Chapter 26 Vision and Optical Instruments

26.4 Microscopes

Summary

- Investigate different types of microscopes.

- Learn how image is formed in a compound microscope.

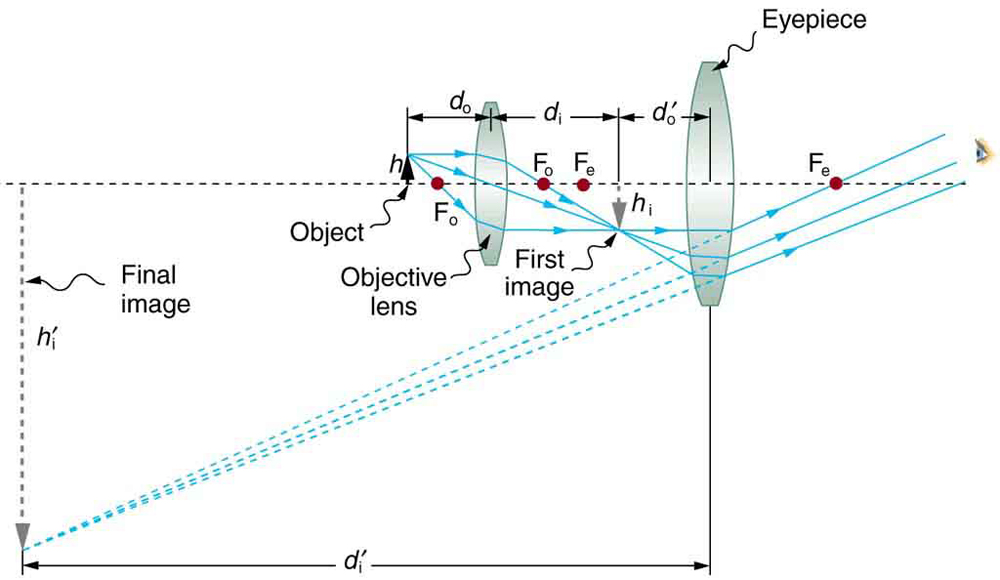

Although the eye is marvelous in its ability to see objects large and small, it obviously has limitations to the smallest details it can detect. Human desire to see beyond what is possible with the naked eye led to the use of optical instruments. In this section we will examine microscopes, instruments for enlarging the detail that we cannot see with the unaided eye. The microscope is a multiple-element system having more than a single lens or mirror. (See Figure 1) A microscope can be made from two convex lenses. The image formed by the first element becomes the object for the second element. The second element forms its own image, which is the object for the third element, and so on. Ray tracing helps to visualize the image formed. If the device is composed of thin lenses and mirrors that obey the thin lens equations, then it is not difficult to describe their behavior numerically.

Microscopes were first developed in the early 1600s by eyeglass makers in The Netherlands and Denmark. The simplest compound microscope is constructed from two convex lenses as shown schematically in Figure 2. The first lens is called the objective lens, and has typical magnification values from ![]() to

to ![]() . In standard microscopes, the objectives are mounted such that when you switch between objectives, the sample remains in focus. Objectives arranged in this way are described as parfocal. The second, the eyepiece, also referred to as the ocular, has several lenses which slide inside a cylindrical barrel. The focusing ability is provided by the movement of both the objective lens and the eyepiece. The purpose of a microscope is to magnify small objects, and both lenses contribute to the final magnification. Additionally, the final enlarged image is produced in a location far enough from the observer to be easily viewed, since the eye cannot focus on objects or images that are too close.

. In standard microscopes, the objectives are mounted such that when you switch between objectives, the sample remains in focus. Objectives arranged in this way are described as parfocal. The second, the eyepiece, also referred to as the ocular, has several lenses which slide inside a cylindrical barrel. The focusing ability is provided by the movement of both the objective lens and the eyepiece. The purpose of a microscope is to magnify small objects, and both lenses contribute to the final magnification. Additionally, the final enlarged image is produced in a location far enough from the observer to be easily viewed, since the eye cannot focus on objects or images that are too close.

To see how the microscope in Figure 2 forms an image, we consider its two lenses in succession. The object is slightly farther away from the objective lens than its focal length ![]() , producing a case 1 image that is larger than the object. This first image is the object for the second lens, or eyepiece. The eyepiece is intentionally located so it can further magnify the image. The eyepiece is placed so that the first image is closer to it than its focal length

, producing a case 1 image that is larger than the object. This first image is the object for the second lens, or eyepiece. The eyepiece is intentionally located so it can further magnify the image. The eyepiece is placed so that the first image is closer to it than its focal length ![]() . Thus the eyepiece acts as a magnifying glass, and the final image is made even larger. The final image remains inverted, but it is farther from the observer, making it easy to view (the eye is most relaxed when viewing distant objects and normally cannot focus closer than 25 cm). Since each lens produces a magnification that multiplies the height of the image, it is apparent that the overall magnification

. Thus the eyepiece acts as a magnifying glass, and the final image is made even larger. The final image remains inverted, but it is farther from the observer, making it easy to view (the eye is most relaxed when viewing distant objects and normally cannot focus closer than 25 cm). Since each lens produces a magnification that multiplies the height of the image, it is apparent that the overall magnification ![]() is the product of the individual magnifications:

is the product of the individual magnifications:

where ![]() is the magnification of the objective and

is the magnification of the objective and ![]() is the magnification of the eyepiece. This equation can be generalized for any combination of thin lenses and mirrors that obey the thin lens equations.

is the magnification of the eyepiece. This equation can be generalized for any combination of thin lenses and mirrors that obey the thin lens equations.

Overall Magnification

The overall magnification of a multiple-element system is the product of the individual magnifications of its elements.

Microscope Magnification

Calculate the magnification of an object placed 6.20 mm from a compound microscope that has a 6.00 mm focal length objective and a 50.0 mm focal length eyepiece. The objective and eyepiece are separated by 23.0 cm.

Strategy and Concept

This situation is similar to that shown in Figure 2. To find the overall magnification, we must find the magnification of the objective, then the magnification of the eyepiece. This involves using the thin lens equation.

Solution

The magnification of the objective lens is given as

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the object and image distances, respectively, for the objective lens as labeled in Figure 2. The object distance is given to be

are the object and image distances, respectively, for the objective lens as labeled in Figure 2. The object distance is given to be ![]() , but the image distance didi is not known. Isolating

, but the image distance didi is not known. Isolating ![]() , we have

, we have

where ![]() is the focal length of the objective lens. Substituting known values gives

is the focal length of the objective lens. Substituting known values gives

We invert this to find ![]() :

:

Substituting this into the expression for ![]() gives

gives

Now we must find the magnification of the eyepiece, which is given by

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the image and object distances for the eyepiece (see Figure 2). The object distance is the distance of the first image from the eyepiece. Since the first image is 186 mm to the right of the objective and the eyepiece is 230 mm to the right of the objective, the object distance is

are the image and object distances for the eyepiece (see Figure 2). The object distance is the distance of the first image from the eyepiece. Since the first image is 186 mm to the right of the objective and the eyepiece is 230 mm to the right of the objective, the object distance is ![]() . This places the first image closer to the eyepiece than its focal length, so that the eyepiece will form a case 2 image as shown in the figure. We still need to find the location of the final image

. This places the first image closer to the eyepiece than its focal length, so that the eyepiece will form a case 2 image as shown in the figure. We still need to find the location of the final image ![]() in order to find the magnification. This is done as before to obtain a value for

in order to find the magnification. This is done as before to obtain a value for ![]() :

:

Inverting gives

The eyepiece’s magnification is thus

So the overall magnification is

Discussion

Both the objective and the eyepiece contribute to the overall magnification, which is large and negative, consistent with Figure 2, where the image is seen to be large and inverted. In this case, the image is virtual and inverted, which cannot happen for a single element (case 2 and case 3 images for single elements are virtual and upright). The final image is 367 mm (0.367 m) to the left of the eyepiece. Had the eyepiece been placed farther from the objective, it could have formed a case 1 image to the right. Such an image could be projected on a screen, but it would be behind the head of the person in the figure and not appropriate for direct viewing. The procedure used to solve this example is applicable in any multiple-element system. Each element is treated in turn, with each forming an image that becomes the object for the next element. The process is not more difficult than for single lenses or mirrors, only lengthier.

Normal optical microscopes can magnify up to ![]() with a theoretical resolution of

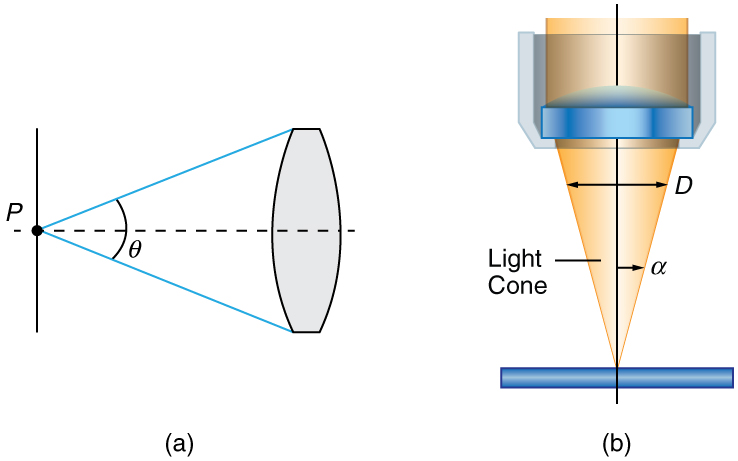

with a theoretical resolution of ![]() . The lenses can be quite complicated and are composed of multiple elements to reduce aberrations. Microscope objective lenses are particularly important as they primarily gather light from the specimen. Three parameters describe microscope objectives: the numerical aperture (

. The lenses can be quite complicated and are composed of multiple elements to reduce aberrations. Microscope objective lenses are particularly important as they primarily gather light from the specimen. Three parameters describe microscope objectives: the numerical aperture (![]() ), the magnification (

), the magnification (![]() ), and the working distance. The NA is related to the light gathering ability of a lens and is obtained using the angle of acceptance

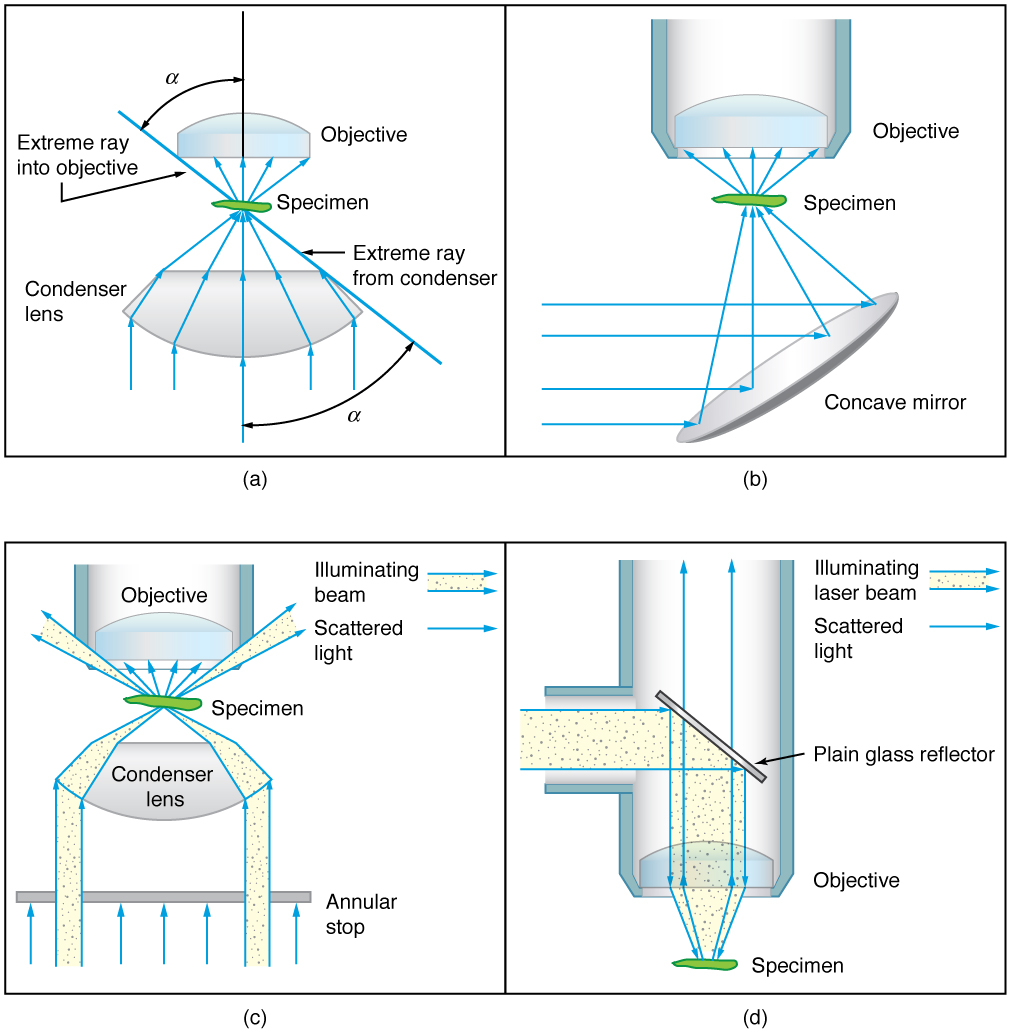

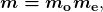

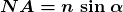

), and the working distance. The NA is related to the light gathering ability of a lens and is obtained using the angle of acceptance ![]() formed by the maximum cone of rays focusing on the specimen (see Figure 3(a)) and is given by

formed by the maximum cone of rays focusing on the specimen (see Figure 3(a)) and is given by

where ![]() is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and the specimen and

is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and the specimen and ![]() . As the angle of acceptance given by

. As the angle of acceptance given by ![]() increases,

increases, ![]() becomes larger and more light is gathered from a smaller focal region giving higher resolution. A

becomes larger and more light is gathered from a smaller focal region giving higher resolution. A ![]() objective gives more detail than a

objective gives more detail than a ![]() objective.

objective.

While the numerical aperture can be used to compare resolutions of various objectives, it does not indicate how far the lens could be from the specimen. This is specified by the “working distance,” which is the distance (in mm usually) from the front lens element of the objective to the specimen, or cover glass. The higher the ![]() the closer the lens will be to the specimen and the more chances there are of breaking the cover slip and damaging both the specimen and the lens. The focal length of an objective lens is different than the working distance. This is because objective lenses are made of a combination of lenses and the focal length is measured from inside the barrel. The working distance is a parameter that microscopists can use more readily as it is measured from the outermost lens. The working distance decreases as the

the closer the lens will be to the specimen and the more chances there are of breaking the cover slip and damaging both the specimen and the lens. The focal length of an objective lens is different than the working distance. This is because objective lenses are made of a combination of lenses and the focal length is measured from inside the barrel. The working distance is a parameter that microscopists can use more readily as it is measured from the outermost lens. The working distance decreases as the ![]() and magnification both increase.

and magnification both increase.

The term ![]() in general is called the

in general is called the ![]() -number and is used to denote the light per unit area reaching the image plane. In photography, an image of an object at infinity is formed at the focal point and the

-number and is used to denote the light per unit area reaching the image plane. In photography, an image of an object at infinity is formed at the focal point and the ![]() -number is given by the ratio of the focal length

-number is given by the ratio of the focal length ![]() of the lens and the diameter

of the lens and the diameter ![]() of the aperture controlling the light into the lens (see Figure 3(b)). If the acceptance angle is small the

of the aperture controlling the light into the lens (see Figure 3(b)). If the acceptance angle is small the ![]() of the lens can also be used as given below.

of the lens can also be used as given below.

As the ![]() -number decreases, the camera is able to gather light from a larger angle, giving wide-angle photography. As usual there is a trade-off. A greater

-number decreases, the camera is able to gather light from a larger angle, giving wide-angle photography. As usual there is a trade-off. A greater ![]() means less light reaches the image plane. A setting of

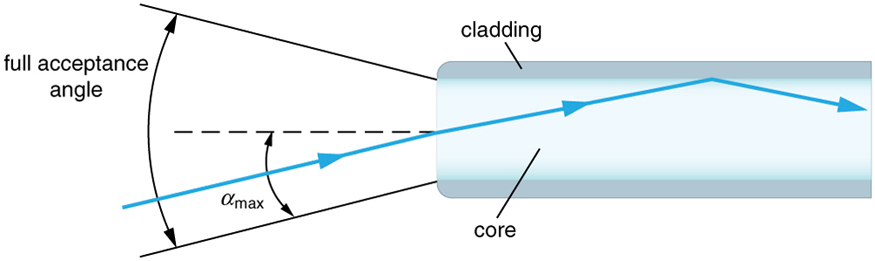

means less light reaches the image plane. A setting of ![]() usually allows one to take pictures in bright sunlight as the aperture diameter is small. In optical fibers, light needs to be focused into the fiber. Figure 4 shows the angle used in calculating the

usually allows one to take pictures in bright sunlight as the aperture diameter is small. In optical fibers, light needs to be focused into the fiber. Figure 4 shows the angle used in calculating the ![]() of an optical fiber.

of an optical fiber.

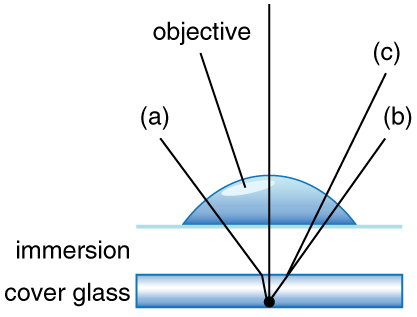

Can the ![]() be larger than 1.00? The answer is ‘yes’ if we use immersion lenses in which a medium such as oil, glycerine or water is placed between the objective and the microscope cover slip. This minimizes the mismatch in refractive indices as light rays go through different media, generally providing a greater light-gathering ability and an increase in resolution. Figure 5 shows light rays when using air and immersion lenses.

be larger than 1.00? The answer is ‘yes’ if we use immersion lenses in which a medium such as oil, glycerine or water is placed between the objective and the microscope cover slip. This minimizes the mismatch in refractive indices as light rays go through different media, generally providing a greater light-gathering ability and an increase in resolution. Figure 5 shows light rays when using air and immersion lenses.

When using a microscope we do not see the entire extent of the sample. Depending on the eyepiece and objective lens we see a restricted region which we say is the field of view. The objective is then manipulated in two-dimensions above the sample to view other regions of the sample. Electronic scanning of either the objective or the sample is used in scanning microscopy. The image formed at each point during the scanning is combined using a computer to generate an image of a larger region of the sample at a selected magnification.

When using a microscope, we rely on gathering light to form an image. Hence most specimens need to be illuminated, particularly at higher magnifications, when observing details that are so small that they reflect only small amounts of light. To make such objects easily visible, the intensity of light falling on them needs to be increased. Special illuminating systems called condensers are used for this purpose. The type of condenser that is suitable for an application depends on how the specimen is examined, whether by transmission, scattering or reflecting. See Figure 6 for an example of each. White light sources are common and lasers are often used. Laser light illumination tends to be quite intense and it is important to ensure that the light does not result in the degradation of the specimen.

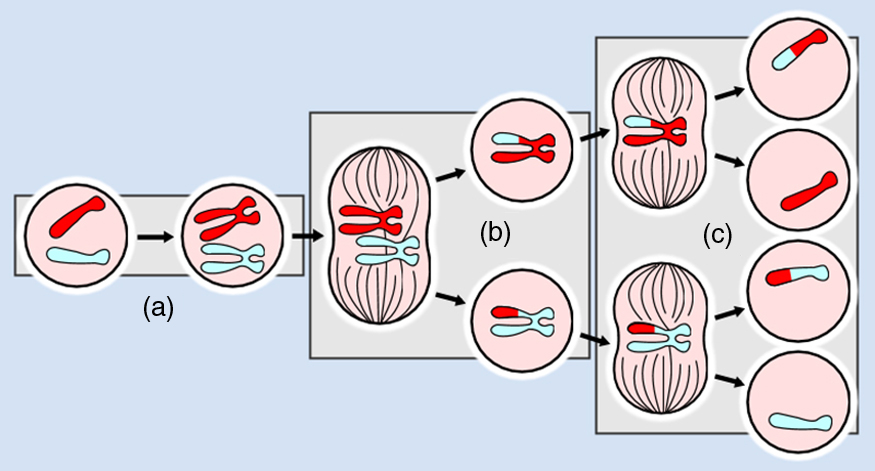

We normally associate microscopes with visible light but x ray and electron microscopes provide greater resolution. The focusing and basic physics is the same as that just described, even though the lenses require different technology. The electron microscope requires vacuum chambers so that the electrons can proceed unheeded. Magnifications of 50 million times provide the ability to determine positions of individual atoms within materials. An electron microscope is shown in Figure 7. We do not use our eyes to form images; rather images are recorded electronically and displayed on computers. In fact observing and saving images formed by optical microscopes on computers is now done routinely. Video recordings of what occurs in a microscope can be made for viewing by many people at later dates. Physics provides the science and tools needed to generate the sequence of time-lapse images of meiosis similar to the sequence sketched in Figure 8.

Take-Home Experiment: Make a Lens

Look through a clear glass or plastic bottle and describe what you see. Now fill the bottle with water and describe what you see. Use the water bottle as a lens to produce the image of a bright object and estimate the focal length of the water bottle lens. How is the focal length a function of the depth of water in the bottle?

Section Summary

- The microscope is a multiple-element system having more than a single lens or mirror.

- Many optical devices contain more than a single lens or mirror. These are analysed by considering each element sequentially. The image formed by the first is the object for the second, and so on. The same ray tracing and thin lens techniques apply to each lens element.

- The overall magnification of a multiple-element system is the product of the magnifications of its individual elements. For a two-element system with an objective and an eyepiece, this is

where

is the magnification of the objective and

is the magnification of the objective and  is the magnification of the eyepiece, such as for a microscope.

is the magnification of the eyepiece, such as for a microscope. - Microscopes are instruments for allowing us to see detail we would not be able to see with the unaided eye and consist of a range of components.

- The eyepiece and objective contribute to the magnification. The numerical aperture (

) of an objective is given by

) of an objective is given by

where

is the refractive index and

is the refractive index and  the angle of acceptance.

the angle of acceptance. - Immersion techniques are often used to improve the light gathering ability of microscopes. The specimen is illuminated by transmitted, scattered or reflected light though a condenser.

- The

describes the light gathering ability of a lens. It is given by

describes the light gathering ability of a lens. It is given by

Conceptual Questions

1: Geometric optics describes the interaction of light with macroscopic objects. Why, then, is it correct to use geometric optics to analyse a microscope’s image?

2: The image produced by the microscope in Figure 2 cannot be projected. Could extra lenses or mirrors project it? Explain.

3: Why not have the objective of a microscope form a case 2 image with a large magnification? (Hint: Consider the location of that image and the difficulty that would pose for using the eyepiece as a magnifier.)

4: What advantages do oil immersion objectives offer?

5: How does the ![]() of a microscope compare with the

of a microscope compare with the ![]() of an optical fiber?

of an optical fiber?

Problem Exercises

1: A microscope with an overall magnification of 800 has an objective that magnifies by 200. (a) What is the magnification of the eyepiece? (b) If there are two other objectives that can be used, having magnifications of 100 and 400, what other total magnifications are possible?

2: (a) What magnification is produced by a 0.150 cm focal length microscope objective that is 0.155 cm from the object being viewed? (b) What is the overall magnification if an ![]() eyepiece (one that produces a magnification of 8.00) is used?

eyepiece (one that produces a magnification of 8.00) is used?

3: (a) Where does an object need to be placed relative to a microscope for its 0.500 cm focal length objective to produce a magnification of ![]() ? (b) Where should the 5.00 cm focal length eyepiece be placed to produce a further fourfold (4.00) magnification?

? (b) Where should the 5.00 cm focal length eyepiece be placed to produce a further fourfold (4.00) magnification?

4: You switch from a ![]() oil immersion objective to a

oil immersion objective to a ![]() oil immersion objective. What are the acceptance angles for each? Compare and comment on the values. Which would you use first to locate the target area on your specimen?

oil immersion objective. What are the acceptance angles for each? Compare and comment on the values. Which would you use first to locate the target area on your specimen?

5: An amoeba is 0.305 cm away from the 0.300 cm focal length objective lens of a microscope. (a) Where is the image formed by the objective lens? (b) What is this image’s magnification? (c) An eyepiece with a 2.00 cm focal length is placed 20.0 cm from the objective. Where is the final image? (d) What magnification is produced by the eyepiece? (e) What is the overall magnification? (See Figure 3.)

6: You are using a standard microscope with a ![]() objective and switch to a

objective and switch to a ![]() objective. What are the acceptance angles for each? Compare and comment on the values. Which would you use first to locate the target area on of your specimen? (See Figure 3.)

objective. What are the acceptance angles for each? Compare and comment on the values. Which would you use first to locate the target area on of your specimen? (See Figure 3.)

7: Unreasonable Results

Your friends show you an image through a microscope. They tell you that the microscope has an objective with a 0.500 cm focal length and an eyepiece with a 5.00 cm focal length. The resulting overall magnification is 250,000. Are these viable values for a microscope?

Glossary

- compound microscope

- a microscope constructed from two convex lenses, the first serving as the ocular lens(close to the eye) and the second serving as the objective lens

- objective lens

- the lens nearest to the object being examined

- eyepiece

- the lens or combination of lenses in an optical instrument nearest to the eye of the observer

- numerical aperture

- a number or measure that expresses the ability of a lens to resolve fine detail in an object being observed. Derived by mathematical formula

where

is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and the specimen and

is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and the specimen and

Solutions

Problem Exercises

1: (a) 4.00

(b) 1600

3: (a) 0.501 cm

(b) Eyepiece should be 204 cm behind the objective lens.

5: (a) +18.3 cm (on the eyepiece side of the objective lens)

(b) -60.0

(c) -11.3 cm (on the objective side of the eyepiece)

(d) +6.67

(e) -400