Chapter 20 Electric Current, Resistance, and Ohm’s Law

20.4 Electric Power and Energy

Summary

- Calculate the power dissipated by a resistor and power supplied by a power supply.

- Calculate the cost of electricity under various circumstances.

Power in Electric Circuits

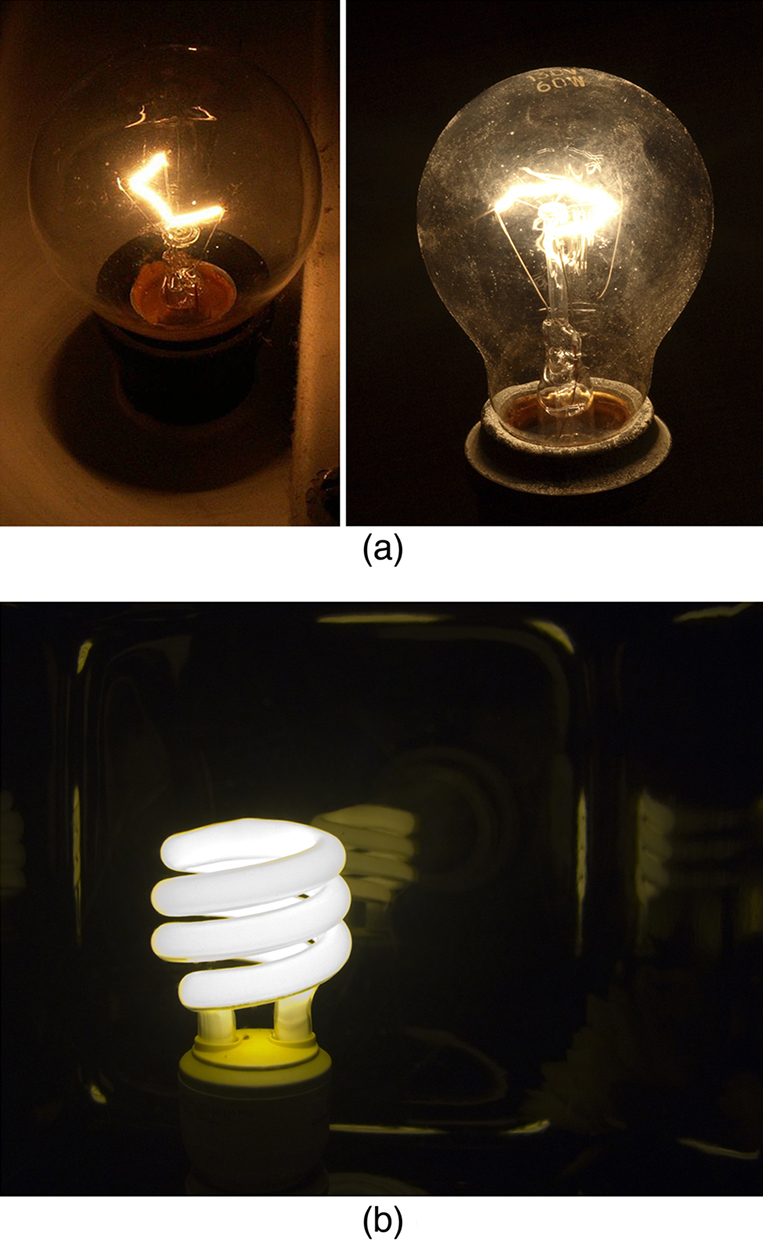

Power is associated by many people with electricity. Knowing that power is the rate of energy use or energy conversion, what is the expression for electric power? Power transmission lines might come to mind. We also think of lightbulbs in terms of their power ratings in watts. Let us compare a 25-W bulb with a 60-W bulb. (See Figure 1(a).) Since both operate on the same voltage, the 60-W bulb must draw more current to have a greater power rating. Thus the 60-W bulb’s resistance must be lower than that of a 25-W bulb. If we increase voltage, we also increase power. For example, when a 25-W bulb that is designed to operate on 120 V is connected to 240 V, it briefly glows very brightly and then burns out. Precisely how are voltage, current, and resistance related to electric power?

Electric energy depends on both the voltage involved and the charge moved. This is expressed most simply as ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the charge moved and

is the charge moved and ![]() is the voltage (or more precisely, the potential difference the charge moves through). Power is the rate at which energy is moved, and so electric power is

is the voltage (or more precisely, the potential difference the charge moves through). Power is the rate at which energy is moved, and so electric power is

Recognizing that current is ![]() (note that

(note that ![]() here), the expression for power becomes

here), the expression for power becomes

Electric power (![]() ) is simply the product of current times voltage. Power has familiar units of watts. Since the SI unit for potential energy (PE) is the joule, power has units of joules per second, or watts. Thus,

) is simply the product of current times voltage. Power has familiar units of watts. Since the SI unit for potential energy (PE) is the joule, power has units of joules per second, or watts. Thus, ![]() . For example, cars often have one or more auxiliary power outlets with which you can charge a cell phone or other electronic devices. These outlets may be rated at 20 A, so that the circuit can deliver a maximum power

. For example, cars often have one or more auxiliary power outlets with which you can charge a cell phone or other electronic devices. These outlets may be rated at 20 A, so that the circuit can deliver a maximum power ![]() . In some applications, electric power may be expressed as volt-amperes or even kilovolt-amperes (

. In some applications, electric power may be expressed as volt-amperes or even kilovolt-amperes (

![]() ).

).

To see the relationship of power to resistance, we combine Ohm’s law with ![]() . Substituting

. Substituting ![]() gives

gives ![]() . Similarly, substituting

. Similarly, substituting ![]() gives

gives ![]() . Three expressions for electric power are listed together here for convenience:

. Three expressions for electric power are listed together here for convenience:

Note that the first equation is always valid, whereas the other two can be used only for resistors. In a simple circuit, with one voltage source and a single resistor, the power supplied by the voltage source and that dissipated by the resistor are identical. (In more complicated circuits, ![]() can be the power dissipated by a single device and not the total power in the circuit.)

can be the power dissipated by a single device and not the total power in the circuit.)

Different insights can be gained from the three different expressions for electric power. For example, ![]() implies that the lower the resistance connected to a given voltage source, the greater the power delivered. Furthermore, since voltage is squared in

implies that the lower the resistance connected to a given voltage source, the greater the power delivered. Furthermore, since voltage is squared in ![]() , the effect of applying a higher voltage is perhaps greater than expected. Thus, when the voltage is doubled to a 25-W bulb, its power nearly quadruples to about 100 W, burning it out. If the bulb’s resistance remained constant, its power would be exactly 100 W, but at the higher temperature its resistance is higher, too.

, the effect of applying a higher voltage is perhaps greater than expected. Thus, when the voltage is doubled to a 25-W bulb, its power nearly quadruples to about 100 W, burning it out. If the bulb’s resistance remained constant, its power would be exactly 100 W, but at the higher temperature its resistance is higher, too.

Example 1: Calculating Power Dissipation and Current: Hot and Cold Power

(a) Consider the examples given in Chapter 20.2 Ohm’s Law: Resistance and Simple Circuits and Chapter 20.3 Resistance and Resistivity. Then find the power dissipated by the car headlight in these examples, both when it is hot and when it is cold. (b) What current does it draw when cold?

Strategy for (a)

For the hot headlight, we know voltage and current, so we can use ![]() to find the power. For the cold headlight, we know the voltage and resistance, so we can use

to find the power. For the cold headlight, we know the voltage and resistance, so we can use ![]() to find the power.

to find the power.

Solution for (a)

Entering the known values of current and voltage for the hot headlight, we obtain

The cold resistance was ![]() , and so the power it uses when first switched on is

, and so the power it uses when first switched on is

Discussion for (a)

The 30 W dissipated by the hot headlight is typical. But the 411 W when cold is surprisingly higher. The initial power quickly decreases as the bulb’s temperature increases and its resistance increases.

Strategy and Solution for (b)

The current when the bulb is cold can be found several different ways. We rearrange one of the power equations, ![]() , and enter known values, obtaining

, and enter known values, obtaining

Discussion for (b)

The cold current is remarkably higher than the steady-state value of 2.50 A, but the current will quickly decline to that value as the bulb’s temperature increases. Most fuses and circuit breakers (used to limit the current in a circuit) are designed to tolerate very high currents briefly as a device comes on. In some cases, such as with electric motors, the current remains high for several seconds, necessitating special “slow blow” fuses.

The Cost of Electricity

The more electric appliances you use and the longer they are left on, the higher your electric bill. This familiar fact is based on the relationship between energy and power. You pay for the energy used. Since ![]() , we see that

, we see that

is the energy used by a device using power ![]() for a time interval

for a time interval ![]() . For example, the more lightbulbs burning, the greater

. For example, the more lightbulbs burning, the greater ![]() used; the longer they are on, the greater

used; the longer they are on, the greater ![]() is. The energy unit on electric bills is the kilowatt-hour (

is. The energy unit on electric bills is the kilowatt-hour (![]() ), consistent with the relationship

), consistent with the relationship ![]() . It is easy to estimate the cost of operating electric appliances if you have some idea of their power consumption rate in watts or kilowatts, the time they are on in hours, and the cost per kilowatt-hour for your electric utility. Kilowatt-hours, like all other specialized energy units such as food calories, can be converted to joules. You can prove to yourself that

. It is easy to estimate the cost of operating electric appliances if you have some idea of their power consumption rate in watts or kilowatts, the time they are on in hours, and the cost per kilowatt-hour for your electric utility. Kilowatt-hours, like all other specialized energy units such as food calories, can be converted to joules. You can prove to yourself that ![]() .

.

The electrical energy (![]() ) used can be reduced either by reducing the time of use or by reducing the power consumption of that appliance or fixture. This will not only reduce the cost, but it will also result in a reduced impact on the environment. Improvements to lighting are some of the fastest ways to reduce the electrical energy used in a home or business. About 20% of a home’s use of energy goes to lighting, while the number for commercial establishments is closer to 40%. Fluorescent lights are about four times more efficient than incandescent lights—this is true for both the long tubes and the compact fluorescent lights (CFL). (See Figure 1(b).) Thus, a 60-W incandescent bulb can be replaced by a 15-W CFL, which has the same brightness and color. CFLs have a bent tube inside a globe or a spiral-shaped tube, all connected to a standard screw-in base that fits standard incandescent light sockets. (Original problems with color, flicker, shape, and high initial investment for CFLs have been addressed in recent years.) The heat transfer from these CFLs is less, and they last up to 10 times longer. The significance of an investment in such bulbs is addressed in the next example. New white LED lights (which are clusters of small LED bulbs) are even more efficient (twice that of CFLs) and last 5 times longer than CFLs. However, their cost is still high.

) used can be reduced either by reducing the time of use or by reducing the power consumption of that appliance or fixture. This will not only reduce the cost, but it will also result in a reduced impact on the environment. Improvements to lighting are some of the fastest ways to reduce the electrical energy used in a home or business. About 20% of a home’s use of energy goes to lighting, while the number for commercial establishments is closer to 40%. Fluorescent lights are about four times more efficient than incandescent lights—this is true for both the long tubes and the compact fluorescent lights (CFL). (See Figure 1(b).) Thus, a 60-W incandescent bulb can be replaced by a 15-W CFL, which has the same brightness and color. CFLs have a bent tube inside a globe or a spiral-shaped tube, all connected to a standard screw-in base that fits standard incandescent light sockets. (Original problems with color, flicker, shape, and high initial investment for CFLs have been addressed in recent years.) The heat transfer from these CFLs is less, and they last up to 10 times longer. The significance of an investment in such bulbs is addressed in the next example. New white LED lights (which are clusters of small LED bulbs) are even more efficient (twice that of CFLs) and last 5 times longer than CFLs. However, their cost is still high.

Making Connections: Energy, Power, and Time

The relationship ![]() is one that you will find useful in many different contexts. The energy your body uses in exercise is related to the power level and duration of your activity, for example. The amount of heating by a power source is related to the power level and time it is applied. Even the radiation dose of an X-ray image is related to the power and time of exposure.

is one that you will find useful in many different contexts. The energy your body uses in exercise is related to the power level and duration of your activity, for example. The amount of heating by a power source is related to the power level and time it is applied. Even the radiation dose of an X-ray image is related to the power and time of exposure.

Example 2: Calculating the Cost Effectiveness of Compact Fluorescent Lights (CFL)

If the cost of electricity in your area is 12 cents per kWh, what is the total cost (capital plus operation) of using a 60-W incandescent bulb for 1000 hours (the lifetime of that bulb) if the bulb cost 25 cents? (b) If we replace this bulb with a compact fluorescent light that provides the same light output, but at one-quarter the wattage, and which costs $1.50 but lasts 10 times longer (10,000 hours), what will that total cost be?

Strategy

To find the operating cost, we first find the energy used in kilowatt-hours and then multiply by the cost per kilowatt-hour.

Solution for (a)

The energy used in kilowatt-hours is found by entering the power and time into the expression for energy:

In kilowatt-hours, this is

Now the electricity cost is

The total cost will be $7.20 for 1000 hours (about one-half year at 5 hours per day).

Solution for (b)

Since the CFL uses only 15 W and not 60 W, the electricity cost will be $7.20/4 = $1.80. The CFL will last 10 times longer than the incandescent, so that the investment cost will be 1/10 of the bulb cost for that time period of use, or 0.1($1.50) = $0.15. Therefore, the total cost will be $1.95 for 1000 hours.

Discussion

Therefore, it is much cheaper to use the CFLs, even though the initial investment is higher. The increased cost of labor that a business must include for replacing the incandescent bulbs more often has not been figured in here.

Making Connections: Take-Home Experiment—Electrical Energy Use Inventory

1) Make a list of the power ratings on a range of appliances in your home or room. Explain why something like a toaster has a higher rating than a digital clock. Estimate the energy consumed by these appliances in an average day (by estimating their time of use). Some appliances might only state the operating current. If the household voltage is 120 V, then use ![]() . 2) Check out the total wattage used in the rest rooms of your school’s floor or building. (You might need to assume the long fluorescent lights in use are rated at 32 W.) Suppose that the building was closed all weekend and that these lights were left on from 6 p.m. Friday until 8 a.m. Monday. What would this oversight cost? How about for an entire year of weekends?

. 2) Check out the total wattage used in the rest rooms of your school’s floor or building. (You might need to assume the long fluorescent lights in use are rated at 32 W.) Suppose that the building was closed all weekend and that these lights were left on from 6 p.m. Friday until 8 a.m. Monday. What would this oversight cost? How about for an entire year of weekends?

Section Summary

- Electric power

is the rate (in watts) that energy is supplied by a source or dissipated by a device.

is the rate (in watts) that energy is supplied by a source or dissipated by a device. - Three expressions for electrical power are

,

,and

- The energy used by a device with a power

over a time

over a time  is

is  .

.

Conceptual Questions

1: Why do incandescent lightbulbs grow dim late in their lives, particularly just before their filaments break?

2: The power dissipated in a resistor is given by ![]() , which means power decreases if resistance increases. Yet this power is also given by

, which means power decreases if resistance increases. Yet this power is also given by ![]() , which means power increases if resistance increases. Explain why there is no contradiction here.

, which means power increases if resistance increases. Explain why there is no contradiction here.

Probles & Exercises

1: What is the power of a ![]() lightning bolt having a current of

lightning bolt having a current of ![]() ?

?

2: What power is supplied to the starter motor of a large truck that draws 250 A of current from a 24.0-V battery hookup?

3: A charge of 4.00 C of charge passes through a pocket calculator’s solar cells in 4.00 h. What is the power output, given the calculator’s voltage output is 3.00 V? (See Figure 2.)

4: How many watts does a flashlight that has ![]() pass through it in 0.500 h use if its voltage is 3.00 V?

pass through it in 0.500 h use if its voltage is 3.00 V?

5: Find the power dissipated in each of these extension cords: (a) an extension cord having a ![]() resistance and through which 5.00 A is flowing; (b) a cheaper cord utilizing thinner wire and with a resistance of

resistance and through which 5.00 A is flowing; (b) a cheaper cord utilizing thinner wire and with a resistance of ![]()

6: Verify that the units of a volt-ampere are watts, as implied by the equation ![]() .

.

7: Show that the units ![]() , as implied by the equation

, as implied by the equation ![]() .

.

8: Show that the units ![]() , as implied by the equation

, as implied by the equation ![]() .

.

9: Verify the energy unit equivalence that ![]() .

.

10: Electrons in an X-ray tube are accelerated through ![]() and directed toward a target to produce X-rays. Calculate the power of the electron beam in this tube if it has a current of 15.0 mA.

and directed toward a target to produce X-rays. Calculate the power of the electron beam in this tube if it has a current of 15.0 mA.

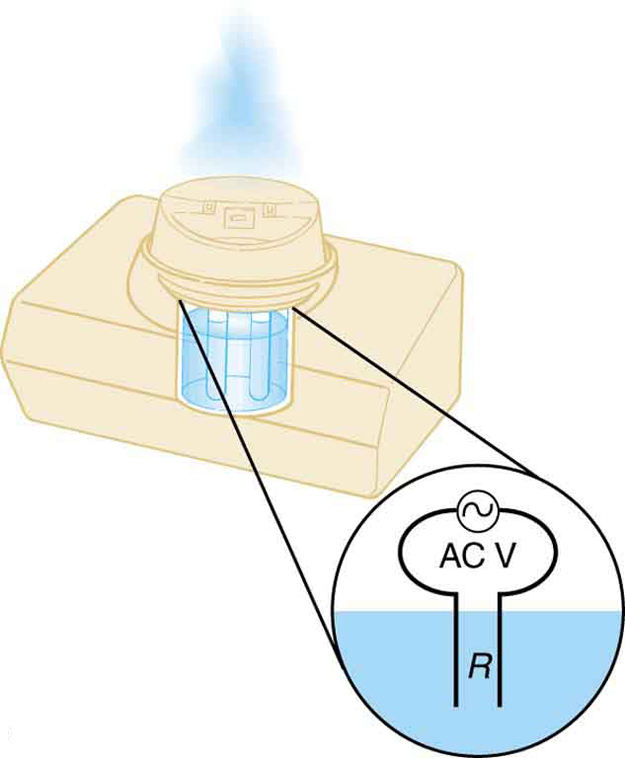

11: An electric water heater consumes 5.00 kW for 2.00 h per day. What is the cost of running it for one year if electricity costs ![]() ? See Figure 3.

? See Figure 3.

12: With a 1200-W toaster, how much electrical energy is needed to make a slice of toast (cooking time = 1 minute)? At ![]() , how much does this cost?

, how much does this cost?

13: What would be the maximum cost of a CFL such that the total cost (investment plus operating) would be the same for both CFL and incandescent 60-W bulbs? Assume the cost of the incandescent bulb is 25 cents and that electricity costs ![]() . Calculate the cost for 1000 hours, as in the cost effectiveness of CFL example.

. Calculate the cost for 1000 hours, as in the cost effectiveness of CFL example.

14: Some makes of older cars have 6.00-V electrical systems. (a) What is the hot resistance of a 30.0-W headlight in such a car? (b) What current flows through it?

15: Alkaline batteries have the advantage of putting out constant voltage until very nearly the end of their life. How long will an alkaline battery rated at ![]() and 1.58 V keep a 1.00-W flashlight bulb burning?

and 1.58 V keep a 1.00-W flashlight bulb burning?

16: A cauterizer, used to stop bleeding in surgery, puts out 2.00 mA at 15.0 kV. (a) What is its power output? (b) What is the resistance of the path?

17: The average television is said to be on 6 hours per day. Estimate the yearly cost of electricity to operate 100 million TVs, assuming their power consumption averages 150 W and the cost of electricity averages ![]() .

.

18: An old lightbulb draws only 50.0 W, rather than its original 60.0 W, due to evaporative thinning of its filament. By what factor is its diameter reduced, assuming uniform thinning along its length? Neglect any effects caused by temperature differences.

19: 00-gauge copper wire has a diameter of 9.266 mm. Calculate the power loss in a kilometer of such wire when it carries ![]() .

.

20: Integrated Concepts

Cold vaporizers pass a current through water, evaporating it with only a small increase in temperature. One such home device is rated at 3.50 A and utilizes 120 V AC with 95.0% efficiency. (a) What is the vaporization rate in grams per minute? (b) How much water must you put into the vaporizer for 8.00 h of overnight operation? (See Figure 4.)

21: Integrated Concepts

(a) What energy is dissipated by a lightning bolt having a 20,000-A current, a voltage of ![]() , and a length of 1.00 ms? (b) What mass of tree sap could be raised from 18.0ºC to its boiling point and then evaporated by this energy, assuming sap has the same thermal characteristics as water?

, and a length of 1.00 ms? (b) What mass of tree sap could be raised from 18.0ºC to its boiling point and then evaporated by this energy, assuming sap has the same thermal characteristics as water?

22: Integrated Concepts

What current must be produced by a 12.0-V battery-operated bottle warmer in order to heat 75.0 g of glass, 250 g of baby formula, and ![]() of aluminum from 20.0ºC to 90.0ºC in 5.00 min?

of aluminum from 20.0ºC to 90.0ºC in 5.00 min?

23: Integrated Concepts

How much time is needed for a surgical cauterizer to raise the temperature of 1.00 g of tissue from 37.0ºC to 100ºC and then boil away 0.500 g of water, if it puts out 2.00 mA at 15.0 kV? Ignore heat transfer to the surroundings.

24: Integrated Concepts

24: Hydroelectric generators (see Figure 5) at Hoover Dam produce a maximum current of ![]() at 250 kV. (a) What is the power output? (b) The water that powers the generators enters and leaves the system at low speed (thus its kinetic energy does not change) but loses 160 m in altitude. How many cubic meters per second are needed, assuming 85.0% efficiency?

at 250 kV. (a) What is the power output? (b) The water that powers the generators enters and leaves the system at low speed (thus its kinetic energy does not change) but loses 160 m in altitude. How many cubic meters per second are needed, assuming 85.0% efficiency?

25: Integrated Concepts

(a) Assuming 95.0% efficiency for the conversion of electrical power by the motor, what current must the 12.0-V batteries of a 750-kg electric car be able to supply: (a) To accelerate from rest to 25.0 m/s in 1.00 min? (b) To climb a

![]() -high hill in 2.00 min at a constant 25.0-m/s speed while exerting

-high hill in 2.00 min at a constant 25.0-m/s speed while exerting

![]() of force to overcome air resistance and friction? (c) To travel at a constant 25.0-m/s speed, exerting a

of force to overcome air resistance and friction? (c) To travel at a constant 25.0-m/s speed, exerting a ![]() force to overcome air resistance and friction? See Figure 6.

force to overcome air resistance and friction? See Figure 6.

26: Integrated Concepts

A light-rail commuter train draws 630 A of 650-V DC electricity when accelerating. (a) What is its power consumption rate in kilowatts? (b) How long does it take to reach 20.0 m/s starting from rest if its loaded mass is ![]() , assuming 95.0% efficiency and constant power? (c) Find its average acceleration. (d) Discuss how the acceleration you found for the light-rail train compares to what might be typical for an automobile.

, assuming 95.0% efficiency and constant power? (c) Find its average acceleration. (d) Discuss how the acceleration you found for the light-rail train compares to what might be typical for an automobile.

27: Integrated Concepts

(a) An aluminum power transmission line has a resistance of ![]() . What is its mass per kilometer? (b) What is the mass per kilometer of a copper line having the same resistance? A lower resistance would shorten the heating time. Discuss the practical limits to speeding the heating by lowering the resistance.

. What is its mass per kilometer? (b) What is the mass per kilometer of a copper line having the same resistance? A lower resistance would shorten the heating time. Discuss the practical limits to speeding the heating by lowering the resistance.

28: Integrated Concepts

(a) An immersion heater utilizing 120 V can raise the temperature of a ![]() aluminum cup containing 350 g of water from 20.0ºC to 95.0ºC in 2.00 min. Find its resistance, assuming it is constant during the process. (b) A lower resistance would shorten the heating time. Discuss the practical limits to speeding the heating by lowering the resistance.

aluminum cup containing 350 g of water from 20.0ºC to 95.0ºC in 2.00 min. Find its resistance, assuming it is constant during the process. (b) A lower resistance would shorten the heating time. Discuss the practical limits to speeding the heating by lowering the resistance.

29: Integrated Concepts

(a) What is the cost of heating a hot tub containing 1500 kg of water from 10.0ºC to 40.0ºC, assuming 75.0% efficiency to account for heat transfer to the surroundings? The cost of electricity is ![]() . (b) What current was used by the 220-V AC electric heater, if this took 4.00 h?

. (b) What current was used by the 220-V AC electric heater, if this took 4.00 h?

30: Unreasonable Results

(a) What current is needed to transmit ![]() of power at 480 V? (b) What power is dissipated by the transmission lines if they have a

of power at 480 V? (b) What power is dissipated by the transmission lines if they have a ![]() resistance? (c) What is unreasonable about this result? (d) Which assumptions are unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

resistance? (c) What is unreasonable about this result? (d) Which assumptions are unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

31: Unreasonable Results

(a) What current is needed to transmit ![]() of power at 10.0 kV? (b) Find the resistance of 1.00 km of wire that would cause a 0.0100% power loss. (c) What is the diameter of a 1.00-km-long copper wire having this resistance? (d) What is unreasonable about these results? (e) Which assumptions are unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

of power at 10.0 kV? (b) Find the resistance of 1.00 km of wire that would cause a 0.0100% power loss. (c) What is the diameter of a 1.00-km-long copper wire having this resistance? (d) What is unreasonable about these results? (e) Which assumptions are unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

32: Construct Your Own Problem

Consider an electric immersion heater used to heat a cup of water to make tea. Construct a problem in which you calculate the needed resistance of the heater so that it increases the temperature of the water and cup in a reasonable amount of time. Also calculate the cost of the electrical energy used in your process. Among the things to be considered are the voltage used, the masses and heat capacities involved, heat losses, and the time over which the heating takes place. Your instructor may wish for you to consider a thermal safety switch (perhaps bimetallic) that will halt the process before damaging temperatures are reached in the immersion unit.

Glossary

- electric power

- the rate at which electrical energy is supplied by a source or dissipated by a device; it is the product of current times voltage

Solutions

Problems & Exercise

1: ![]()

5: (a) 1.50 W

(b) 7.50 W

7: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

9: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

11: $438/y

13: $6.25

15: 1.58 h

17: $3.94 billion/year

19: 25.5 W

21: (a) ![]()

(b) 769 kg

23: 45.0 s

25: (a) 343 A

(b) ![]()

(c) ![]()

27: (a) ![]()

(b) ![]()

3o: (a) ![]()

(b) ![]()

(c) The transmission lines dissipate more power than they are supposed to transmit.

(d) A voltage of 480 V is unreasonably low for a transmission voltage. Long-distance transmission lines are kept at much higher voltages (often hundreds of kilovolts) to reduce power losses.