Chapter 28 Special Relativity

28.3 Length Contraction

Summary

- Describe proper length.

- Calculate length contraction.

- Explain why we don’t notice these effects at everyday scales.

Have you ever driven on a road that seems like it goes on forever? If you look ahead, you might say you have about 10 km left to go. Another traveler might say the road ahead looks like it’s about 15 km long. If you both measured the road, however, you would agree. Traveling at everyday speeds, the distance you both measure would be the same. You will read in this section, however, that this is not true at relativistic speeds. Close to the speed of light, distances measured are not the same when measured by different observers.

Proper Length

One thing all observers agree upon is relative speed. Even though clocks measure different elapsed times for the same process, they still agree that relative speed, which is distance divided by elapsed time, is the same. This implies that distance, too, depends on the observer’s relative motion. If two observers see different times, then they must also see different distances for relative speed to be the same to each of them.

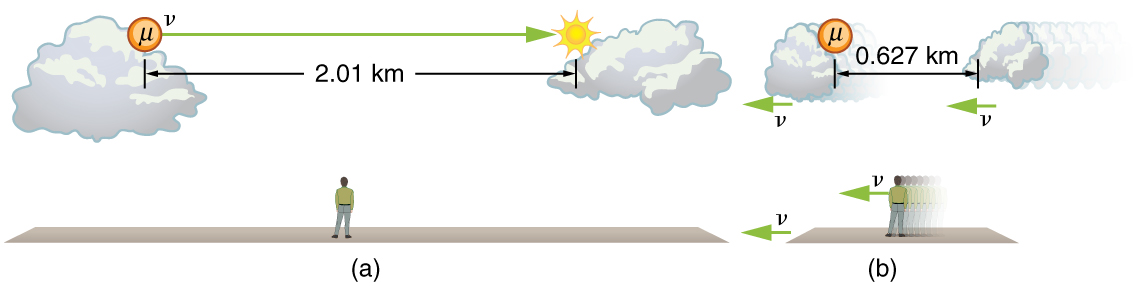

The muon discussed in Chapter 28.2 Example 1 illustrates this concept. To an observer on the Earth, the muon travels at ![]() for

for ![]() from the time it is produced until it decays. Thus it travels a distance

from the time it is produced until it decays. Thus it travels a distance

relative to the Earth. In the muon’s frame of reference, its lifetime is only 2.20μs2.20μs. It has enough time to travel only

The distance between the same two events (production and decay of a muon) depends on who measures it and how they are moving relative to it.

Proper Length

Proper length ![]() is the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points.

is the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points.

The Earth-bound observer measures the proper length ![]() , because the points at which the muon is produced and decays are stationary relative to the Earth. To the muon, the Earth, air, and clouds are moving, and so the distance

, because the points at which the muon is produced and decays are stationary relative to the Earth. To the muon, the Earth, air, and clouds are moving, and so the distance ![]() it sees is not the proper length.

it sees is not the proper length.

Length Contraction

To develop an equation relating distances measured by different observers, we note that the velocity relative to the Earth-bound observer in our muon example is given by

The time relative to the Earth-bound observer is ![]() , since the object being timed is moving relative to this observer. The velocity relative to the moving observer is given by

, since the object being timed is moving relative to this observer. The velocity relative to the moving observer is given by

The moving observer travels with the muon and therefore observes the proper time ![]() . The two velocities are identical; thus,

. The two velocities are identical; thus,

We know that ![]() . Substituting this equation into the relationship above gives

. Substituting this equation into the relationship above gives

Substituting for ![]() gives an equation relating the distances measured by different observers.

gives an equation relating the distances measured by different observers.

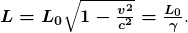

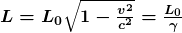

Length Contraction

Length contraction [/latex]latex\boldsymbol{L}[/latex] is the shortening of the measured length of an object moving relative to the observer’s frame.

If we measure the length of anything moving relative to our frame, we find its length ![]() to be smaller than the proper length

to be smaller than the proper length ![]() that would be measured if the object were stationary. For example, in the muon’s reference frame, the distance between the points where it was produced and where it decayed is shorter. Those points are fixed relative to the Earth but moving relative to the muon. Clouds and other objects are also contracted along the direction of motion in the muon’s reference frame.

that would be measured if the object were stationary. For example, in the muon’s reference frame, the distance between the points where it was produced and where it decayed is shorter. Those points are fixed relative to the Earth but moving relative to the muon. Clouds and other objects are also contracted along the direction of motion in the muon’s reference frame.

Example 1: Calculating Length Contraction: The Distance between Stars Contracts when You Travel at High Velocity

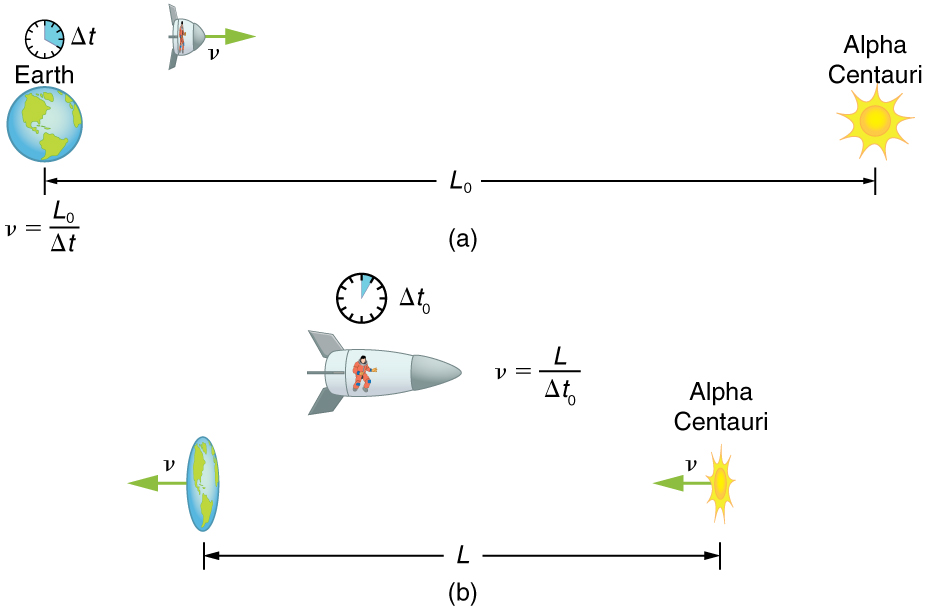

Suppose an astronaut, such as the twin discussed in Chapter 28.2 Simultaneity and Time Dilation, travels so fast that ![]() . (a) She travels from the Earth to the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, 4.300 light years (ly) away as measured by an Earth-bound observer. How far apart are the Earth and Alpha Centauri as measured by the astronaut? (b) In terms of

. (a) She travels from the Earth to the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, 4.300 light years (ly) away as measured by an Earth-bound observer. How far apart are the Earth and Alpha Centauri as measured by the astronaut? (b) In terms of ![]() , what is her velocity relative to the Earth? You may neglect the motion of the Earth relative to the Sun. (See Figure 3.)

, what is her velocity relative to the Earth? You may neglect the motion of the Earth relative to the Sun. (See Figure 3.)

Strategy

First note that a light year (ly) is a convenient unit of distance on an astronomical scale—it is the distance light travels in a year. For part (a), note that the 4.300 ly distance between the Alpha Centauri and the Earth is the proper distance ![]() , because it is measured by an Earth-bound observer to whom both stars are (approximately) stationary. To the astronaut, the Earth and the Alpha Centauri are moving by at the same velocity, and so the distance between them is the contracted length

, because it is measured by an Earth-bound observer to whom both stars are (approximately) stationary. To the astronaut, the Earth and the Alpha Centauri are moving by at the same velocity, and so the distance between them is the contracted length ![]() . In part (b), we are given

. In part (b), we are given ![]() , and so we can find

, and so we can find ![]() by rearranging the definition of

by rearranging the definition of ![]() to express

to express ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

.

Solution for (a)

- Identify the knowns.

;

;

- Identify the unknown.

- Choose the appropriate equation.

- Rearrange the equation to solve for the unknown.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com $\begin{array}{r @{{}={}}l} \boldsymbol{L} & \boldsymbol{\frac{L_0}{\gamma}} \\[1em] & \boldsymbol{\frac{4.300 \;\textbf{ly}}{30.00}} \\[1em] & \boldsymbol{0.1433 \;\textbf{ly}} \end{array}$](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-f3a9d84ca9a60def40160c29cca2ffd4_l3.png)

Solution for (b)

- Identify the known.

- Identify the unknown.

in terms of

in terms of

- Choose the appropriate equation.

- Rearrange the equation to solve for the unknown.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com $\begin{array}{r @{{}={}}l}\boldsymbol{\gamma} & \boldsymbol{\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}}} \\[1em] \boldsymbol{30.00} & \boldsymbol{\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}}} \end{array}$](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-0fc23f0016952a54bde45d69b6bb0b9b_l3.png)

Squaring both sides of the equation and rearranging terms gives

so that

and

Taking the square root, we find

which is rearranged to produce a value for the velocity

Discussion

First, remember that you should not round off calculations until the final result is obtained, or you could get erroneous results. This is especially true for special relativity calculations, where the differences might only be revealed after several decimal places. The relativistic effect is large here (![]() ), and we see that

), and we see that ![]() is approaching (not equaling) the speed of light. Since the distance as measured by the astronaut is so much smaller, the astronaut can travel it in much less time in her frame.

is approaching (not equaling) the speed of light. Since the distance as measured by the astronaut is so much smaller, the astronaut can travel it in much less time in her frame.

People could be sent very large distances (thousands or even millions of light years) and age only a few years on the way if they traveled at extremely high velocities. But, like emigrants of centuries past, they would leave the Earth they know forever. Even if they returned, thousands to millions of years would have passed on the Earth, obliterating most of what now exists. There is also a more serious practical obstacle to traveling at such velocities; immensely greater energies than classical physics predicts would be needed to achieve such high velocities. This will be discussed in Chapter 28.6 Relativistic Energy.

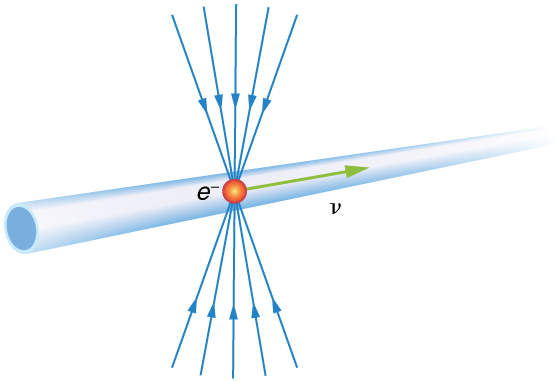

Why don’t we notice length contraction in everyday life? The distance to the grocery shop does not seem to depend on whether we are moving or not. Examining the equation ![]() , we see that at low velocities (

, we see that at low velocities (![]() ) the lengths are nearly equal, the classical expectation. But length contraction is real, if not commonly experienced. For example, a charged particle, like an electron, traveling at relativistic velocity has electric field lines that are compressed along the direction of motion as seen by a stationary observer. (See Figure 4.) As the electron passes a detector, such as a coil of wire, its field interacts much more briefly, an effect observed at particle accelerators such as the 3 km long Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC). In fact, to an electron traveling down the beam pipe at SLAC, the accelerator and the Earth are all moving by and are length contracted. The relativistic effect is so great than the accelerator is only 0.5 m long to the electron. It is actually easier to get the electron beam down the pipe, since the beam does not have to be as precisely aimed to get down a short pipe as it would down one 3 km long. This, again, is an experimental verification of the Special Theory of Relativity.

) the lengths are nearly equal, the classical expectation. But length contraction is real, if not commonly experienced. For example, a charged particle, like an electron, traveling at relativistic velocity has electric field lines that are compressed along the direction of motion as seen by a stationary observer. (See Figure 4.) As the electron passes a detector, such as a coil of wire, its field interacts much more briefly, an effect observed at particle accelerators such as the 3 km long Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC). In fact, to an electron traveling down the beam pipe at SLAC, the accelerator and the Earth are all moving by and are length contracted. The relativistic effect is so great than the accelerator is only 0.5 m long to the electron. It is actually easier to get the electron beam down the pipe, since the beam does not have to be as precisely aimed to get down a short pipe as it would down one 3 km long. This, again, is an experimental verification of the Special Theory of Relativity.

Check Your Understanding

1: A particle is traveling through the Earth’s atmosphere at a speed of ![]() . To an Earth-bound observer, the distance it travels is 2.50 km. How far does the particle travel in the particle’s frame of reference?

. To an Earth-bound observer, the distance it travels is 2.50 km. How far does the particle travel in the particle’s frame of reference?

Summary

- All observers agree upon relative speed.

- Distance depends on an observer’s motion. Proper length

is the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points. Earth-bound observers measure proper length when measuring the distance between two points that are stationary relative to the Earth.

is the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points. Earth-bound observers measure proper length when measuring the distance between two points that are stationary relative to the Earth. - Length contraction

is the shortening of the measured length of an object moving relative to the observer’s frame:

is the shortening of the measured length of an object moving relative to the observer’s frame:

Conceptual Questions

1: To whom does an object seem greater in length, an observer moving with the object or an observer moving relative to the object? Which observer measures the object’s proper length?

2: Relativistic effects such as time dilation and length contraction are present for cars and airplanes. Why do these effects seem strange to us?

3: Suppose an astronaut is moving relative to the Earth at a significant fraction of the speed of light. (a) Does he observe the rate of his clocks to have slowed? (b) What change in the rate of Earth-bound clocks does he see? (c) Does his ship seem to him to shorten? (d) What about the distance between stars that lie on lines parallel to his motion? (e) Do he and an Earth-bound observer agree on his velocity relative to the Earth?

Problems & Exercises

1: A spaceship, 200 m long as seen on board, moves by the Earth at ![]() . What is its length as measured by an Earth-bound observer?

. What is its length as measured by an Earth-bound observer?

2: How fast would a 6.0 m-long sports car have to be going past you in order for it to appear only 5.5 m long?

3: (a) How far does the muon in Chapter 28.2 Example 1 travel according to the Earth-bound observer? (b) How far does it travel as viewed by an observer moving with it? Base your calculation on its velocity relative to the Earth and the time it lives (proper time). (c) Verify that these two distances are related through length contraction ![]() .

.

4: (a) How long would the muon in Chapter 28.2 Example 1 have lived as observed on the Earth if its velocity was ![]() ? (b) How far would it have traveled as observed on the Earth? (c) What distance is this in the muon’s frame?

? (b) How far would it have traveled as observed on the Earth? (c) What distance is this in the muon’s frame?

5: (a) How long does it take the astronaut in Example 1 to travel 4.30 ly at ![]() (as measured by the Earth-bound observer)? (b) How long does it take according to the astronaut? (c) Verify that these two times are related through time dilation with

(as measured by the Earth-bound observer)? (b) How long does it take according to the astronaut? (c) Verify that these two times are related through time dilation with ![]() as given.

as given.

6: (a) How fast would an athlete need to be running for a 100-m race to look 100 yd long? (b) Is the answer consistent with the fact that relativistic effects are difficult to observe in ordinary circumstances? Explain.

7: Unreasonable Results

(a) Find the value of ![]() for the following situation. An astronaut measures the length of her spaceship to be 25.0 m, while an Earth-bound observer measures it to be 100 m. (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

for the following situation. An astronaut measures the length of her spaceship to be 25.0 m, while an Earth-bound observer measures it to be 100 m. (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

8: Unreasonable Results

A spaceship is heading directly toward the Earth at a velocity of ![]() . The astronaut on board claims that he can send a canister toward the Earth at

. The astronaut on board claims that he can send a canister toward the Earth at ![]() relative to the Earth. (a) Calculate the velocity the canister must have relative to the spaceship. (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

relative to the Earth. (a) Calculate the velocity the canister must have relative to the spaceship. (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

Glossary

- proper length

; the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points; Earth-bound observers measure proper length when measuring the distance between two points that are stationary relative to the Earth

; the distance between two points measured by an observer who is at rest relative to both of the points; Earth-bound observers measure proper length when measuring the distance between two points that are stationary relative to the Earth

- length contraction

, the shortening of the measured length of an object moving relative to the observer’s frame:

, the shortening of the measured length of an object moving relative to the observer’s frame:

Solutions

Check Your Understanding

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com $\begin{array}{r @{{}={}}l} \boldsymbol{L} & \boldsymbol{L_0 \sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} \\[1em] & \boldsymbol{(2.50 \;\textbf{km}) \sqrt{1 - \frac{(0.750c)^2}{c^2}}} \\[1em] & \boldsymbol{1.65 \;\textbf{km}} \end{array}$](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-da1348a2911d454f3632a26964aed0c3_l3.png)

Problems & Exercises

1: 48.6 m

3: (a) 1.387 km = 1.39 km

(b) 0.433 km

(c) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com $\begin{array}{r @{{}={}} l @{{}={}} l} \boldsymbol{L} & \boldsymbol{\frac{L_0}{\gamma}} & \boldsymbol{\frac{1.387 \times 10^3 \;\textbf{m}}{3.20}} \\[1em] & \boldsymbol{433.4 \;\textbf{m}} & \boldsymbol{0.433 \;\textbf{km}} \end{array}$](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-14e0ff0c7f207ef26cb51dfc64b11315_l3.png)

Thus, the distances in parts (a) and (b) are related when ![]() .

.

5: (a) 4.303 y (to four digits to show any effect)

(b) 0.1434 y

(c) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Thus, the two times are related when ![]() .

.

7: (a) 0.250

(b) ![]() must be ≥1

must be ≥1

(c) The Earth-bound observer must measure a shorter length, so it is unreasonable to assume a longer length.