Chapter 13: The Courts

Judicial Decision-Making and Implementation by the Supreme Court

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how the Supreme Court decides cases and issues opinions

- Identify the various influences on the Supreme Court

- Explain how the judiciary is checked by the other branches of government

The courts are the least covered and least publicly known of the three branches of government. The inner workings of the Supreme Court and its day-to-day operations certainly do not get as much public attention as its rulings, and only a very small number of its announced decisions are enthusiastically discussed and debated. The Court’s 2015 decision on same-sex marriage was the exception, not the rule, since most court opinions are filed away quietly in the United States Reports, sought out mostly by judges, lawyers, researchers, and others with a particular interest in reading or studying them.

Thus, we sometimes envision the justices formally robed and cloistered away in their chambers, unaffected by the world around them, but the reality is that they are not that isolated, and a number of outside factors influence their decisions. Though they lack their own mechanism for enforcement of their rulings and their power remains checked and balanced by the other branches, the effect of the justices’ opinions on the workings of government, politics, and society in the United States is much more significant than the attention they attract might indicate.

*Watch this video to learn more about judicial decisions.

JUDICIAL OPINIONS

Every Court opinion sets precedent for the future. The Supreme Court’s decisions are not always unanimous, however; the published majority opinion, or explanation of the justices’ decision, is the one with which a majority of the nine justices agree. It can represent a vote as narrow as five in favor to four against. A tied vote is rare but can occur at a time of vacancy, absence, or abstention from a case, perhaps where there is a conflict of interest. In the event of a tied vote, the decision of the lower court stands.

Most typically, though, the Court will put forward a majority opinion. If in the majority, the chief justice decides who will write the opinion. If not, then the most senior justice ruling with the majority chooses the writer. Likewise, the most senior justice in the dissenting group can assign a member of that group to write the dissenting opinion; however, any justice who disagrees with the majority may write a separate dissenting opinion. If a justice agrees with the outcome of the case but not with the majority’s reasoning in it, that justice may write a concurring opinion.

Court decisions are released at different times throughout the Court’s term, but all opinions are announced publicly before the Court adjourns for the summer. Some of the most controversial and hotly debated rulings are released near or on the last day of the term and thus are avidly anticipated (Figure 13.12).

LINK TO LEARNING

One of the most prominent writers on judicial decision-making in the U.S. system is Dr. Forrest Maltzman of George Washington University. Maltzman’s articles, chapters, and manuscripts, along with articles by other prominent authors in the field, are downloadable at this site.

INFLUENCES ON THE COURT

Many of the same players who influence whether the Court will grant cert. in a case, discussed earlier in this chapter, also play a role in its decision-making, including law clerks, the solicitor general, interest groups, and the mass media. But additional legal, personal, ideological, and political influences weigh on the Supreme Court and its decision-making process. On the legal side, courts, including the Supreme Court, cannot make a ruling unless they have a case before them, and even with a case, courts must rule on its facts. Although the courts’ role is interpretive, judges and justices are still constrained by the facts of the case, the Constitution, the relevant laws, and the courts’ own precedent.

Justices’ decisions are influenced by how they define their role as a jurist, with some justices believing strongly in judicial activism, or the need to defend individual rights and liberties, and they aim to stop actions and laws by other branches of government that they see as infringing on these rights. A judge or justice who views the role with an activist lens is more likely to use judicial power to broaden personal liberty, justice, and equality. Still others believe in judicial restraint, which leads them to defer decisions (and thus policymaking) to the elected branches of government and stay focused on a narrower interpretation of the Bill of Rights. These justices are less likely to strike down actions or laws as unconstitutional and are less likely to focus on the expansion of individual liberties. While it is typically the case that liberal actions are described as unnecessarily activist, conservative decisions can be activist as well.

Critics of the judiciary often deride activist courts for involving themselves too heavily in matters they believe are better left to the elected legislative and executive branches. However, as Justice Anthony Kennedy has said, “An activist court is a court that makes a decision you don’t like.”[1]

Justices’ personal beliefs and political attitudes also matter in their decision-making. Although we may prefer to believe a justice can leave political ideology or party identification outside the doors of the courtroom, the reality is that a more liberal-thinking judge may tend to make more liberal decisions and a more conservative-leaning judge may tend toward more conservative ones. Although this is not true 100 percent of the time, and an individual’s decisions are sometimes a cause for surprise, the influence of ideology is real, and at a minimum, it often guides presidents to aim for nominees who mirror their own political or ideological image. It is likely not possible to find a potential justice who is completely apolitical.

And the courts themselves are affected by another “court”—the court of public opinion. Though somewhat isolated from politics and the volatility of the electorate, justices may still be swayed by special-interest pressure, the leverage of elected or other public officials, the mass media, and the general public. As times change and the opinions of the population change, the court’s interpretation is likely to keep up with those changes, lest the courts face the danger of losing their own relevance.

Take, for example, rulings on sodomy laws: In 1986, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the State of Georgia’s ban on sodomy,[2] but it reversed its decision seventeen years later, invalidating sodomy laws in Texas and thirteen other states.[3] No doubt the Court considered what had been happening nationwide: In the 1960s, sodomy was banned in all the states. By 1986, that number had been reduced by about half. By 2002, thirty-six states had repealed their sodomy laws, and most states were only selectively enforcing them. Changes in state laws, along with an emerging LGBTQ movement, no doubt swayed the Court and led it to the reversal of its earlier ruling with the 2003 decision, Lawrence v. Texas (Figure 13.13).[4]This decision was an especially important one because it meant all prior and existing laws that formally made same-sex relationships illegal were null and void.

Heralded by advocates of gay rights as important progress toward greater equality, the ruling in Lawrence v. Texas illustrates that the Court is willing to reflect upon what is going on in the world. Even with their heavy reliance on precedent and reluctance to throw out past decisions, justices are not completely inflexible and do tend to change and evolve with the times.

GET CONNECTED!

The Importance of Jury Duty

Since judges and justices are not elected, we sometimes consider the courts removed from the public; however, this is not always the case, and there are times when average citizens may get involved with the courts firsthand as part of their decision-making process at either the state or federal levels. At some point, if you haven’t already been called, you may receive a summons for jury duty from your local court system. You may be asked to serve on federal jury duty, such as U.S. district court duty or federal grand jury duty, but service at the local level, in the state court system, is much more common.

While your first reaction may be to start planning a way to get out of it, participating in jury service is vital to the operation of the judicial system, because it provides individuals in court the chance to be heard and to be tried fairly by a group of their peers. And jury duty has benefits for those who serve as well. You will no doubt come away better informed about how the judicial system works and ready to share your experiences with others. Who knows? You might even get an unexpected surprise, as some citizens in Dallas, Texas did recently when former President George W. Bush showed up to serve jury duty with them.

Have you ever been called to jury duty? Describe your experience. What did you learn about the judicial process? What advice would you give to someone called to jury duty for the first time? If you’ve never been called to jury duty, what questions do you have for those who have?

THE COURTS AND THE OTHER BRANCHES OF GOVERNMENT

Both the executive and legislative branches check and balance the judiciary in many different ways. The president can leave a lasting imprint on the bench through nominations, even long after leaving office. The president may also influence the Court through the solicitor general’s involvement or through the submission of amicus briefs in cases in which the United States is not a party.

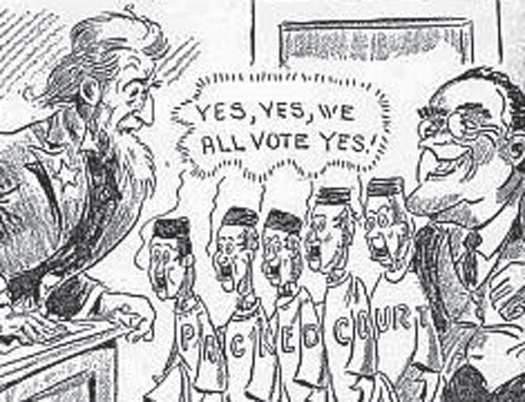

President Franklin D. Roosevelt even attempted to stack the odds in his favor in 1937, with a “court-packing scheme” in which he tried to get a bill passed through Congress that would have reorganized the judiciary and enabled him to appoint up to six additional judges to the high court (Figure 13.14). The bill never passed, but other presidents have also been accused of trying similar moves at different courts in the federal system.

Likewise, Congress has checks on the judiciary. It retains the power to modify the federal court structure and its appellate jurisdiction, and the Senate may accept or reject presidential nominees to the federal courts. Faced with a court ruling that overturns one of its laws, Congress may rewrite the law or even begin a constitutional amendment process.

But the most significant check on the Supreme Court is executive and legislative leverage over the implementation and enforcement of its rulings. This process is called judicial implementation. While it is true that courts play a major role in policymaking, they have no mechanism to make their rulings a reality. Remember it was Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 78 who remarked that the courts had “neither force nor will, but merely judgment.” And even years later, when the 1832 Supreme Court ruled the State of Georgia’s seizing of Native American lands unconstitutional,[5] President Andrew Jackson is reported to have said, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it,” and the Court’s ruling was basically ignored.[6] Abraham Lincoln, too, famously ignored Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s order finding unconstitutional Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus rights in 1861, early in the Civil War. Thus, court rulings matter only to the extent they are heeded and followed.

The Court relies on the executive to implement or enforce its decisions and on the legislative branch to fund them. As the Jackson and Lincoln stories indicate, presidents may simply ignore decisions of the Court, and Congress may withhold funding needed for implementation and enforcement. Fortunately for the courts, these situations rarely happen, and the other branches tend to provide support rather than opposition. In general, presidents have tended to see it as their duty to both obey and enforce Court rulings, and Congress seldom takes away the funding needed for the president to do so.

For example, in 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower called out the military by executive order to enforce the Supreme Court’s order to racially integrate the public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas. Eisenhower told the nation: “Whenever normal agencies prove inadequate to the task and it becomes necessary for the executive branch of the federal government to use its powers and authority to uphold federal courts, the president’s responsibility is inescapable.”[7]Executive Order 10730 nationalized the Arkansas National Guard to enforce desegregation because the governor refused to use the state National Guard troops to protect the Black students trying to enter the school (Figure 13.15).

So what becomes of court decisions is largely due to their credibility, their viability, and the assistance given by the other branches of government. It is also somewhat a matter of tradition and the way the United States has gone about its judicial business for more than two centuries. Although not everyone agrees with the decisions made by the Court, rulings are generally accepted and followed, and the Court is respected as the key interpreter of the laws and the Constitution. Over time, its rulings have become yet another way policy is legitimately made and justice more adequately served in the United States.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 13.5 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Matt Sedensky. “Justice questions way court nominees are grilled.” The Associated Press. May 14, 2010. http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2010/05/14/justice_questions_way_court_nominees_are_grilled/ ↵

- Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986) ↵

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) ↵

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) ↵

- Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832). ↵

- “Court History.” Supreme Court History: The First Hundred Years. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/history2.html (March 1, 2016) ↵

- Dwight D. Eisenhower. “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock.” Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Eisenhower, Dwight D., The American Presidency Project. September 24, 1957. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=10909. ↵

an opinion of the Court with which more than half the nine justices agree

an opinion written by a justice who disagrees with the majority opinion of the Court

an opinion written by a justice who agrees with the Court’s majority opinion but has different reasons for doing so

a judicial philosophy in which a justice is more likely to overturn decisions or rule actions by the other branches unconstitutional, especially in an attempt to broaden individual rights and liberties

a judicial philosophy in which a justice is more likely to let stand the decisions or actions of the other branches of government