Chapter 11: Congress

House and Senate Organizations

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the division of labor in the House and in the Senate

- Describe the way congressional committees develop and advance legislation

Not all the business of Congress involves bickering, political infighting, government shutdowns, and Machiavellian maneuvering. Congress does actually get work done. Traditionally, it does this work in a very methodical way. In this section, we will explore how Congress functions at the leadership and committee levels. We will learn how the party leadership controls their conferences and how the many committees within Congress create legislation that can then be moved forward or die on the floor.

*Watch this video to learn more about congressional committees.

PARTY LEADERSHIP

The party leadership in Congress controls the actions of Congress. Leaders are elected by the two-party conferences in each chamber. In the House of Representatives, these are the House Democratic Conference and the House Republican Conference. These conferences meet regularly and separately not only to elect their leaders but also to discuss important issues and strategies for moving policy forward. Based on the number of members in each conference, one conference becomes the majority conference and the other becomes the minority conference. Independents like Senator Bernie Sanders will typically join one or the other major party conference, as a matter of practicality and often based on ideological affinity. Without the membership to elect their own leadership, independents would have a very difficult time getting things done in Congress unless they had a relationship with the leaders.

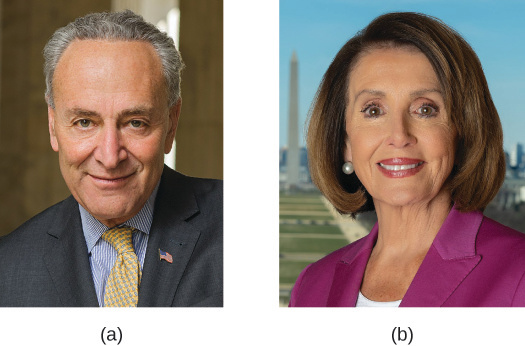

Despite the power of the conferences, however, the most important leadership position in the House is actually elected by the entire body of representatives. This position is called the Speaker of the House and is the only House officer mentioned in the Constitution. The Constitution does not require the Speaker to be a member of the House, although to date, all fifty-four Speakers have been. The Speaker is the presiding officer, the administrative head of the House, the partisan leader of the majority party in the House, and an elected representative of a single congressional district (Figure 11.16). As a testament to the importance of the Speaker, since 1947, the holder of this position has been second in line to succeed the president in an emergency, after the vice president.

The Speaker serves until their party loses, or until the Speaker is voted out of the position or chooses to step down. Republican Speaker John Boehner became the latest Speaker to walk away from the position when it appeared his position was in jeopardy. This event shows how the party conference (or caucus) oversees the leadership as much as, if not more than, the leadership oversees the party membership in the chamber. The Speaker is invested with quite a bit of power, such as the ability to assign bills to committees and decide when a bill will be presented to the floor for a vote. The Speaker also rules on House procedures, often delegating authority for certain duties to other members. He or she appoints members and chairs to committees, creates select committees to fulfill a specific purpose and then disband, and can even select a member to be speaker pro tempore, who acts as Speaker in the Speaker’s absence. Finally, when the Senate joins the House in a joint session, the Speaker presides over these sessions, because they are usually held in the House of Representatives.

Below the Speaker, the majority and minority conferences each elect two leadership positions arranged in hierarchical order. At the top of the hierarchy are the floor leaders of each party. These are generally referred to as the majority and minority leaders. The minority leader has a visible if not always a powerful position. As the official leader of the opposition, they technically hold the rank closest to that of the Speaker, makes strategy decisions, and attempts to keep order within the minority. However, the majority rules the day in the House, like a cartel. On the majority side, because it holds the speakership, the majority leader also has considerable power. Historically, moreover, the majority leader tends to be in the best position to assume the speakership when the current Speaker steps down.

Below these leaders are the two party’s respective whips. A whip’s job, as the name suggests, is to whip up votes and otherwise enforce party discipline. Whips make the rounds in Congress, telling members the position of the leadership and the collective voting strategy, and sometimes they wave various carrots and sticks in front of recalcitrant members to bring them in line. The remainder of the leadership positions in the House include a handful of chairs and assistantships.

Like the House, the Senate also has majority and minority leaders and whips, each with duties very similar to those of their counterparts in the House. Unlike the House, however, the Senate doesn’t have a Speaker. The duties and powers held by the Speaker in the House fall to the majority leader in the Senate. Another difference is that, according to the U.S. Constitution, the Senate’s president is actually the elected vice president of the United States, but may vote only in case of a tie. Apart from this and very few other exceptions, the president of the Senate does not actually operate in the Senate. Instead, the Constitution allows for the Senate to choose a president pro tempore—usually the most senior senator of the majority party—who presides over the Senate. Despite the title, the job is largely a formal and powerless role. The real power in the Senate is in the hands of the majority leader (Figure 11.16) and the minority leader. Like the Speaker of the House, the majority leader is the chief spokesperson for the majority party, but, unlike in the House, does not run the floor alone. Because of the traditions of unlimited debate and the filibuster, the majority and minority leaders often occupy the floor together in an attempt to keep things moving along. At times, their interactions are intense and partisan, but for the Senate to get things done, they must cooperate to get the sixty votes needed to run this super-majority legislative institution.

*Watch this video to learn more about congressional leadership.

THE COMMITTEE SYSTEM

With 535 members in Congress and a seemingly infinite number of domestic, international, economic, agricultural, regulatory, criminal, and military issues to deal with at any given moment, the two chambers must divide their work based on specialization. Congress does this through the committee system. Specialized committees (or subcommittees) in both the House and the Senate are where bills originate and most of the work that sets the congressional agenda takes place. Committees are roughly approximate to a bureaucratic department in the executive branch. There are well over two hundred committees, subcommittees, select committees, and joint committees in the Congress. The core committees are called standing committees. There are twenty standing committees in the House and sixteen in the Senate (Table 11.2).

| Congressional Standing and Permanent Select Committees | |

|---|---|

| House of Representatives | Senate |

| Agriculture | Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

| Appropriations | Appropriations |

| Armed Services | Armed Services |

| Budget | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Education and Labor | Budget |

| Energy and Commerce | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Ethics | Energy and Natural Resources |

| Financial Services | Environment and Public Works |

| Foreign Affairs | Ethics (select) |

| Homeland Security | Finance |

| House Administration | Foreign Relations |

| Intelligence (select) | Health, Education, Labor and Pensions |

| Judiciary | Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

| Natural Resources | Indian Affairs |

| Oversight and Government Reform | Intelligence (select) |

| Rules | Judiciary |

| Science, Space, and Technology | Rules and Administration |

| Small Business | Small Business and Entrepreneurship |

| Transportation and Infrastructure | Veterans’ Affairs |

| Veterans’ Affairs | |

| Ways and Means | |

Members of both parties compete for positions on various committees. These positions are typically filled by majority and minority members to roughly approximate the ratio of majority to minority members in the respective chambers, although committees are chaired by members of the majority party. Committees and their chairs have a lot of power in the legislative process, including the ability to stop a bill from going to the floor (the full chamber) for a vote. Indeed, most bills die in committee. But when a committee is eager to develop legislation, it takes a number of methodical steps. It will reach out to relevant agencies for comment on resolutions to the problem at hand, such as by holding hearings with experts to collect information. In the Senate, committee hearings are also held to confirm presidential appointments (Figure 11.17). After the information has been collected, the committee meets to discuss amendments and legislative language. Finally, the committee will send the bill to the full chamber along with a committee report. The report provides the majority opinion about why the bill should be passed, a minority view to the contrary, and estimates of the proposed law’s cost and impact.

Four types of committees exist in the House and the Senate. The first is the standing, or permanent, committee. This committee is the first call for proposed bills, fewer than 10 percent of which are reported out of committee to the floor. The second type is the joint committee. Joint committee members are appointed from both the House and the Senate, and are charged with exploring a few key issues, such as the economy and taxation. However, joint committees have no bill-referral authority whatsoever—they are informational only. A conference committee is used to reconcile different bills passed in both the House and the Senate. The conference committees are appointed on an ad hoc basis as necessary when a bill passes the House and Senate in different forms. Conference committees are sometimes skipped in the interest of expedience, in which one of the chambers relents to the other chamber. For example, the House demurred to the Senate over the Affordable Care Act instead of going to battle in a conference committee. Still, conference committees are the norm on most major pieces of legislation. A recent example is the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, passed in December. Finally, ad hoc, special, or select committees are temporary committees set up to address specific topics. These types of committees often conduct special investigations, such as on aging or ethics.

Committee hearings can become politically driven public spectacles. Consider the House Select Committee on Benghazi, the committee assembled by Republicans to further investigate the 2011 attacks on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya. This prolonged investigation became particularly partisan as Republicans focused on then-secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who was running for the presidency at the time. In two multi-hour hearings in which Secretary Clinton was the only witness, Republicans tended to grandstand in the hopes of gaining political advantage or tripping her up, while Democrats tended to use their time to ridicule Republicans (Figure 11.18).[1] In the end, the long hearings uncovered little more than the elevated state of partisanship in the House, which had scarcely been a secret before.

Members of Congress bring to their roles a variety of specific experiences, interests, and levels of expertise, and try to match these to committee positions. For example, House members from states with large agricultural interests will typically seek positions on the Agriculture Committee. Senate members with a background in banking or finance may seek positions on the Senate Finance Committee. Members can request these positions from their chambers’ respective leadership, and the leadership also selects the committee chairs.

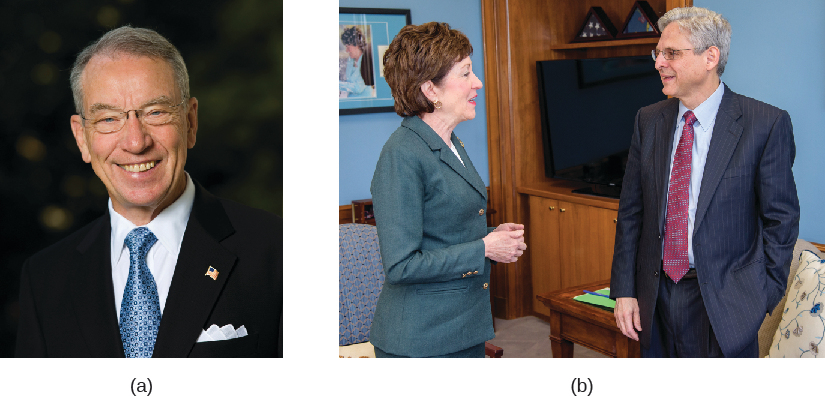

Committee chairs are very powerful. They control the committee’s budget and choose when the committee will meet, when it will hold hearings, and even whether it will consider a bill (Figure 11.19). A chair can convene a meeting when members of the minority are absent or adjourn a meeting when things are not progressing as the majority leadership wishes. Chairs can hear a bill even when the rest of the committee objects. They do not remain in these powerful positions indefinitely, however. In the House, rules prevent committee chairs from serving more than six consecutive years and from serving as the chair of a subcommittee at the same time. A senator may serve only six years as chair of a committee but may, in some instances, also serve as a chair or ranking member of another committee.

Because the Senate is much smaller than the House, senators hold more committee assignments than House members. There are sixteen standing committees in the Senate, and each position must be filled. In contrast, in the House, with 435 members and only twenty standing committees, committee members have time to pursue a more in-depth review of a policy. House members historically defer to the decisions of committees, while senators tend to view committee decisions as recommendations, often seeking additional discussion that could lead to changes.

LINK TO LEARNING

Take a look at the scores of committees in the House and Senate. The late House Speaker Tip O’Neill once quipped that if you didn’t know a new House member’s name, you could just call him Mr. Chairperson.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 11.4 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary, and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- “Congress and the Public,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/congress-public.aspx (May 15, 2016). ↵