Chapter 20 Electric Current, Resistance, and Ohm’s Law

20.5 Alternating Current versus Direct Current

Summary

- Explain the differences and similarities between AC and DC current.

- Calculate rms voltage, current, and average power.

- Explain why AC current is used for power transmission.

Alternating Current

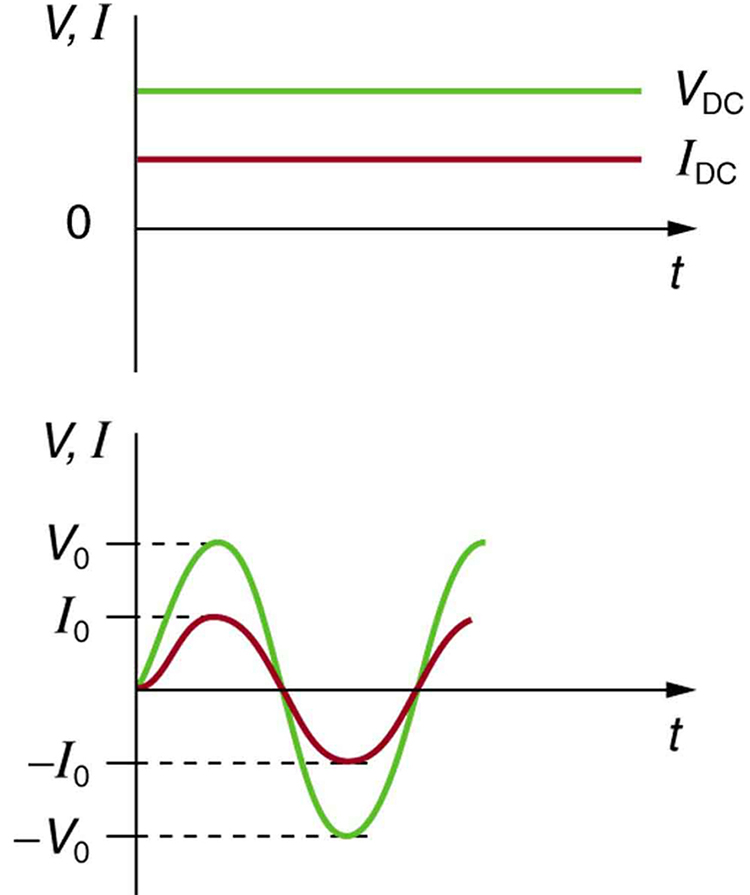

Most of the examples dealt with so far, and particularly those utilizing batteries, have constant voltage sources. Once the current is established, it is thus also a constant. Direct current (DC) is the flow of electric charge in only one direction. It is the steady state of a constant-voltage circuit. Most well-known applications, however, use a time-varying voltage source. Alternating current (AC) is the flow of electric charge that periodically reverses direction. If the source varies periodically, particularly sinusoidally, the circuit is known as an alternating current circuit. Examples include the commercial and residential power that serves so many of our needs. Figure 1 shows graphs of voltage and current versus time for typical DC and AC power. The AC voltages and frequencies commonly used in homes and businesses vary around the world.

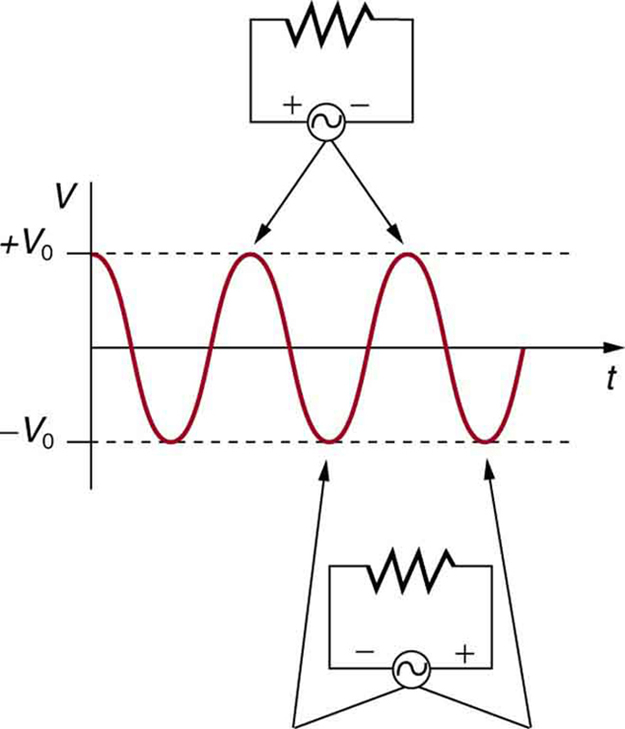

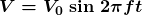

Figure 2 shows a schematic of a simple circuit with an AC voltage source. The voltage between the terminals fluctuates as shown, with the AC voltage given by

where ![]() is the voltage at time

is the voltage at time ![]() ,

, ![]() is the peak voltage, and

is the peak voltage, and ![]() is the frequency in hertz. For this simple resistance circuit,

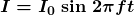

is the frequency in hertz. For this simple resistance circuit, ![]() , and so the AC current is

, and so the AC current is

where ![]() is the current at time

is the current at time ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the peak current. For this example, the voltage and current are said to be in phase, as seen in Figure 1(b).

is the peak current. For this example, the voltage and current are said to be in phase, as seen in Figure 1(b).

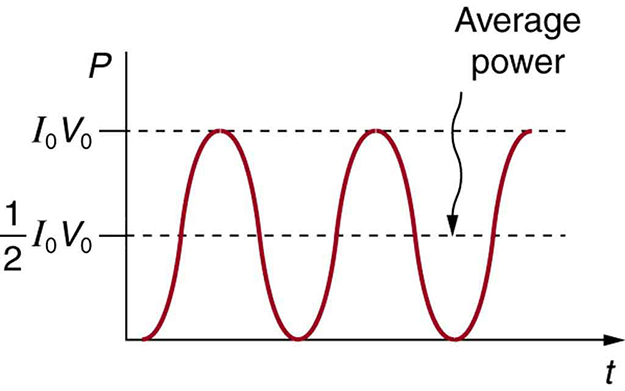

Current in the resistor alternates back and forth just like the driving voltage, since ![]() . If the resistor is a fluorescent light bulb, for example, it brightens and dims 120 times per second as the current repeatedly goes through zero. A 120-Hz flicker is too rapid for your eyes to detect, but if you wave your hand back and forth between your face and a fluorescent light, you will see a stroboscopic effect evidencing AC. The fact that the light output fluctuates means that the power is fluctuating. The power supplied is

. If the resistor is a fluorescent light bulb, for example, it brightens and dims 120 times per second as the current repeatedly goes through zero. A 120-Hz flicker is too rapid for your eyes to detect, but if you wave your hand back and forth between your face and a fluorescent light, you will see a stroboscopic effect evidencing AC. The fact that the light output fluctuates means that the power is fluctuating. The power supplied is ![]() . Using the expressions for

. Using the expressions for ![]() and

and ![]() above, we see that the time dependence of power is

above, we see that the time dependence of power is ![]() , as shown in Figure 3.

, as shown in Figure 3.

Making Connections: Take-Home Experiment—AC/DC Lights

Wave your hand back and forth between your face and a fluorescent light bulb. Do you observe the same thing with the headlights on your car? Explain what you observe. Warning: Do not look directly at very bright light.

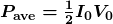

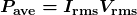

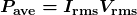

We are most often concerned with average power rather than its fluctuations—that 60-W light bulb in your desk lamp has an average power consumption of 60 W, for example. As illustrated in Figure 3, the average power ![]() is

is

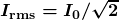

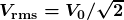

This is evident from the graph, since the areas above and below the ![]() line are equal, but it can also be proven using trigonometric identities. Similarly, we define an average or rms current

line are equal, but it can also be proven using trigonometric identities. Similarly, we define an average or rms current ![]() and average or rms voltage

and average or rms voltage ![]() to be, respectively,

to be, respectively,

and

where rms stands for root mean square, a particular kind of average. In general, to obtain a root mean square, the particular quantity is squared, its mean (or average) is found, and the square root is taken. This is useful for AC, since the average value is zero. Now,

which gives

as stated above. It is standard practice to quote ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() rather than the peak values. For example, most household electricity is 120 V AC, which means that

rather than the peak values. For example, most household electricity is 120 V AC, which means that ![]() is 120 V. The common 10-A circuit breaker will interrupt a sustained

is 120 V. The common 10-A circuit breaker will interrupt a sustained ![]() greater than 10 A. Your 1.0-kW microwave oven consumes

greater than 10 A. Your 1.0-kW microwave oven consumes ![]() , and so on. You can think of these rms and average values as the equivalent DC values for a simple resistive circuit.

, and so on. You can think of these rms and average values as the equivalent DC values for a simple resistive circuit.

To summarize, when dealing with AC, Ohm’s law and the equations for power are completely analogous to those for DC, but rms and average values are used for AC. Thus, for AC, Ohm’s law is written

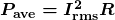

The various expressions for AC power ![]() are

are

and

Example 1: Peak Voltage and Power for AC

(a) What is the value of the peak voltage for 120-V AC power? (b) What is the peak power consumption rate of a 60.0-W AC light bulb?

Strategy

We are told that ![]() is 120 V and

is 120 V and ![]() is 60.0 W. We can use

is 60.0 W. We can use ![]() to find the peak voltage, and we can manipulate the definition of power to find the peak power from the given average power.

to find the peak voltage, and we can manipulate the definition of power to find the peak power from the given average power.

Solution for (a)

Solving the equation ![]() for the peak voltage

for the peak voltage ![]() and substituting the known value for

and substituting the known value for ![]() gives

gives

Discussion for (a)

This means that the AC voltage swings from 170 V to –170 V and back 60 times every second. An equivalent DC voltage is a constant 120 V.

Solution for (b)

Peak power is peak current times peak voltage. Thus,

We know the average power is 60.0 W, and so

Discussion

So the power swings from zero to 120 W one hundred twenty times per second (twice each cycle), and the power averages 60 W.

Why Use AC for Power Distribution?

Most large power-distribution systems are AC. Moreover, the power is transmitted at much higher voltages than the 120-V AC (240 V in most parts of the world) we use in homes and on the job. Economies of scale make it cheaper to build a few very large electric power-generation plants than to build numerous small ones. This necessitates sending power long distances, and it is obviously important that energy losses en route be minimized. High voltages can be transmitted with much smaller power losses than low voltages, as we shall see. (See Figure 4.) For safety reasons, the voltage at the user is reduced to familiar values. The crucial factor is that it is much easier to increase and decrease AC voltages than DC, so AC is used in most large power distribution systems.

Example 2: Power Losses Are Less for High-Voltage Transmission

(a) What current is needed to transmit 100 MW of power at 200 kV? (b) What is the power dissipated by the transmission lines if they have a resistance of ![]() ? (c) What percentage of the power is lost in the transmission lines?

? (c) What percentage of the power is lost in the transmission lines?

Strategy

We are given ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the resistance of the lines is

, and the resistance of the lines is ![]() . Using these givens, we can find the current flowing (from

. Using these givens, we can find the current flowing (from ![]() ) and then the power dissipated in the lines (

) and then the power dissipated in the lines (![]() ), and we take the ratio to the total power transmitted.

), and we take the ratio to the total power transmitted.

Solution

To find the current, we rearrange the relationship ![]() and substitute known values. This gives

and substitute known values. This gives

Solution

Knowing the current and given the resistance of the lines, the power dissipated in them is found from ![]() . Substituting the known values gives

. Substituting the known values gives

Solution

The percent loss is the ratio of this lost power to the total or input power, multiplied by 100:

Discussion

One-fourth of a percent is an acceptable loss. Note that if 100 MW of power had been transmitted at 25 kV, then a current of 4000 A would have been needed. This would result in a power loss in the lines of 16.0 MW, or 16.0% rather than 0.250%. The lower the voltage, the more current is needed, and the greater the power loss in the fixed-resistance transmission lines. Of course, lower-resistance lines can be built, but this requires larger and more expensive wires. If superconducting lines could be economically produced, there would be no loss in the transmission lines at all. But, as we shall see in a later chapter, there is a limit to current in superconductors, too. In short, high voltages are more economical for transmitting power, and AC voltage is much easier to raise and lower, so that AC is used in most large-scale power distribution systems.

It is widely recognized that high voltages pose greater hazards than low voltages. But, in fact, some high voltages, such as those associated with common static electricity, can be harmless. So it is not voltage alone that determines a hazard. It is not so widely recognized that AC shocks are often more harmful than similar DC shocks. Thomas Edison thought that AC shocks were more harmful and set up a DC power-distribution system in New York City in the late 1800s. There were bitter fights, in particular between Edison and George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla, who were advocating the use of AC in early power-distribution systems. AC has prevailed largely due to transformers and lower power losses with high-voltage transmission.

PhET Explorations: Generator

Generate electricity with a bar magnet! Discover the physics behind the phenomena by exploring magnets and how you can use them to make a bulb light.

Section Summary

- Direct current (DC) is the flow of electric current in only one direction. It refers to systems where the source voltage is constant.

- The voltage source of an alternating current (AC) system puts out

, where

, where  is the voltage at time

is the voltage at time  ,

,  is the peak voltage, and

is the peak voltage, and  is the frequency in hertz.

is the frequency in hertz. - In a simple circuit,

and AC current is

and AC current is  , where

, where  is the current at time

is the current at time  , and

, and  is the peak current.

is the peak current. - The average AC power is

.

. - Average (rms) current

and average (rms) voltage

and average (rms) voltage  are

are  and

and  , where rms stands for root mean square.

, where rms stands for root mean square. - Thus,

.

. - Ohm’s law for AC is

.

. - Expressions for the average power of an AC circuit are

,

,  , and

, and  , analogous to the expressions for DC circuits.

, analogous to the expressions for DC circuits.

Conceptual Questions

1: Give an example of a use of AC power other than in the household. Similarly, give an example of a use of DC power other than that supplied by batteries.

2: Why do voltage, current, and power go through zero 120 times per second for 60-Hz AC electricity?

3: You are riding in a train, gazing into the distance through its window. As close objects streak by, you notice that the nearby fluorescent lights make dashed streaks. Explain.

Problem Exercises

1: (a) What is the hot resistance of a 25-W light bulb that runs on 120-V AC? (b) If the bulb’s operating temperature is 2700ºC, what is its resistance at 2600ºC?

2: Certain heavy industrial equipment uses AC power that has a peak voltage of 679 V. What is the rms voltage?

3: A certain circuit breaker trips when the rms current is 15.0 A. What is the corresponding peak current?

4: Military aircraft use 400-Hz AC power, because it is possible to design lighter-weight equipment at this higher frequency. What is the time for one complete cycle of this power?

5: A North American tourist takes his 25.0-W, 120-V AC razor to Europe, finds a special adapter, and plugs it into 240 V AC. Assuming constant resistance, what power does the razor consume as it is ruined?

6: In this problem, you will verify statements made at the end of the power losses for Example 2. (a) What current is needed to transmit 100 MW of power at a voltage of 25.0 kV? (b) Find the power loss in a ![]() transmission line. (c) What percent loss does this represent?

transmission line. (c) What percent loss does this represent?

7: A small office-building air conditioner operates on 408-V AC and consumes 50.0 kW. (a) What is its effective resistance? (b) What is the cost of running the air conditioner during a hot summer month when it is on 8.00 h per day for 30 days and electricity costs ![]() ?

?

8: What is the peak power consumption of a 120-V AC microwave oven that draws 10.0 A?

9: What is the peak current through a 500-W room heater that operates on 120-V AC power?

10: Two different electrical devices have the same power consumption, but one is meant to be operated on 120-V AC and the other on 240-V AC. (a) What is the ratio of their resistances? (b) What is the ratio of their currents? (c) Assuming its resistance is unaffected, by what factor will the power increase if a 120-V AC device is connected to 240-V AC?

11: Nichrome wire is used in some radiative heaters. (a) Find the resistance needed if the average power output is to be 1.00 kW utilizing 120-V AC. (b) What length of Nichrome wire, having a cross-sectional area of ![]() , is needed if the operating temperature is 500º C? (c) What power will it draw when first switched on?

, is needed if the operating temperature is 500º C? (c) What power will it draw when first switched on?

12: Find the time after ![]() when the instantaneous voltage of 60-Hz AC first reaches the following values: (a)

when the instantaneous voltage of 60-Hz AC first reaches the following values: (a) ![]() (b)

(b) ![]() (c) 0.

(c) 0.

13: (a) At what two times in the first period following ![]() does the instantaneous voltage in 60-Hz AC equal

does the instantaneous voltage in 60-Hz AC equal ![]() ? (b)

? (b) ![]() ?

?

Glossary

- direct current

- (DC) the flow of electric charge in only one direction

- alternating current

- (AC) the flow of electric charge that periodically reverses direction

- AC voltage

- voltage that fluctuates sinusoidally with time, expressed as V = V0 sin 2πft, where V is the voltage at time t, V0 is the peak voltage, and f is the frequency in hertz

- AC current

- current that fluctuates sinusoidally with time, expressed as I = I0 sin 2πft, where I is the current at time t, I0 is the peak current, and f is the frequency in hertz

- rms current

- the root mean square of the current,

, where I0 is the peak current, in an AC system

, where I0 is the peak current, in an AC system

- rms voltage

- the root mean square of the voltage,

, where V0 is the peak voltage, in an AC system

, where V0 is the peak voltage, in an AC system

Solutions

Problem Exercises

2: 480 V

4: 2.50 ms

6: (a) 4.00 kA

(b) 16.0 MW

(c) 16.0%

8: 2.40 kW

10: (a) 4.0

(b) 0.50

(c) 4.0

12: (a) 1.39 ms

(b) 4.17 ms

(c) 8.33 ms