailed, some citizens have additional expectations placed on them when they register to vote. Wisconsin requires that voters “not wager on an election,” and Vermont citizens must recite the “Voter’s Oath” before they register, swearing to cast votes with a conscience and “without fear or favor of any person.”[21]

GET CONNECTED!

Where to Register?

Across the United States, over twenty million college and university students begin classes each fall, many away from home. The simple act of moving away to college presents a voter registration problem. Elections are local. Each citizen lives in a district with state legislators, city council or other local elected representatives, a U.S. House of Representatives member, and more. State and national laws require voters to reside in their districts, but students are an unusual case. They often hold temporary residency while at school and return home for the summer. Therefore, they have to decide whether to register to vote near campus or vote back in their home district. What are the pros and cons of each option?

Maintaining voter registration back home is legal in most states, assuming a student holds only temporary residency at school. This may be the best plan, because students are likely more familiar with local politicians and issues. But it requires the student to either go home to vote or apply for an absentee ballot. With classes, clubs, work, and more, it may be difficult to remember this task. One study found that students living more than two hours from home were less likely to vote than students living within thirty minutes of campus, which is not surprising.[22]

Registering to vote near campus makes it easier to vote, but it requires an extra step that students may forget (Figure 7.4). And in many states, registration to vote in a November election takes place in October, just when students are acclimating to the semester. They must also become familiar with local candidates and issues, which takes time and effort they may not have. But they will not have to travel to vote, and their vote is more likely to affect their college and local town.

Have you registered to vote in your college area, or will you vote back home? What factors influenced your decision about where to vote?

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 7.1 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Stephen Medvic. 2014. Campaigns and Elections: Players and Processes, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. ↵

- Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915). ↵

- Medvic, Campaigns and Elections. ↵

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013). ↵

- Bernard Grofman, Lisa Handley, and Richard G. Niemi. 1992. Minority Representation and the Quest for Voting Equality. New York: Cambridge University Press, 25. ↵

- “The Canvass,” April 2014, Issue 48, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/states-and-election-reform-the-canvass-april-2014.aspx. ↵

- Tova Wang and Maria Peralta. 22 September 2015. “New Report Released by National Commission on Voting Rights: More Work Needed to Improve Registration and Voting in the U.S.” http://votingrightstoday.org/ncvr/resources/electionadmin. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Royce Crocker, “The National Voter Registration Act of 1993: History, Implementation, and Effects,” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report R40609, September 18, 2013, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40609.pdf. ↵

- “National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789–Present,” http://www.electproject.org/national-1789-present (November 4, 2015). ↵

- John B. Holbein, D. Sunshine Hillygus. 2015. “Making Young Voters: The Impact of Preregistration on Youth Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science (March). doi:10.1111/ajps.12177. ↵

- Russell Berman, “Should Voter Registration Be Automatic?” Atlantic, 20 March 2015; Maria L. La Ganga, “Under New Oregon Law, All Eligible Voters are Registered Unless They Opt Out,” Los Angeles Times, 17 March 2015. ↵

- “’Unusable’ Voter Rolls,” Wall Street Journal, 7 November 2000. ↵

- “One Hundred Seventh Congress of the United States of America at the Second Session,” 23 January 2002. http://www.eac.gov/assets/1/workflow_staging/Page/41.PDF. ↵

- “Voter List Accuracy,”11 February 2014. http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-list-accuracy.aspx ↵

- Brad Bryant and Kay Curtis, eds. December 2013. “Interstate Crosscheck Program Grows,” http://www.kssos.org/forms/communication/canvassing_kansas/dec13.pdf. ↵

- Troy Kinsey, “Proposed Bills Put Greater Scrutiny on Florida’s Voter Purges,” Bay News, 9 November 2015. ↵

- “Felon Voting Rights,” 15 July 2014. http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/felon-voting-rights.aspx. ↵

- Jenni Goldstein, "Florida convicted felons allowed to vote for 1st time in presidential election after completing sentences," ABC News, 25 October 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/convicted-florida-felons-allowed-vote-1st-time-presidential/story?id=73822173. ↵

- Wilson Ring, “Vermont, Maine Only States to Let Inmates Vote,” Associated Press, 22 October 2008. ↵

- “Voter’s Qualifications and Oath,” https://votesmart.org/elections/ballot-measure/1583/voters-qualifications-and-oath#.VjQOJH6rS00 (November 12, 2015). ↵

- Richard Niemi and Michael Hanmer. 2010. “Voter Turnout Among College Students: New Data and a Rethinking of Traditional Theories,” Social Science Quarterly 91, No. 2: 301–323. ↵

the stipulation that citizen must live in a state for a determined period of time before a citizen can register to vote as a resident of that state