Chapter 22 Magnetism

22.7 Magnetic Force on a Current-Carrying Conductor

Summary

- Describe the effects of a magnetic force on a current-carrying conductor.

- Calculate the magnetic force on a current-carrying conductor.

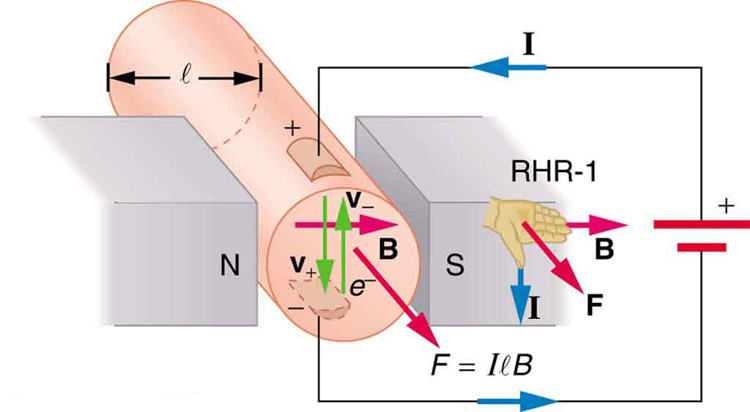

Because charges ordinarily cannot escape a conductor, the magnetic force on charges moving in a conductor is transmitted to the conductor itself.

We can derive an expression for the magnetic force on a current by taking a sum of the magnetic forces on individual charges. (The forces add because they are in the same direction.) The force on an individual charge moving at the drift velocity ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() . Taking

. Taking ![]() to be uniform over a length of wire

to be uniform over a length of wire ![]() and zero elsewhere, the total magnetic force on the wire is then

and zero elsewhere, the total magnetic force on the wire is then ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of charge carriers in the section of wire of length

is the number of charge carriers in the section of wire of length ![]() . Now,

. Now, ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of charge carriers per unit volume and

is the number of charge carriers per unit volume and ![]() is the volume of wire in the field. Noting that

is the volume of wire in the field. Noting that ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the cross-sectional area of the wire, then the force on the wire is

is the cross-sectional area of the wire, then the force on the wire is ![]() . Gathering terms,

. Gathering terms,

Because ![]() (see Chapter 20.1 Current),

(see Chapter 20.1 Current),

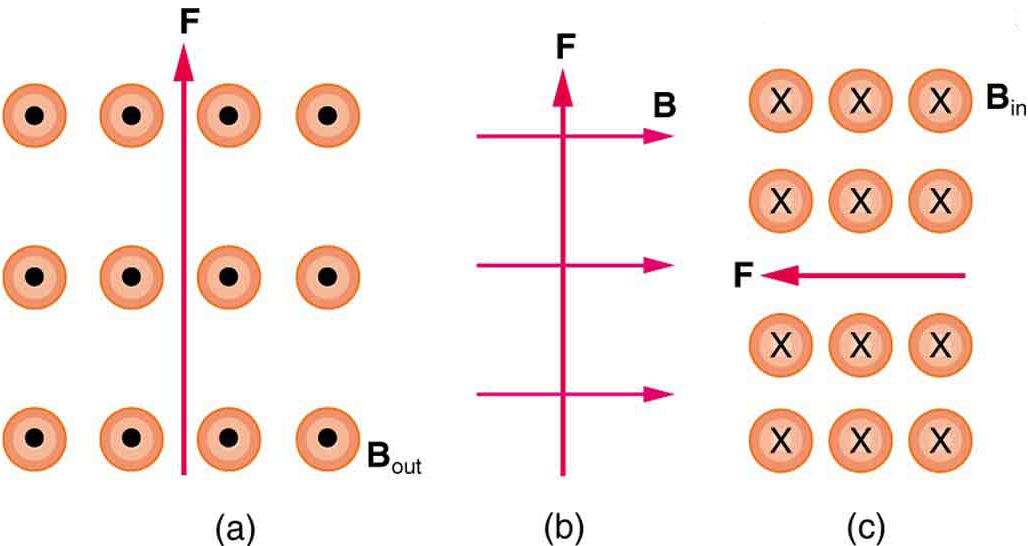

is the equation for magnetic force on a length ![]() of wire carrying a current

of wire carrying a current ![]() in a uniform magnetic field

in a uniform magnetic field ![]() , as shown in Figure 2. If we divide both sides of this expression by

, as shown in Figure 2. If we divide both sides of this expression by ![]() , we find that the magnetic force per unit length of wire in a uniform field is

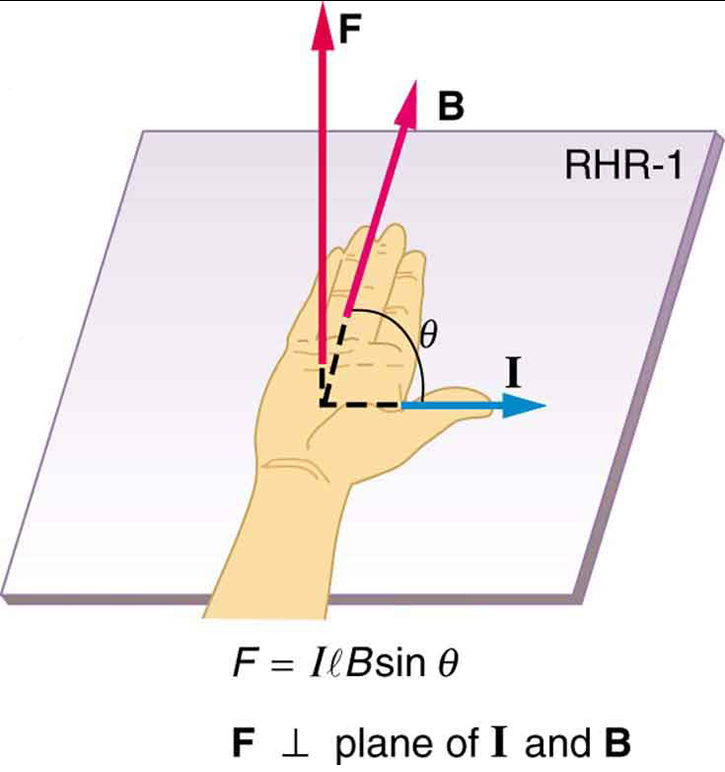

, we find that the magnetic force per unit length of wire in a uniform field is ![]() . The direction of this force is given by RHR-1, with the thumb in the direction of the current

. The direction of this force is given by RHR-1, with the thumb in the direction of the current ![]() . Then, with the fingers in the direction of

. Then, with the fingers in the direction of ![]() , a perpendicular to the palm points in the direction of

, a perpendicular to the palm points in the direction of ![]() , as in Figure 2.

, as in Figure 2.

Calculating Magnetic Force on a Current-Carrying Wire: A Strong Magnetic Field

Calculate the force on the wire shown in Figure 1, given ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Strategy

The force can be found with the given information by using ![]() and noting that the angle

and noting that the angle ![]() between

between ![]() and

and ![]() is

is ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() .

.

Solution

Entering the given values into ![]() yields

yields

The units for tesla are ![]() ; thus,

; thus,

Discussion

This large magnetic field creates a significant force on a small length of wire.

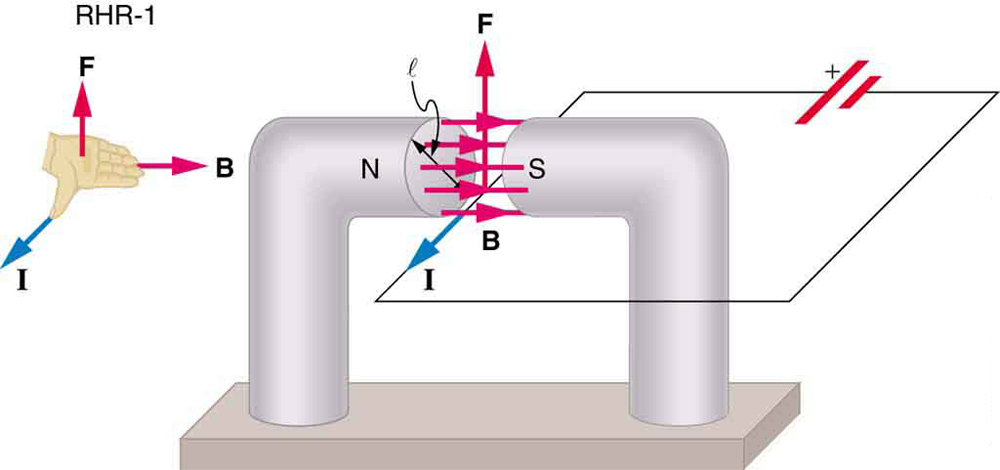

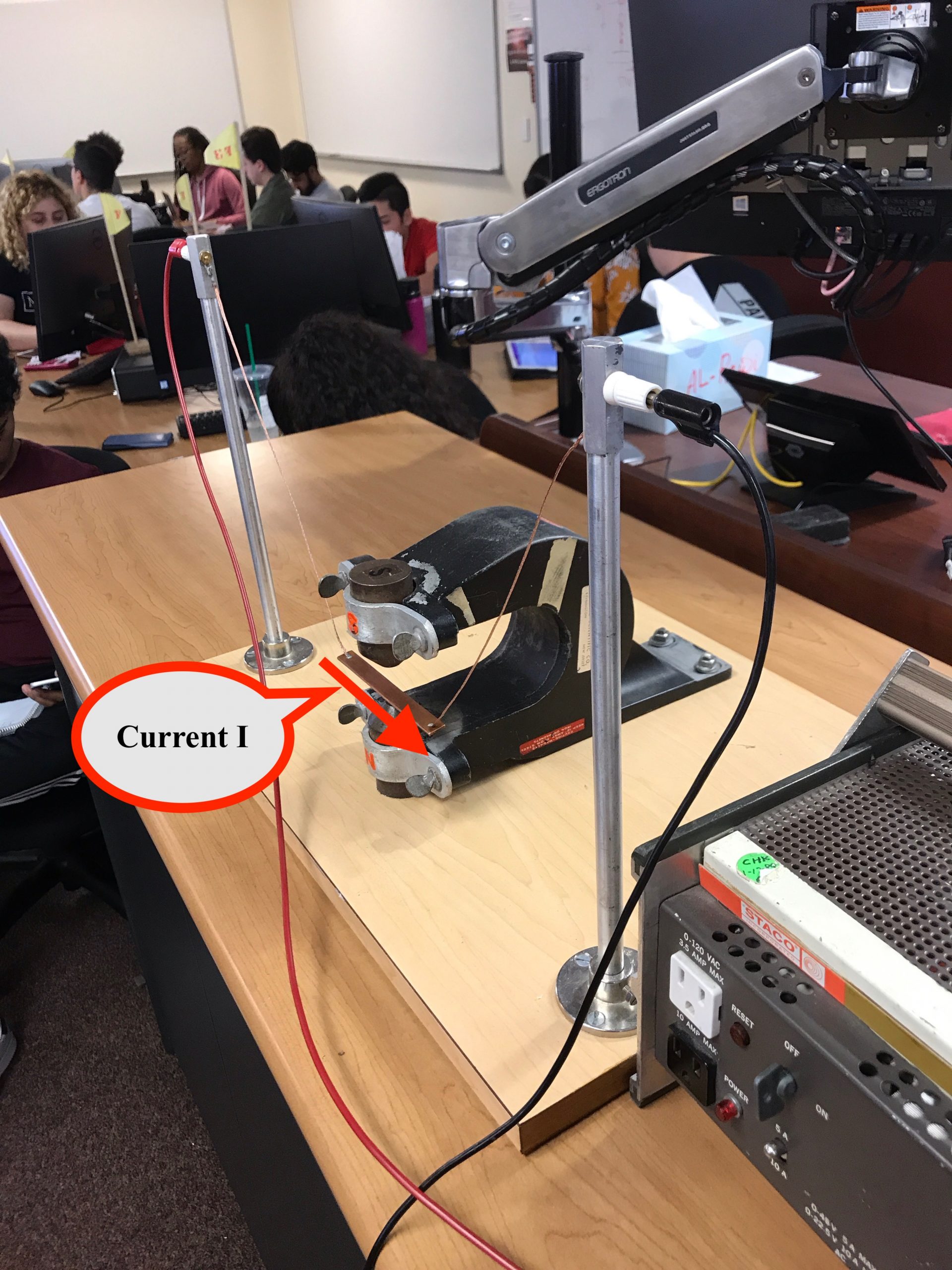

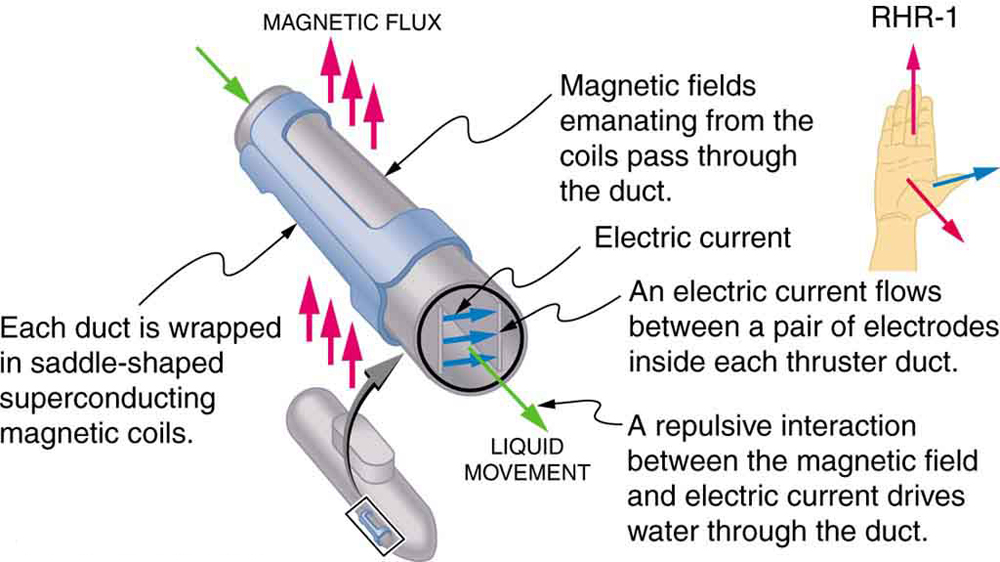

Magnetic force on current-carrying conductors is used to convert electric energy to work. (Motors are a prime example—they employ loops of wire and are considered in the next section.) Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) is the technical name given to a clever application where magnetic force pumps fluids without moving mechanical parts. (See Figure 3.)

A strong magnetic field is applied across a tube and a current is passed through the fluid at right angles to the field, resulting in a force on the fluid parallel to the tube axis as shown. The absence of moving parts makes this attractive for moving a hot, chemically active substance, such as the liquid sodium employed in some nuclear reactors. Experimental artificial hearts are testing with this technique for pumping blood, perhaps circumventing the adverse effects of mechanical pumps. (Cell membranes, however, are affected by the large fields needed in MHD, delaying its practical application in humans.) MHD propulsion for nuclear submarines has been proposed, because it could be considerably quieter than conventional propeller drives. The deterrent value of nuclear submarines is based on their ability to hide and survive a first or second nuclear strike. As we slowly disassemble our nuclear weapons arsenals, the submarine branch will be the last to be decommissioned because of this ability (See Figure 4.) Existing MHD drives are heavy and inefficient—much development work is needed.

Section Summary

- The magnetic force on current-carrying conductors is given by

where

is the current,

is the current,  is the length of a straight conductor in a uniform magnetic field

is the length of a straight conductor in a uniform magnetic field  , and

, and  is the angle between

is the angle between  and

and  . The force follows RHR-1 with the thumb in the direction of

. The force follows RHR-1 with the thumb in the direction of  .

.

Conceptual Questions

1: Draw a sketch of the situation in Figure 1 showing the direction of electrons carrying the current, and use RHR-1 to verify the direction of the force on the wire.

2: Verify that the direction of the force in an MHD drive, such as that in Figure 3, does not depend on the sign of the charges carrying the current across the fluid.

3: Why would a magnetohydrodynamic drive work better in ocean water than in fresh water? Also, why would superconducting magnets be desirable?

4: Which is more likely to interfere with compass readings, AC current in your refrigerator or DC current when you start your car? Explain.

Problems & Exercises

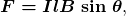

1: What is the direction of the magnetic force on the current in each of the six cases in Figure 5?

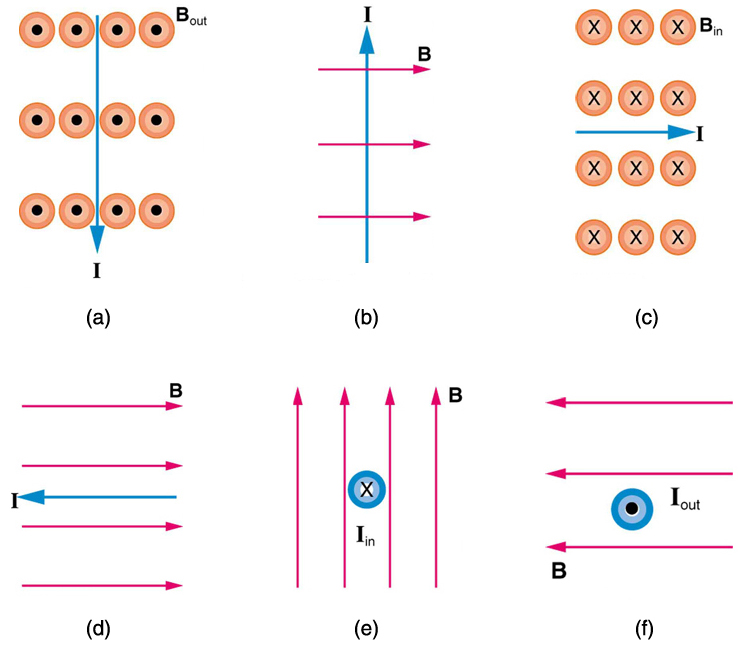

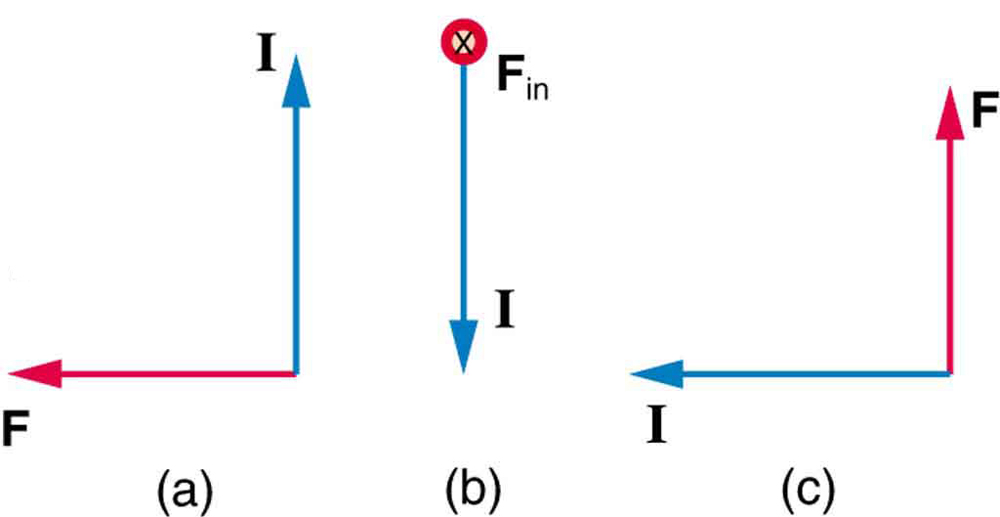

2: What is the direction of a current that experiences the magnetic force shown in each of the three cases in Figure 6, assuming the current runs perpendicular to ![]() ?

?

3: What is the direction of the magnetic field that produces the magnetic force shown on the currents in each of the three cases in Figure 7, assuming ![]() is perpendicular to

is perpendicular to ![]() ?

?

4: (a) What is the force per meter on a lightning bolt at the equator that carries 20,000 A perpendicular to the Earth’s ![]() field? (b) What is the direction of the force if the current is straight up and the Earth’s field direction is due north, parallel to the ground?

field? (b) What is the direction of the force if the current is straight up and the Earth’s field direction is due north, parallel to the ground?

5: (a) A DC power line for a light-rail system carries 1000 A at an angle of ![]() to the Earth’s

to the Earth’s ![]() field. What is the force on a 100-m section of this line? (b) Discuss practical concerns this presents, if any.

field. What is the force on a 100-m section of this line? (b) Discuss practical concerns this presents, if any.

6: What force is exerted on the water in an MHD drive utilizing a 25.0-cm-diameter tube, if 100-A current is passed across the tube that is perpendicular to a 2.00-T magnetic field? (The relatively small size of this force indicates the need for very large currents and magnetic fields to make practical MHD drives.)

7: A wire carrying a 30.0-A current passes between the poles of a strong magnet that is perpendicular to its field and experiences a 2.16-N force on the 4.00 cm of wire in the field. What is the average field strength?

8: (a) A 0.750-m-long section of cable carrying current to a car starter motor makes an angle of ![]() with the Earth’s

with the Earth’s ![]() field. What is the current when the wire experiences a force of

field. What is the current when the wire experiences a force of ![]() ? (b) If you run the wire between the poles of a strong horseshoe magnet, subjecting 5.00 cm of it to a 1.75-T field, what force is exerted on this segment of wire?

? (b) If you run the wire between the poles of a strong horseshoe magnet, subjecting 5.00 cm of it to a 1.75-T field, what force is exerted on this segment of wire?

9: (a) What is the angle between a wire carrying an 8.00-A current and the 1.20-T field it is in if 50.0 cm of the wire experiences a magnetic force of 2.40 N? (b) What is the force on the wire if it is rotated to make an angle of ![]() with the field?

with the field?

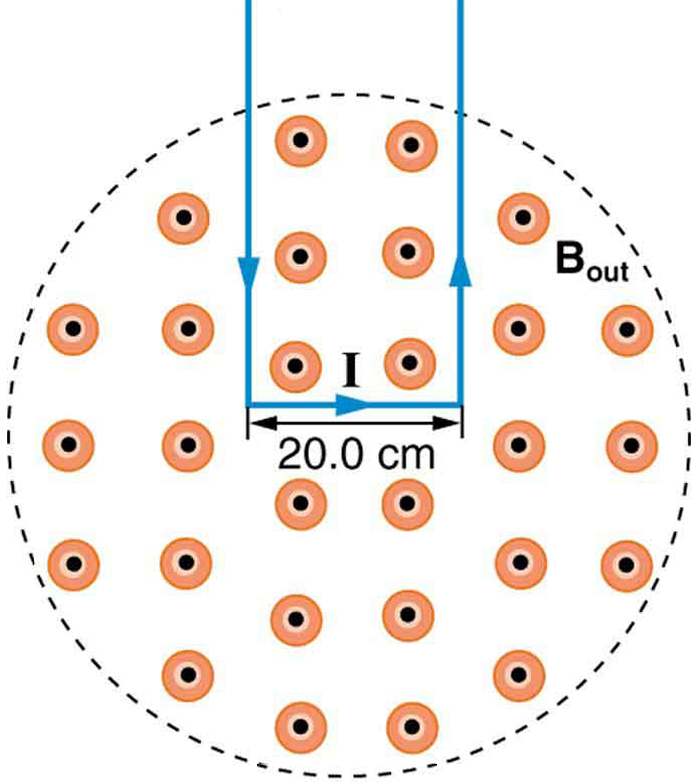

10: The force on the rectangular loop of wire in the magnetic field in Figure 8 can be used to measure field strength. The field is uniform, and the plane of the loop is perpendicular to the field. (a) What is the direction of the magnetic force on the loop? Justify the claim that the forces on the sides of the loop are equal and opposite, independent of how much of the loop is in the field and do not affect the net force on the loop. (b) If a current of 5.00 A is used, what is the force per tesla on the 20.0-cm-wide loop?

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: (a) west (left)

(b) into page

(c) north (up)

(d) no force

(e) east (right)

(f) south (down)

3: (a) into page

(b) west (left)

(c) out of page

5: (a) 2.50 N

(b) This is about half a pound of force per 100 m of wire, which is much less than the weight of the wire itself. Therefore, it does not cause any special concerns.

7: 1.80 T

9: (a) ![]()

(b) 4.80 N