Chapter 17: Foreign Policy

Institutional Relations in Foreign Policy

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the use of shared power in U.S. foreign policymaking

- Explain why presidents lead more in foreign policy than in domestic policy

- Discuss why individual House and Senate members rarely venture into foreign policy

- List the actors who engage in foreign policy

Institutional relationships in foreign policy constitute a paradox. On the one hand, there are aspects of foreign policymaking that necessarily engage multiple branches of government and a multiplicity of actors. Indeed, there is a complexity to foreign policy that is bewildering, in terms of both substance and process. On the other hand, foreign policymaking can sometimes call for nothing more than for the president to make a formal decision, quickly endorsed by the legislative branch. This section will explore the institutional relationships present in U.S. foreign policymaking.

FOREIGN POLICY AND SHARED POWER

While presidents are more empowered by the Constitution in foreign than in domestic policy, they nonetheless must seek approval from Congress on a variety of matters; chief among these is the basic budgetary authority needed to run foreign policy programs. Indeed, most if not all of the foreign policy instruments described earlier in this chapter require interbranch approval to go into effect. Such approval may sometimes be a formality, but it is still important. Even a sole executive agreement often requires subsequent funding from Congress in order to be carried out, and funding calls for majority support from the House and Senate. Presidents lead, to be sure, but they must consult with and engage the Congress on many matters of foreign policy. Presidents must also delegate a great deal in foreign policy to the bureaucratic experts in the foreign policy agencies. Not every operation can be run from the West Wing of the White House.

At bottom, the United States is a separation-of-powers political system with authority divided among executive and legislative branches, including in the foreign policy realm. Table 17.1 shows the formal roles of the president and Congress in conducting foreign policy.

| Roles of the President and Congress in Conducting Foreign Policy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Policy Output | Presidential Role | Congressional Role |

| Public laws | Proposes, signs into law | Proposes, approves for passage |

| Agency reauthorizations | Proposes, signs into law | Approves for passage |

| Foreign policy budget | Proposes, signs into law | Authorizes/appropriates for passage |

| Treaties | Negotiates, ratifies | Senate consents to treaty (two-thirds) |

| Sole executive agreements | Negotiates, approves | None (unless funding is required) |

| Congressional-executive agreements | Negotiates | Approves by majority vote |

| Declaration of war | Proposes | Approves by majority vote |

| Military use of force | Carries out operations at will (sixty days) | Approves for operations beyond sixty days |

| Presidential appointments | Nominates candidates | Senate approves by majority vote |

The main lesson of Table 17.1 is that nearly all major outputs of foreign policy require a formal congressional role in order to be carried out. Foreign policy might be done by executive say-so in times of crisis and in the handful of sole executive agreements that actually pertain to major issues (like the Iran Nuclear Agreement). In general, however, a consultative relationship between the branches in foreign policy is the usual result of their constitutional sharing of power. A president who ignores Congress on matters of foreign policy and does not keep them briefed may find later interactions on other matters more difficult. Probably the most extreme version of this potential dynamic occurred during the Eisenhower presidency. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower used too many executive agreements instead of sending key ones to the Senate as treaties, Congress reacted by considering a constitutional amendment (the Bricker Amendment) that would have altered the treaty process as we know it. Eisenhower understood the message and began to send more agreements through the process as treaties.[1]

Shared power creates an incentive for the branches to cooperate. Even in the midst of a crisis, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, it is common for the president or senior staff to brief congressional leaders in order to keep them up to speed and ensure the country can stand unified on international matters. That said, there are areas of foreign policy where the president has more discretion, such as the operation of intelligence programs, the holding of foreign policy summits, and the mobilization of troops or agents in times of crisis. Moreover, presidents have more power and influence in foreign policymaking than they do in domestic policymaking. It is to that power that we now turn.

THE TWO PRESIDENCIES THESIS

When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the media flock predominately to one actor—the president of the United States—to get the official U.S. position.

In the realm of foreign policy and international relations, the president occupies a leadership spot that is much clearer than in the realm of domestic policy. This dual domestic and international role has been described by the two presidencies thesis. This theory originated with University of California–Berkeley professor Aaron Wildavsky and suggests that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy. Let’s look at the reasoning behind this thesis.

The Constitution names the president as the commander-in-chief of the military, the nominating authority for executive officials and ambassadors, and the initial negotiator of foreign agreements and treaties. The president is the agenda-setter for foreign policy and may move unilaterally in some instances. Beyond the Constitution, presidents were also gradually given more authority to enter into international agreements without Senate consent by using the executive agreement. We saw above that the passage of the War Powers Resolution in 1973, though intended as a statute to rein in executive power and reassert Congress as a check on the president, effectively gave presidents two months to wage war however they wish. Given all these powers, we have good reason to expect presidents to have more influence and be more successful in foreign than in domestic policy.

A second reason for the stronger foreign policy presidency has to do with the informal aspects of power. In some eras, Congress will be more willing to allow the president to be a clear leader and speak for the country. For instance, the Cold War between the Eastern bloc countries (led by the Soviet Union) and the West (led by the United States and Western European allies) prompted many to want a single actor to speak for the United States. A willing Congress allowed the president to take the lead because of urgent circumstances (Figure 17.12). Much of the Cold War also took place when the parties in Congress included more moderates on both sides of the aisle and the environment was less partisan than today. A phrase often heard at that time was, “Partisanship stops at the water’s edge.” This means that foreign policy matters should not be subject to the bitter disagreements seen in party politics.

Does the thesis’s expectation of a more successful foreign policy presidency apply today? While the president still has stronger foreign policy powers than domestic powers, the governing context has changed in two key ways. First, the Cold War ended in 1989 with the demolition of the Berlin Wall, the subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the eventual opening up of Eastern European territories to independence and democracy. These dramatic changes removed the competitive superpower aspect of the Cold War, in which the United States and the USSR were dueling rivals on the world stage. The absence of the Cold War has led to less of a rally-behind-the-president effect in the area of foreign policy.

Second, beginning in the 1980s and escalating in the 1990s, the Democratic and Republican parties began to become polarized in Congress. The moderate members in each party all but disappeared, while more ideologically motivated candidates began to win election to the House and later the Senate. Hence, the Democrats in Congress became more liberal on average, the Republicans became more conservative, and the moderates from each party, who had been able to work together, were edged out. It became increasingly likely that the party opposite the president in Congress might be more willing to challenge his initiatives, whereas in the past it was rare for the opposition party to publicly stand against the president in foreign policy.

Finally, several analysts have tried applying the two presidencies thesis to contemporary presidential-congressional relationships in foreign policy. Is the two presidencies framework still valid in the more partisan post–Cold War era? The answer is mixed. On the one hand, presidents are more successful on foreign policy votes in the House and Senate, on average, than on domestic policy votes. However, the gap has narrowed. Moreover, analysis has also shown that presidents are opposed more often in Congress, even on the foreign policy votes they win.[2] Democratic leaders regularly challenged Republican George W. Bush on the Iraq War and it became common to see the most senior foreign relations committee members of the Republican Party opposing the foreign policy positions of Democratic president Barack Obama. Such challenging of the president by the opposition party simply didn’t happen during the Cold War.

In the Trump administration, there was a distinct shift in foreign policy style. While for some regions, like South America, Trump was content to let the foreign policy bureaucracies proceed as they always had, in certain areas, the president was pivotal in changing the direction of American foreign policy. For example, he stepped away from two key international agreements—the Iran-Nuclear Deal and the Paris climate change accords. Moreover, his actions in Syria were quite unilateral, employing bombing raids unilaterally on two occasions. This approach reflected more of a neoconservative foreign policy approach, similar to Obama’s widespread use of drone strikes.

Therefore, it seems presidents no longer enjoy unanimous foreign policy support as they did in the early 1960s. They have to work harder to get a consensus and are more likely to face opposition. Still, because of their formal powers in foreign policy, presidents are overall more successful on foreign policy than on domestic policy.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF HOUSE AND SENATE MEMBERS

Congress is a bicameral legislative institution with 100 senators serving in the Senate and 435 representatives serving in the House. How interested in foreign policy are typical House and Senate members?

While key White House, executive, and legislative leaders monitor and regularly weigh in on foreign policy matters, the fact is that individual representatives and senators do so much less often. Unless there is a foreign policy crisis, legislators in Congress tend to focus on domestic matters, mainly because there is not much to be gained with their constituents by pursuing foreign policy matters.[3] Domestic policy matters resonate more strongly with the voters at home. A sluggish economy, increasing health care costs, and crime matter more to them than U.S. policy toward North Korea, for example. In an open-ended Gallup poll question from early 2021 about the “most important problem” in the United States, fewer than 10 percent of respondents named a foreign policy topic (and most of those respondents mentioned immigration). These results suggest that foreign policy is not at the top of many voters’ minds. In the end, legislators must be responsive to constituents in order to be good representatives and to achieve reelection.[4]

However, some House and Senate members do wade into foreign policy matters. First, congressional party leaders in the majority and minority parties speak on behalf of their institution and their party on all types of issues, including foreign policy. Some House and Senate members ask to serve on the foreign policy committees, such as the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and the two defense committees (Figure 17.13). These members might have military bases within their districts or states and hence have a constituency reason for being interested in foreign policy. Legislators might also simply have a personal interest in foreign policy matters that drives their engagement in the issue. Finally, they may have ambitions to move into an executive branch position that deals with foreign policy matters, such as secretary of state or defense, CIA director, or even president.

GET CONNECTED!

Let People Know What You Think!

Most House and Senate members do not engage in foreign policy because there is no electoral benefit to doing so. Thus, when citizens become involved, House members and senators will take notice. Research by John Kingdon on roll-call voting and by Richard Hall on committee participation found that when constituents are activated, their interest becomes salient to a legislator and the legislator will respond.[5]

One way you can become active in the foreign policy realm is by writing a letter or e-mail to your House member and/or your two U.S. senators about what you believe the U.S. foreign policy approach in a particular area ought to be. Perhaps you want the United States to work with other countries to protect dolphins from being accidentally trapped in tuna nets. You can also state your position in a letter to the editor of your local newspaper, or post an opinion on the newspaper’s website where a related article or op-ed piece appears. You can share links to news coverage on Facebook or Twitter and consider joining a foreign policy interest group such as Greenpeace.

When you engaged in foreign policy discussion as suggested above, what type of response did you receive?

LINK TO LEARNING

For more information on the two key congressional committees on U.S. foreign policy, visit the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Foreign Affairs Committee websites.

THE MANY ACTORS IN FOREIGN POLICY

A variety of actors carry out the various and complex activities of U.S. foreign policy: White House staff, executive branch staff, and congressional leaders.

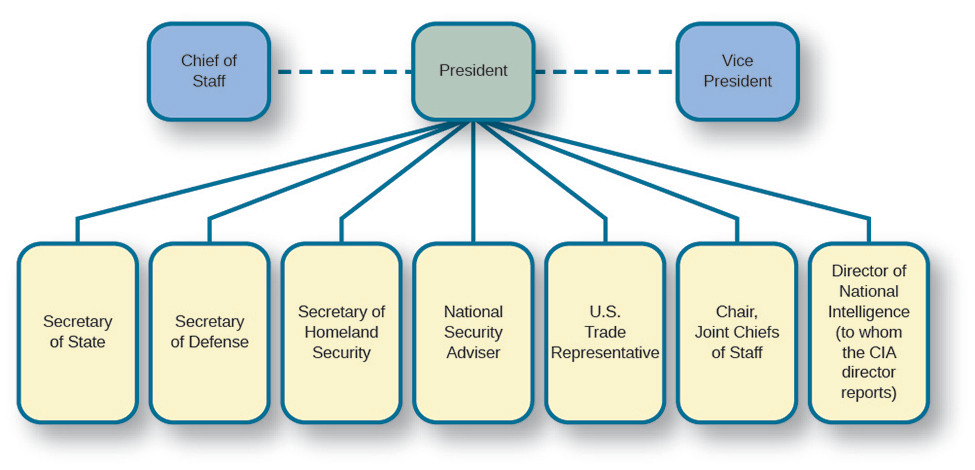

The White House staff members engaged in foreign policy are likely to have very regular contact with the president about their work. The national security advisor heads the president’s National Security Council, a group of senior-level staff from multiple foreign policy agencies, and is generally the president’s top foreign policy advisor. Also reporting to the president in the White House is the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Even more important on intelligence than the CIA director is the director of national intelligence, a position created in the government reorganizations after 9/11, who oversees the entire intelligence community in the U.S. government. The Joint Chiefs of Staff consist of six members, one each from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, plus a chair and vice chair. The chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is the president’s top uniformed military officer. In contrast, the secretary of defense is head of the entire Department of Defense but is a nonmilitary civilian. The U.S. trade representative develops and directs the country’s international trade agenda. Finally, within the Executive Office of the President, another important foreign policy official is the director of the president’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB director develops the president’s yearly budget proposal, including funding for the foreign policy agencies and foreign aid.

In addition to those who work directly in the White House or Executive Office of the President, several important officials work in the broader executive branch and report to the president in the area of foreign policy. Chief among these is the secretary of state. The secretary of state is the nation’s chief diplomat, serves in the president’s cabinet, and oversees the Foreign Service. The secretary of defense, who is the civilian (nonmilitary) head of the armed services housed in the Department of Defense, is also a key cabinet member for foreign policy (as mentioned above). A third cabinet secretary, the secretary of homeland security, is critically important in foreign policy, overseeing the massive Department of Homeland Security (Figure 17.14).

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates

Former secretary of defense Robert Gates served under both Republican and Democratic presidents. First Gates rose through the ranks of the CIA to become the director during the George H. W. Bush administration. He then left government to serve as an academic administrator at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, where he rose to the position of university president. He was able to win over reluctant faculty and advance the university’s position, including increasing the faculty at a time when budgets were in decline in Texas. Then, when Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld resigned, President George W. Bush invited Gates to return to government service as Rumsfeld’s replacement. Gates agreed, serving in that capacity for the remainder of the Bush years and then for several years in the Obama administration before retiring from government service a second time (Figure 17.15). He has generally been seen as thorough, systematic, and fair.

In his memoir, Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War,[6] Secretary Gates takes issue with the actions of both the presidents for whom he worked, but ultimately he praises them for their service and for upholding the right principles in protecting the United States and U.S. military troops. In this and earlier books, Gates discusses the need to have an overarching plan but says plans cannot be too tight or they will fail when things change in the external environment. After leaving politics, Gates served as president of the Boy Scouts of America, where he presided over the change in policy that allowed openly gay scouts and leaders, an issue with which he had had experience as secretary of defense under President Obama. In that role Gates oversaw the end of the military’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.[7]

What do you think about a cabinet secretary serving presidents from two different political parties? Is this is a good idea? Why or why not?

The final group of official key actors in foreign policy are in the U.S. Congress. The Speaker of the House, the House minority leader, and the Senate majority and minority leaders are often given updates on foreign policy matters by the president or the president’s staff. They are also consulted when the president needs foreign policy support or funding. However, the experts in Congress who are most often called on for their views are the committee chairs and the highest-ranking minority members of the relevant House and Senate committees. In the House, that means the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Committee on Armed Services. In the Senate, the relevant committees are the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Armed Services Committee. These committees hold regular hearings on key foreign policy topics, consider budget authorizations, and debate the future of U.S. foreign policy.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 17.3 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Krutz and Peake. Treaty Politics and the Rise of Executive Agreements ↵

- Jon Bond, Richard Fleisher, Stephen Hanna, and Glen S. Krutz. 2000. “The Demise of the. Two Presidencies,” American Politics Quarterly 28, No. 1: 3–25 ↵

- James M. McCormick. 2010. American Foreign Policy and Process, 5th ed. Boston: Wadsworth ↵

- The Gallup Organization, “Most Important Problem,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1675/most-important-problem.aspx (May 12, 2016) ↵

- John W. Kingdon. 1973. Congressmen’s Voting Decisions. New York: Harper & Row; Richard Hall. 1996. Participation in Congress. New Haven, CT: University of Yale Press ↵

- Robert M. Gates. 2015. Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf ↵

- David A. Graham, “Robert Gates, America’s Unlikely Gay-Rights Hero,” The Atlantic, 28 July 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/07/robert-gates-boy-scouts-gay-leaders/399716/ ↵

the thesis by Wildavsky that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy