Chapter 7: Voting and Elections

Direct Democracy

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the different forms of and reasons for direct democracy

- Summarize the steps needed to place initiatives on a ballot

- Explain why some policies are made by elected representatives and others by voters

The majority of elections in the United States are held to facilitate indirect democracy. Elections allow the people to pick representatives to serve in government and make decisions on the citizens’ behalf. Representatives pass laws, implement taxes, and carry out decisions. Although direct democracy had been used in some of the colonies, the framers of the Constitution granted voters no legislative or executive powers, because they feared the masses would make poor decisions and be susceptible to whims. During the Progressive Era, however, governments began granting citizens more direct political power. States that formed and joined the United States after the Civil War often assigned their citizens some methods of directly implementing laws or removing corrupt politicians. Citizens now use these powers at the ballot to change laws and direct public policy in their states.

DIRECT DEMOCRACY DEFINED

Direct democracy occurs when policy questions go directly to the voters for a decision. These decisions include funding, budgets, candidate removal, candidate approval, policy changes, and constitutional amendments. Not all states allow direct democracy, nor does the United States government.

Direct democracy takes many forms. It may occur locally or statewide. Local direct democracy allows citizens to propose and pass laws that affect local towns or counties. Towns in Massachusetts, for example, may choose to use town meetings, which is a meeting comprised of the town’s eligible voters, to make decisions on budgets, salaries, and local laws.[1]

LINK TO LEARNING

To learn more about what type of direct democracy is practiced in your state, visit the University of Southern California’s Initiative & Referendum Institute. This site also allows you to look up initiatives and measures that have appeared on state ballots.

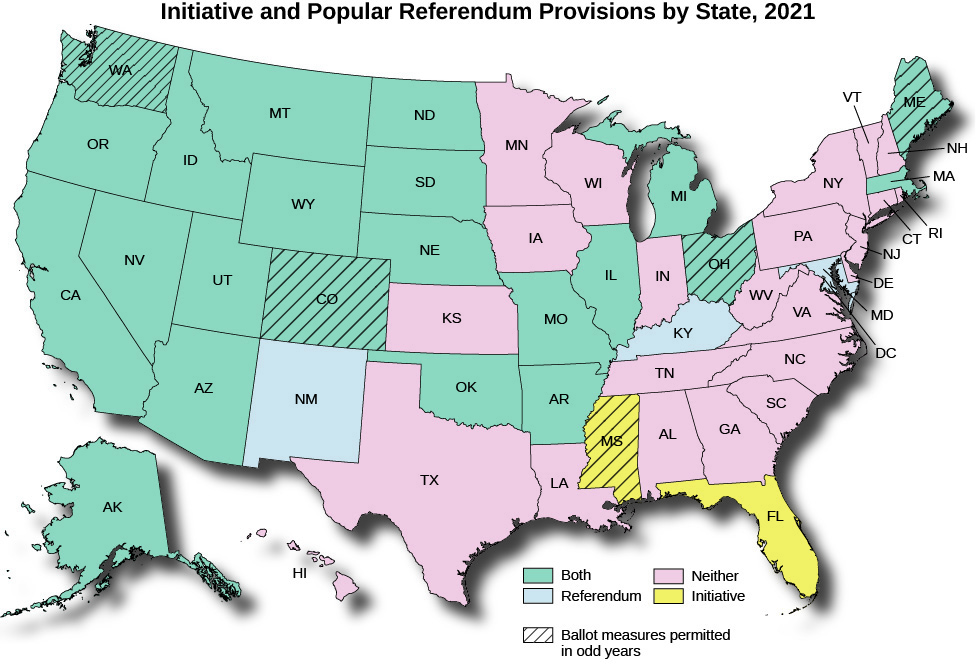

Statewide direct democracy allows citizens to propose and pass laws that affect state constitutions, state budgets, and more. Most states in the western half of the country allow citizens all forms of direct democracy, while most states on the eastern and southern regions allow few or none of these forms (Figure 7.20). States that joined the United States after the Civil War are more likely to have direct democracy, possibly due to the influence of Progressives during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Progressives believed citizens should be more active in government and democracy, a hallmark of direct democracy.

There are three forms of direct democracy used in the United States. A referendum asks citizens to confirm or repeal a decision made by the government. A legislative referendum occurs when a legislature passes a law or a series of constitutional amendments and presents them to the voters to ratify with a yes or no vote. A judicial appointment to a state supreme court may require voters to confirm whether the judge should remain on the bench. Popular referendums occur when citizens petition to place a referendum on a ballot to repeal legislation enacted by their state government. This form of direct democracy gives citizens a limited amount of power, but it does not allow them to overhaul policy or circumvent the government.

The most common form of direct democracy is the initiative, or proposition. An initiative is normally a law or constitutional amendment proposed and passed by the citizens of a state. Initiatives completely bypass the legislatures and governor, but they are subject to review by the state courts if they are not consistent with the state or national constitution. The process to pass an initiative is not easy and varies from state to state. Most states require that a petitioner or the organizers supporting an initiative file paperwork with the state and include the proposed text of the initiative. This allows the state or local office to determine whether the measure is legal, as well as estimate the cost of implementing it. This approval may come at the beginning of the process or after organizers have collected signatures. The initiative may be reviewed by the state attorney general, as in Oregon’s procedures, or by another state official or office. In Utah, the lieutenant governor reviews measures to ensure they are constitutional.

Next, organizers gather registered voters’ signatures on a petition. The number of signatures required is often a percentage of the number of votes from a past election. In California, for example, the required numbers are 5 percent (law) and 8 percent (amendment) of the votes in the last gubernatorial election. This means through 2022, it will take 623,212 signatures to place a law on the ballot and 997,139 to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot.[2]

Once the petition has enough signatures from registered voters, it is approved by a state agency or the secretary of state for placement on the ballot. Signatures are verified by the state or a county elections office to ensure the signatures are valid. If the petition is approved, the initiative is then placed on the next ballot, and the organization campaigns to voters.

While the process is relatively clear, each step can take a lot of time and effort. First, most states place a time limit on the signature collection period. Organizations may have only 150 days to collect signatures, as in California, or as long as two years, as in Arizona. For larger states, the time limit may pose a dilemma if the organization is trying to collect more than 500,000 signatures from registered voters. Second, the state may limit who may circulate the petition and collect signatures. Some states, like Colorado, restrict what a signature collector may earn, while Oregon bans payments to signature-collecting groups. And the minimum number of signatures required affects the number of ballot measures. California had twelve ballot measures on the 2020 general election ballot, because the state requires fewer signatures to get a constitutional amendment or initiative on the ballot than in a state like Oklahoma, where the number of required signatures is higher. In Oklahoma, the required numbers are almost double those of California—8 percent (law) and 15 percent (amendment) of the votes in the last gubernatorial election. California voters may also have an equally high number of local ballot initiatives. For example, a San Francisco voter in the 2016 election had a total of forty-two ballot measures to consider, seventeen at the state level and twenty-five at the city and county level.

Another consideration is that, as we’ve seen, voters in primaries are more ideological and more likely to research the issues. Measures that are complex or require a lot of research, such as a lend-lease bond or changes in the state’s eminent-domain language, may do better on a primary ballot. Measures that deal with social policy, such as laws preventing animal cruelty, may do better on a general election ballot, when more of the general population comes out to vote. Proponents for the amendments or laws will take this into consideration as they plan.

Finally, the recall is one of the more unusual forms of direct democracy; it allows voters to decide whether to remove a government official from office. All states have ways to remove officials, but removal by voters is less common. The recall of California Governor Gray Davis in 2003 and his replacement by Arnold Schwarzenegger is perhaps one of the more famous such recalls. The 2012 attempt by voters in Wisconsin to recall Governor Scott Walker shows how contentious and expensive a recall can be. Walker spent over $60 million in the election to retain his seat.[3]

POLICYMAKING THROUGH DIRECT DEMOCRACY

Politicians are often unwilling to wade into highly political waters if they fear it will harm their chances for reelection. When a legislature refuses to act or change current policy, initiatives allow citizens to take part in the policy process and end the impasse. In Colorado, Amendment 64 allowed the recreational use of marijuana by adults, despite concerns that state law would then conflict with national law. Colorado and Washington’s legalization of recreational marijuana use started a trend, leading to more states adopting similar laws.

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Too Much Democracy?

How much direct democracy is too much? When citizens want one policy direction and government prefers another, who should prevail?

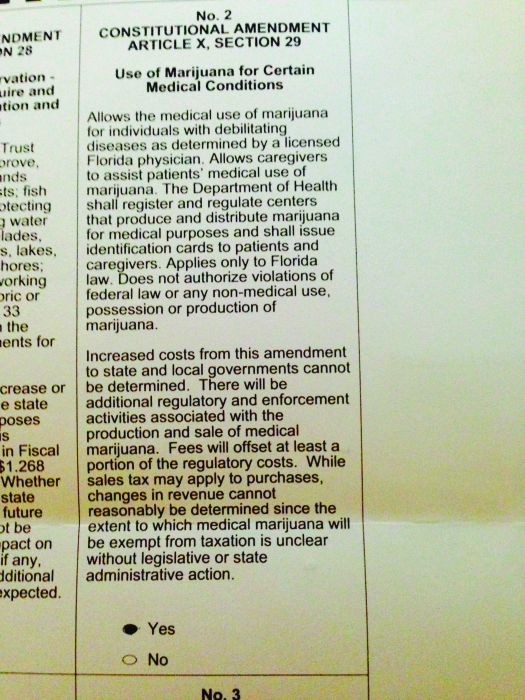

Consider recent laws and decisions about marijuana. California was the first state to allow the use of medical marijuana, after the passage of Proposition 215 in 1996. Just a few years later, however, in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), the Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. government had the authority to criminalize the use of marijuana. In 2009, Attorney General Eric Holder said the federal government would not seek to prosecute patients using marijuana medically, citing limited resources and other priorities. Perhaps emboldened by the national government’s stance, Colorado voters approved recreational marijuana use in 2012. Since then, other states have followed. Forty-two states and the District of Columbia now have laws in place that legalize the use of marijuana to varying degrees. In a number of these cases, the decision was made by voters through initiatives and direct democracy (Figure 7.21).

So where is the problem? First, while citizens of these states believe smoking or consuming marijuana should be legal, the U.S. government does not. The Controlled Substances Act (CSA), passed by Congress in 1970, declares marijuana a dangerous drug and makes its sale a prosecutable act. And despite Holder’s statement, a 2013 memo by James Cole, the deputy attorney general, reminded states that marijuana use is still illegal.[4] But the federal government cannot enforce the CSA on its own; it relies on the states’ help. And while Congress has decided not to prosecute patients using marijuana for medical reasons, it has not waived the Justice Department’s right to prosecute recreational use.[5]

Direct democracy has placed the states and its citizens in an interesting position. States have a legal obligation to enforce state laws and the state constitution, yet they also must follow the laws of the United States. Citizens who use marijuana legally in their state are not using it legally in their country. This leads many to question whether direct democracy gives citizens too much power.

Is it a good idea to give citizens the power to pass laws? Or should this power be subjected to checks and balances, as legislative bills are? Why or why not?

Direct democracy has drawbacks, however. One is that it requires more of voters. Instead of voting based on party, the voter is expected to read and become informed to make smart decisions. Initiatives can fundamentally change a constitution or raise taxes. Recalls remove politicians from office. These are not small decisions. Most citizens, however, do not have the time to perform a lot of research before voting. Given the high number of measures on some ballots, this may explain why many citizens simply skip ballot measures they do not understand. Direct democracy ballot items regularly earn fewer votes than the choice of a governor or president.

When citizens rely on television ads, initiative titles, or advice from others in determining how to vote, they can become confused and make the wrong decisions. In 2008, Californians voted on Proposition 8, titled “Eliminates Rights of Same-Sex Couples to Marry.” A yes vote meant a voter wanted to define marriage as only between a woman and man. Even though the information was clear and the law was one of the shortest in memory, many voters were confused. Some thought of the amendment as the same-sex marriage amendment. In short, some people voted for the initiative because they thought they were voting for same-sex marriage. Others voted against it because they were against same-sex marriage.[6]

Direct democracy also opens the door to special interests funding personal projects. Any group can create an organization to spearhead an initiative or referendum. And because the cost of collecting signatures can be high in many states, signature collection may be backed by interest groups or wealthy individuals wishing to use the initiative to pass pet projects. The 2003 recall of California governor Gray Davis faced difficulties during the signature collection phase, but $2 million in donations by Representative Darrell Issa (R-CA) helped the organization attain nearly one million signatures.[7] Many commentators argued that this example showed direct democracy is not always a process by the people, but rather a process used by the wealthy and business.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 7.5 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Kiku Adatto. May 28, 1990. “The Incredible Shrinking Sound Bite,” New Republic 202, No. 22: 20–23. ↵

- Erik Bucy and Maria Elizabeth Grabe. 2007. “Taking Television Seriously: A Sound and Image Bite Analysis of Presidential Campaign Coverage, 1992–2004,” Journal of Communication 57, No. 4: 652–675. ↵

- Craig Fehrman, “The Incredible Shrinking Sound Bite,” Boston Globe, 2 January 2011, http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2011/01/02/the_incredible_shrinking_sound_bite/. ↵

- “Crossfire: Jon Stewart’s America,” CNN, 15 October 2004, http://www.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0410/15/cf.01.html. ↵

- Paul Begala, “Begala: The day Jon Stewart blew up my show,” CNN, 12 February 2015. ↵

- Pew Research Center: Journalism & Media Staff, “Coverage of the Candidates by Media Sector and Cable Outlet,” 1 November 2012. ↵

- Mark Jurkowitz and Amy Mitchell, "Cable TV and COVID-19: How Americans Perceive the Outbreak and View Media Coverage Differ by Main News Source," Pew Research Center, 1 April 2020, https://www.journalism.org/2020/04/01/cable-tv-and-covid-19-how-americans-perceive-the-outbreak-and-view-media-coverage-differ-by-main-news-source/. ↵

a yes or no vote by citizens on a law or candidate proposed by the state government

law or constitutional amendment proposed and passed by the voters and subject to review by the state courts; also called a proposition

the removal of a politician or government official by the voters