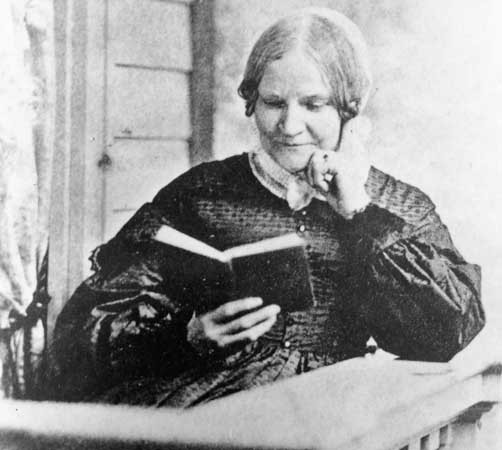

Lydia Marie Childs

Selections from Letters From New York & John Brown correspondence

Introduction

In a letter to Mrs. J.C. Mason, Lydia Maria Child writes:

“Literary popularity was never a paramount object with me, even in my youth; and, now that I am old, I am utterly indifferent to it.”

The passage above is Lydia Maria Child’s response to a letter she received from Mrs. J.C. Mason. Child had come to the defense of the abolitionist John Brown (his intent, not his methods), and Mason’s letter was a harsh critique of Child’s position. Mason was so outraged by Child’s defense that she ended her letter by saying that “no Southerner ought [..] to read a line of your composition, or to touch a magazine which bears your name in its list of contributors.”

It was that sentence that prompted Child’s response above. Child’s interest in activist causes put her on the unpopular side of nearly every social debate of the period. As she indicates in her letter, her writing was not aimed at “literary popularity;” instead, her writing was geared at correcting injustice wherever she saw it. Child tackled slavery, Indian Removal policy and Native American discrimination, prison reform, women’s rights, poverty, and children’s issues. She was a prolific writer: she wrote short stories, novels, essays, and domestic manuals; edited journals; and assisted Harriet Jacobs with the publication of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Given this broad spectrum, her outspokenness, and her commitment to social justice, Child’s response to Mason seems almost obvious.

Discussion Questions:

- Consider Child’s work alongside other “Age of Reform” writers like Fanny Fern, Harriet Jacobs, or Henry David Thoreau. How do you see her work extending theirs? In what ways does it seem she is engaged in conversation with them?

- How does Child define justice?

- Consider how Child frames her arguments. What kinds of evidence does she use? Where do you find her especially compelling or persuasive?

- How does Child seem to define what counts as American? What does she suggest are ideal American values?

LETTER XXXIY.

woman’s rights. January, 1843.

You ask what are my opinions about “Woman’s Rights.” I confess a strong distaste to the subject, as it has been generally treated. On no other theme, probably, has there been uttered so much of false, mawkish sentiment, shallow philosophy, and sputtering, farthing-candle wit. If the style of its advocates has often been ofiensive to taste, and unacceptable to reason, assuredly that of its opponents have been still more so. College boys have amused themselves with writing dreams, in

which they saw women in hotels, with their feet hoisted, and chairs tilted back, or growling and bickering at each other in legislative halls, or fighting at the polls, with eyes blackened by fisticuffs. But it never seems to have occurred to these facetious writers, that the proceedings which appear so ludicrous and improper in women are also ridiculous and disgraceful in men. It were well that men should learn not to hoist their feet above their heads, and tilt their chairs backward, not to growl and snap in the halls of legislation, or give each other black eyes at the polls.

Maria Edge worth says, ” We are disgusted when we see a woman’s mind overwhelmed with a torrent of learning; that the tide of literature has passed over it should be betrayed only by its fertility.” This is beautiful and true; but is it not likewise applicable to man? The truly great never seek to display themselves. If they carry their heads high above the crowd, it is only made manifest to others by accidental revelations of their extended vision. ” Human duties and proprieties do not lie so very far apart/’ said Harriet Martineau; ” if they did, there would be two gospels and two teachers, one for man and another for woman.”

It would seem, indeed, as if men were willing to give women exclusive benefit of gospel-teaching. ” Women should be gentle,” say the advocates of subordination; but when Christ said,” Blessed are the meek,” did he preach to women only ] ” Girls should be modest,” is the language of common teaching, continually uttered in Avords and customs. Would it not be an improvement for men, also, to be scrupulously pure in manners, conversation and life ? Books addressed to young married people abound with advice to the wife, to control her temper, and never to utter wearisome complaints, or vexatious words, when the husband comes home fretful or unreasonable from his out-of-door conflicts with the world. Would not the advice be as excellent and appropriate, if the husband were advised to conquer his fretfulness, and forbear his complaints, in consideration of his wife’s ill-health, fatiguing cares, and the thousand disheartening influences of domestic routine] In short, whatsoever can be named as loveliest, best, and most graceful in woman, would likewise be good and graceful in man. You will perhaps remind me of courage 1 If you use the word in its highest signification, I answer that woman, above others, hath abundant need of it in her pilgrimage; and the true woman wears it with a quiet grace. If you mean mere animal courage, that is not mentioned in the sermon on the Mount, among those qualities which enable us to inherit the earth, or become the children of God. That the feminine ideal approaches much nearer to the gospel standard, than the prevalent idea of manhood is shown by the universal tendency to represent the Saviour and his most beloved disciple with mild, meek expression, and feminine beauty. None speak of the bravery, the might, or the intellect of Jesus; but the devil is always imagined as a being of acute intellect, political cunning, and the fiercest courage. These universal and instinctive tendencies of the human mind reveal much.

That the present position of women in society is the result of physical force is obvious enough; whosoever doubts it, let her reflect why she is afraid to go out in the evening without the protection of a man. What constitutes the danger of aggression ? Superior physical strength, uncontrolled by the moral sentiments. If physical strength were in complete subjection to moral influence, there would be no need of outward protection. That animal instinct and brute force now govern the world, is painfully apparent in the condition of women everywhere; from the Morduan Tartars, whose ceremony of marriage consists in placing the bride on a mat, and consigning her to the bride- groom, with the words, ” Here, wolf, take thy lamb,” — to the German remark, that ” stiff ale, stinging tobacco, and a girl in her smart dress, are the best things.” The same sentiment, softened by the refinements of civilisation, peeps out in Stephen’s remark, that ” woman never looks so interesting, as when leaning on the arm of a soldier:” and in Hazlitt’s complaint that “it is not easy to keep up a conversation with women in company. It is thought a piece of rudeness to differ from them; it is not quite fair to ask them a reason for what they say.”

This sort of politeness to women is what men call gallantry; an odious word to every sensible woman, because she sees that it is merely the flimsy veil which foppery throws over sensuality, to conceal its grossness. So far is it from indicating sincere esteem and affection for woman, that the profligacy of a nation may, in general, be fairly measured by its gallantry. This taking away rights, and condescending to grant privileges, is an old trick of the physical force principle; and with the immense majority, who only look on the surface of things, this mask effectually disguises an ugliness, which would otherwise be abhorred. The most inveterate slaveholders were those who took most pride in dressing their household servants handsomely, and who would be most ashamed to have the name of being unnecessarily cruel. And profligates, who form the lowest and most sensual estimate of women, are the very ones to treat them with an excess of outward deference.

There are few books which I can read through without feeling insulted as a woman; but this insult is almost universally conveyed through that which was intended for praise. Just imagine, for a moment, what impression it would make on men, if women authors should write about their ” rosy lips, ” and ” melting eyes, ” and ” voluptuous forms, ” as they write about us ! That women in general do not feel this kind of flattery to to be an insult, I readily admit; for in the first place, they do not perceive the gross chattel-principle of which it is the utterance; moreover, they have, from long habit, become accustomed to consider themselves as household conveniences, or gilded toys.

Hence, they consider it feminine and pretty to adjure all such use of their faculties as would make them co-workers with man in the advancement of those great principles, on which the pro- gress of society depends. ” There is perhaps no animal, ” says Hannah More, “so much indebted to subordination, for its good behaviour, as woman. ” Alas, for the animal age, in which such utterance could be tolerated by public sentiment !

Martha More, sister of Hannah, describing a very impressive scene at the funeral of one of her Charity School teachers, says, ” The spirit within me seemed struggling to speak, and I was in a sort of agony; but I recollected that I had heard, some- where, a woman must not speak in the church. Oh, had she been buried in the church-yard, a messenger from Mr. Pitt himself should not have restrained me; for I seemed to have received a message from a higher Master within, seeking utterance.”

This application of theological teaching carries its own commentary.

I have said enough to show that I consider prevalent opinions and customs highly unfavourable to the moral and intellectual development of women : and I need not say, that, in proportion to their true culture, women will be more useful and happy, and domestic life more perfected. True culture in them, as in men, consists in the full and free development of individual character, regulated by their own perceptions of what is true, and their own love of what is good.

This individual responsibility is rarely acknowledged, even by the most refined, as necessary to the spiritual progress of women. I once heard a very beautiful lecture from R. W. Emerson, on Being and Seeming. In the course of many remarks, as true as they were graceful, he urged women to be, rather than seem. He told them that all their laboured education of forms, strict observance of genteel etiquette, tasteful arrangement of the toilette, &c., all this seeming would not gain hearts like being truly what God made them; that earnest simplicity, the sincerity of nature, would kindle the eye, light up the countenance, and give an inexpressible charm to the plainest features.

The advice was excellent, but the motive, by which it was urged, brought a flush of indignation over my face. Men were exhorted to be, rather than to seem, that they might fulfil the sacred mission for which their souls were embodied; that they might, in God’s freedom, grow up into the full stature of spiritual manhood; but women were urged to simplicity and truthfulness, that they might become more pleasing.

Are we not all immortal beings’? Is not each one responsible for himself and herself? There is no measuring the mischief done by the prevailing tendency to teach women to be virtuous as a duty to man, rather than to God — for the sake of pleasing the creature, rather than the Creator. “God is thy law, thou mine,” said Eve to Adam. May Milton be forgiven for sending that thought ”out into everlasting time” in such a jewelled setting. What weakness, vanity, frivolity, infirmity of moral purpose, sinful flexibility of principle — in a word, what soulstifling, has been the result of thus putting man in the place of God!

But while I see plainly that society is on a false foundation, and that prevailing views concerning women indicate the want of wisdom and purity, which they serve to perpetuate — still, I must acknowledge that much of the talk about women’s rights offends both my reason and my taste. I am not of those who maintain there is no sex in souls; nor do I like the results deducible from that doctrine. Kinmont, in his admirable book, called the Natural History of Man, speaking of the warlike courage of the ancient German women, and of their being respectfully consulted on important public affairs, says, “You ask me if I consider all this right, and deserving of approbation; or that women were here engaged in their appropriate tasks’? I answer, yes; it is just as right that they should take this interest in the honour of their country, as the other sex. Of course, I do not think that women were made for war and battle; neither do I believe that men were. But since the fashion of the times had made it so, and settled it that war was a necessary element of greatness, and that no safety was to be procured without it, I argue that it shows a healthful state of feeling in other respects, that the feelings of both sexes were equally enlisted in the cause; that there was no division in the house, or the state; and that the serious pursuits and objects of the one were also the serious pursuits and objects of the other.”

The nearer society approaches to divine order, the less separation will there be in the characters, duties, and pursuits of men and women. Women will not become less gentle and graceful, but men will become more so. Women will not neglect the care and education of their children, but men will find themselves ennobled and refined by sharing those duties with them; and will receive, in return, co-operation and sympathy in the discharge of various other duties, now deemed inappropriate to women. The more women become rational companions, partners in business and in thought, as well as in afiection and amusement, the more highly will men appreciate home — that blessed word, which opens to the human heart the most perfect glimpse of Heaven, and helps to carry it thither, as on an angel’s wings.

“Domestic bliss, That can, the world eluding, be itself A world enjoyed; that wants no witnesses But its own sharers, and approving heaven; That, like a flower deep hid in rocky cleft, Smiles, though ’tis looking only at the sky.”

Alas for these days of palatial houses where families exchange comforts for costliness, fireside retirement for flirtation and flaunting, and the simple, healthful, cozy meal, for gravies and gout, dainties and dyspepsia! There is no characteristic of my countrymen which I regret so deeply, as their slight degree of adhesiveness to home. Closely intertwined with this instinct, is the religion of a nation. The home and the church bear a near relation to each other. The French have no such word as home in their language, and I believe they are the least reverential and religious of all the Christian nations. A Frenchman had been in tlie habit of visiting a lady constantly for several years, and being alarmed at a report that she was sought in marriage, he was asked why he did not marry her himself. ” Marry her! ” exclaimed he; ” good heavens ! where should I spend my evenings “? ” The idea of domestic happiness was altogether a foreign idea to his soul, like a word that conveved no meaninof. Relimous sentiment in France leads the same roving life as the domestic affections; breakfasting at one restaurateur’s, and supping at another’s. When some wag in Boston reported that Louis-Philippe had sent over Dr. Channing to manufacture a religion for the French people, the witty significance of the joke was generally appreciated.

There is a deep spiritual reason why all that relates to the domestic affections should ever be found in close proximity with religious faith. The ago of chivalry was likewise one of un-questioning veneration, which led to the crusade for the holy sepulchre.

The French Revolution, which tore down churches, and voted that there was no God, likewise annulled marriage; and the doctrine that there is no sex in souls has usually been urged by those of infidel tendencies. Carlyle says, ” But what feeling it was in the ancient, devout, deep soul, which of marriage made a sacrament; this, of all things in the world, is what Diderot will think of for aeons without discovering; unless, perhaps, it were to increase the vestry fees.”

The conviction that woman’s present position in society is a false one, and therefore re-acts disastrously on the happiness and improvement of man, is pressing, by slow degrees, on the common consciousness, through all the obstacles of bigotry, sensuality, and selfishness. As man approaches to the truest life, he will perceive more and more that there is no separation or discord in their mutual duties. They will be one; but it will be as affection and thought are one; the treble and bass of the same harmonious tune.

LETTER Y.

January, 20, 1844.

Inquiring one day for a washerwoman, I was referred to a coloured woman, in Lispenard Street, by the name of Charity Bowery. I found her a person of uncommon intelligence, and great earnestness of manner.

In answer to my enquiries, she told me her history, which I will endeavour to relate precisely in her own words. Unfortunately, I cannot give the highly dramatic effect it received from her expressive intonations, and rapid variations of countenance.

With the exception of some changes of names, I repeat, with perfect accuracy, what she said, as follows : —

” I am about sixty-five years old, I was born near Edenton, North Carolina. My master was very kind to his slaves. If an overseer whipped them, he turned him away. He used to whip them himself sometimes, with hickory switches as large as my little finger. My mother nursed all his children. She was reckoned a very good servant; and our mistress made it a point to give one of my mother’s children to each of her own.. I fell to the lot of Elizabeth, her second daughter. It was my business to wait upon her. Oh, my old mistress was a kind woman. She was all the same as a mother to poor Charity. If Charity wanted to learn to spin, she let her learn; if Charity wanted to learn to knit, she let her learn; if Charity wanted to learn to weave, she let her learn. I had a wedding when I was married; for mistress didn’t like to have her people take up with one another, without any minister to marry them. When my dear good mistress died, she charged her children never to separate me and my husband; ‘ For,’ said she, ‘ if ever there was a match made in heaven, it was Charity and her husband.’ My husband was a nice good man; and mistress knew we set stores by one another. Her children promised they never would separate me from my husband and children. Indeed, they used to tell me they would never sell me at all y and I am sure they meant what they said. But my young master got into trouble. He used to come home and sit lean- ing his head on his hand by the hour together, without speaking to any body. I see something was the matter; and I begged of him to tell me what made him look so worried. He told me he owed seventeen hundred dollars, that he could not pay; and he was afraid he should have to go to prison. I begged him to sell me and my children, rather than to go to jail. I see the tears come into his eyes. ‘ I don’t know, Charity,’ said lie; ‘ I’ll see what can be done. One thing you may feel easy about; I will never separate you from your husband and chil-dren, let what will come.’

” Two or three days after, he came to me, and says he;’ Charity, how should you be liked to be sold to Mr. Kinmore?’ I told him I would rather be sold to him than to any body else, because my husband belonged to him. My husband was a nice good man, and we set stores by one another. Mr. Kinmore agreed to buy us; and so I and my children went there to live. He was a kind master; but as for mistress Kinmore, she was a devil? Mr. Kinmore died a few years after he bought us; and in his will he give me and my husband free; but I never knowed anything about it, for years afterward. I don’t know how they managed it. My poor husband died, and never knowed that he was free. But it’s all the same now. He’s among the ransomed. He used to say, ‘ Thank God, it’s only a little way home; I shall soon be with Jesus.’ Oh, he had a fine old Cliristian heart.”

Here the old woman sighed deeply, and remained silent for a moment, while her right hand slowly rose and fell upon her lap, as if her thoughts were mournfully busy. At last she resumed.

” Sixteen children I’ve had, first and last; and twelve I’ve nursed for mistress. From the time my first baby was born, I always set my heart upon buying freedom for some of my children. I thought it was of more consequence to them, than to me; for I was old, and used to be a slave. But mistress Kinmore wouldn’t let me have my children. One after another — one after another — she sold ’em away from me. Oh, how many times that woman’s broke my heart !”

Here her voice choked, and the tears began to flow. She wiped them quickly with the corner of her apron, and con- tinued : ” I tried every way I could, to lay up a copper to buy my children; but I found it pretty hard; for mistress kept me at work all the time. It was ‘ Charity ! Charity ! Charity ! ‘ from morning till night. ‘ Charity, do this,’ and ‘ Charity, do that.’

” I used to do the washings of the family; and large washings they were. The public road run right by my little hut; and I thought to myself, while I stood there at the wash-tub, I might, just as well as not, be earning something to buy my children. So I set up a little oyster- board; and when any-body come along, that wanted a few oysters and a cracker, I left my wash-tub and waited upon him. When I got a little money laid up, I went to my mistress and tried to buy one of my children. She knew how long my heart had been set upon it, and how hard I had worked for it. But she wouldn’t let me have one ! — She wouldn’t let me have one ! So, I went to work again; and set up late o’ nights, in hopes I could earn enough to tempt her. When I had two hundred dollars, I went to her again; but she thought she could find a better market, and she wouldn’t let me have one. At last, what did you think that woman did? She sold me and five of my children to the speculators ! Oh, how I did feel, when I heard my children was sold to the speculators ! ”

I knew very well that by speculators the poor mother meant men whose trade it is to buy up coffles of slaves, as they buy cattle for the market.

After a short pause, her face brightened up, and her voice suddenly changed to a gay and sprightly tone.

” Surely, ma’am, there’s always some good comes of being kind to folks. While I kept my oyster-board, there was a thin, peaked-looking man, used to come and buy of me. Some- times he would say, ‘ Aunt Charity (he always called me Aunt Charity), you must fix me up a nice little mess, for I feel poor- ly to-day.’ I always made something good for him; and if he didn’t happen to have any change, I always trusted him. He liked my messes mighty well. — Now, who do you think that should turn out to be, but the very speculator that bought me ! He come to me, and says he, ‘ Aunt Charity (he always called me Aunt Charity), you’ve been very good to me, and fixed me up many a nice little mess, when I’ve been poorly; and now you shall have your freedom for it, and I’ll give you your youngest child.'”

” That was very kind,” said I; ” but I wish he had given you all of them.”

With a look of great simplicity, and in tones of expostulation, the slave-mother replied, ” Oh, he couldn’t afford that, you know.”

” Well,” continued she, ” after that, I concluded I’d come to the Free States. But mistress had one child of mine; a boy about twelve years old. I had always set my heart upon buying Richard. He was the image of his father; and my husband was a nice a good man; and we set stores by one another.

Besides, I was always uneasy in my mind about Bichard. He was a spirity lad; and I knew it was very hard for him to be a slave. Many a time;, I have said to him, ‘ Bichard, let what will happen, never lift your hand against your master.”

” But I knew it would always be hard work for him to be a slave. I carried all my money to my mistress, and told her I had more due to me; and if all of it wasn’t enough to buy my poor boy, I’d work hard and send her all my earnings, till she said I had paid enough. She knew she could trust me. She knew Charity always kept her word. But she was a hard-hearted woman. She wouldn’t let me have my boy. With a heavy heart, I went to work to earn more, in hopes I might one day be able to buy him. To be sure, I didn’t get much more time, than I did when I was a slave; for mistress was always calling upon me; and I didn’t like to disoblige her. I wanted to keej) the right side of her, in hopes she’d let me have my boy. One day, she sent me off an errand. I had to wait some time. When I come back, mistress was counting a heap of bills in her lap. She was a rich woman, — she rolled in gold. My little girl stood behind her chair; and as mistress counted the money, — ten dollars, — twenty dollars, — fifty dollars, — I see that she kept crying. I thought may be mistress had struck her. But when I see the tears keep rolling down her cheeks all the time, I went up to her, and whispered, ‘ What’s the matter ? ‘ She pointed to mistress’s lap and said, ‘ Broder’s money! Broder’s money!’ Oh, then I understood it all ! I said to mistress Kinmore, ‘ Have you sold my boy ? ‘ Without looking up from counting her money, she drawled out, ‘ Yes, Charity; and I got a great price for him ! ‘ ” [Here the-coloured woman imitated to perfection the languid, indolent tone of Southern ladies.]

” Oh, my heart was too full ! She had sent me away of an-errand, because she didn’t Avant to be troubled with our cries. I hadn’t any chance to see my poor boy. I shall never see him -again in this world. My heart felt as if it was under a great load of lead. I couldn’t speak my feelings. I never spoke them to her, from that day to this. As I went out of the room, I lifted up my hands, and all I could say was, ‘ Mistress, how could you do it ? ‘ ”

The poor creature’s voice had grown more and more tremu-lous, as she proceeded, and was at length stifled with sobs.

After some time, she resumed her story : ” When my boy was gone, I thought I might sure enough as well go to the Free States. But mistress had a little grandchild of mine. His mother died when he was born. I thought it would be some comfort to me, if I could buy little orphan Sammy. So I carried all the money I had to my mistress again, and asked her if she would let me buy my grandson. But she wouldn’t let me have him. Then I had nothing more to wait for; so I come on to the Free States. Here I have taken in washing;, and my daughter is smart at her needle j and we get a very comfortable living.”

” Do you ever hear from any of your children?” said I.

” Yes, ma’am, I hear from one of them. Mistress Kinmore sold one to a lady, that comes to the North every summer; and she brings my daughter with her.”

” Don’t she know that it is a good chance to take her free-dom, when she is brought to the North ? ” said I.

” To be sure she knows that,^’ replied Charity, with significant emphasis. “But my daughter is pious. She’s member of a church. Her mistress knows she wouldn’t tell a lie for her right hand. She makes her promise on the Bible, that she won’t try to run away, and that she will go back to the South with her; and so, ma’am, for her honour and her Christianity’s sake, she goes back into slavery.”

” Is her mistress kind to her ? ”

” Yes, ma’am; but then everybody likes to be free. Her mistress is very kind. She says I may buy her for four hundred dollars; and that’s a low price for her, — two hundred paid down, and the rest as we can earn it. Kitty and I are trying to lay up enough to buy her.”

” What has become of your mistress Kinmore ? Do you ever hear from her ?”

” Yes, ma’am, I often hear from her; and summer before last, as I was walking up Broadway, with a basket of clean clothes, who should I meet but my old mistress Kinmore? She gave a sort of a start, and said, in her drawling way, ‘ O, Charity, is it you?’ Her voice sounded deep and hollow, as if it come from under the ground; for she was far gone in a consumption. If I wasn’t mistaken, there was a something about here (laying her hand on her heart), that made her feel strangely when she met poor Charity. Says I, ‘ How do you do, mistress Kinmore? How does little Sammy do ?’ (That was my little grandson, you know, that she wouldn’t let me buy).”

” ‘ I’m poorly, Charity, says she; ‘ very poorly, Sammy’s a smart boy. He’s grown tall, and tends table nicely. Every night I teach him his prayers.'”

The indignant grandmother drawled out the last word in a tone, which Fanny Kemble herself could not have surpassed. Then suddenly changing both voice and manner, she added, in tones of earnest dignity, ” Och ! I couldn’t stand that! Good morning, ma’am ! ” said I.

I smiled, as I inquired whether she had heard from Mrs. Kinmore, since.

“Yes, ma’am. The lady that brings my daughter to the North every summer, told me last Fall she didn’t think mistress Kinmore could live long. When she went home, she asked me if I had any message to send to my old mistress. I told her I had a message to send. Tell her, says I, to prepare to meet poor Charity at the judgment seat.”

I asked Charity if she had heard any further tidings of her scattered children. The tears came to her eyes. “I found out that my poor Richard was sold to a man in Alabama. A white gentleman, who has been very kind to me, here in New York, went to them parts lately, and brought me back news of

Richard. His master ordered him to be flogged, and he wouldn’t come up to be tied. ‘ If you don’t come up, you black rascal, I’ll shoot you,’ said his master. ‘ Shoot away,’ said Richard; ‘ I won’t come to be flogged.’ His master pointed a pistol at him, — and, — in two hours my poor boy was dead ! Richard was a spirity lad. I always knew it was hard for him to be a slave. Well, he’s free now. God be praised, he’s free now; and I shall soon be with him.” ”’ * * * *

In the course of my conversations with this interesting woman, she told me much about the patrols, who, armed with arbitrary power, and frequently intoxicated, break into the houses of the coloured people at the south, and subject them to all manner of outrages. But nothing seemed to have ex-cited her imagination so much as the insurrection of Nat Turner. The panic that prevailed throughout the Slave States on that occasion, of course, reached her ear in repeated echoes; and the reasons are obvious why it should have awakened intense interest. It was in fact a sort of Hegira to her mind, from which she was prone to date all important events in the history of her limited world.

” On Sundays,” said she, ” I have seen the negroes up in the country going away under large oaks, and in secret places, sitting in the woods, with spelling books. The brightest and best men were killed in Nat’s time. Such ones are always suspected. All the coloured folks were afraid to pray, in the time of the old Prophet Nat. There was no law about it; but the whites reported it round among themselves, that if a note was heard, we should have some dreadful punishment. After that, the low whites would fall upon any slaves they heard praying, or singing a hymn; and they often killed them, before their masters or mistresses could get to them.”

I asked Charity to give me a specimen of their slave hymns. In a voice cracked with age, but still retaining considerable sweetness, she sang : —

“A few more beatings of the wind and rain, Ere the winter will be over —

Glory, Hallelujah !

Some friends has gone before me, — I must try to go and meet them —

Glory, Hallelujah !

A few more risings and settings of the sun, Ere the winter will be over —

Glory, Hallelujah !

There’s a better day a coming — There’s a better day a coming —

Oh, Glory, Hallelujah !”

With a very arch expression, she looked up, as she con- cluded, and said, ” They wouldn’t let us sing that. They wouldn’t let us sing that. They thought we was going to rise, because we sung ‘ better days are coming.’ ”

I shall never forget poor Charity’s natural eloquence, or the spirit of Christian meekness and forbearance, which so beauti- fully characterised her expressions. She has now gone where ” the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest.”

CHAPTER VIII.

PREJUDICES AGAINST PEOPLE OF COLOR, AND OUR DUTIES IN RELATION TO THIS SUBJECT.

“A negro has a soul, an’ please your honor,” said the Corporal, (doubtingly.)

“I am not much versed, Corporal,” quoth my Uncle Toby, “In things of that kind; but I suppose God would not leave him without one any more than thee or me.”

“It would be putting one sadly over the head of the other,” quoth the Corporal.

“It would so,” said my Uncle Toby.

“Why then, an’ please your honor, is a black man to be used worse than a white one.”

“I can give no reason,” said my Uncle Toby.

“Only,” cried the Corporal, shaking his head, “because he has no one to stand up for him.”

“It is that very thing, Trim,” quoth my Uncle Toby, “which recommends him to protection.”

While we bestow our earnest disapprobation on the system of slavery, let us not flatter ourselves that we are in reality any better than our brethren of the South. Thanks to our soil and climate, and the early exertions of the excellent Society of Friends, the form of slavery does not exist among us; but the very spirit of the hateful and mischievous thing is here in all its strength. The manner in which we use what power we have, gives us ample reason to be grateful that the nature of our institutions does not intrust us with more. Our prejudice against colored people is even more inveterate than it is at the South. The planter is often attached to his negroes, and lavishes caresses and kind words upon them, as he would on a favorite hound: but our cold-hearted, ignoble prejudice admits of no exception—no intermission.

The Southerners have long continued habit, apparent interest and dreaded danger, to palliate the wrong they do; but we stand without excuse. They tell us that Northern ships and Northern capital have been engaged in this wicked business; and the reproach is true. Several fortunes in this city have been made by the sale of negro blood. If these criminal transactions are still carried on, they are done in silence and secrecy, because public opinion has made them disgraceful. But if the free States wished to cherish the system of slavery for ever, they could not take a more direct course than they now do. Those who are kind and liberal on all other subjects, unite with the selfish and the proud in their unrelenting efforts to keep the colored population in the lowest state of degradation; and the influence they unconsciously exert over children early infuses into their innocent minds the same strong feelings of contempt.

The intelligent and well-informed have the least share of this prejudice; and when their minds can be brought to reflect upon it, I have generally observed that they soon cease to have any at all. But such a general apathy prevails and the subject is so seldom brought into view, that few are really aware how oppressively the influence of society is made to bear upon this injured class of the community. When I have related facts, that came under my own observation, I have often been listened to with surprise, which gradually increased to indignation. In order that my readers may not be ignorant of the extent of this tyrannical prejudice, I will as briefly as possible state the evidence, and leave them to judge of it, as their hearts and consciences may dictate.

In the first place, an unjust law exists in this Commonwealth, by which marriages between persons of different color is pronounced illegal. I am perfectly aware of the gross ridicule to which I may subject myself by alluding to this particular; but I have lived too long, and observed too much, to be disturbed by the world’s mockery. In the first place, the government ought not to be invested with power to control the affections, any more than the consciences of citizens. A man has at least as good a right to choose his wife, as he has to choose his religion. His taste may not suit his neighbors; but so long as his deportment is correct, they have no right to interfere with his concerns. In the second place, this law is a useless disgrace to Massachusetts. Under existing circumstances, none but those whose condition in life is too low to be much affected by public opinion, will form such alliances; and they, when they choose to do so, will make such marriages, in spite of the law. I know two or three instances where women of the laboring class have been united to reputable, industrious colored men. These husbands regularly bring home their wages, and are kind to their families. If by some of the odd chances, which not unfrequently occur in the world, their wives should become heirs to any property, the children may be wronged out of it, because the law pronounces them illegitimate. And while this injustice exists with regard to honest, industrious individuals, who are merely guilty of differing from us in a matter of taste, neither the legislation nor customs of slaveholding States exert their influence against immoral connexions.

In one portion of our country this fact is shown in a very peculiar and striking manner. There is a numerous class at New-Orleans, called Quateroons, or Quadroons, because their colored blood has for several successive generations been intermingled with the white. The women are much distinguished for personal beauty and gracefulness of motion; and their parents frequently send them to France for the advantages of an elegant education. White gentlemen of the first rank are desirous of being invited to their parties, and often become seriously in love with these fascinating but unfortunate beings. Prejudice forbids matrimony, but universal custom sanctions temporary connexions, to which a certain degree of respectability is allowed, on account of the peculiar situation of the parties. These attachments often continue for years—sometimes for life—and instances are not unfrequent of exemplary constancy and great propriety of deportment.

What eloquent vituperations we should pour forth, if the contending claims of nature and pride produced such a tissue of contradictions in some other country, and not in our own!

There is another Massachusetts law, which an enlightened community would not probably suffer to be carried into execution under any circumstances; but it still remains to disgrace the statutes of this Commonwealth. It is as follows:

“No African or Negro, other than a subject of the Emperor of Morocco, or a citizen of the United States, (proved so by a certificate of the Secretary of the State of which he is a citizen,) shall tarry within this Commonwealth longer than two months; and on complaint a justice shall order him to depart in ten days; and if he do not then, the justice may commit such African or Negro to the House of Correction, there to be kept at hard labor; and at the next term of the Court of Common Pleas, he shall be tried, and if convicted of remaining as aforesaid, shall be whipped not exceeding ten lashes; and if he or she shall not then depart, such process shall be repeated, and punishment inflicted, toties quoties.” Stat. 1788, Ch. 54.

An honorable Haytian or Brazilian, who visited this country for business or information, might come under this law, unless public opinion rendered it a mere dead letter.

There is among the colored people an increasing desire for information, and laudable ambition to be respectable in manners and appearance. Are we not foolish as well as sinful, in trying to repress a tendency so salutary to themselves, and so beneficial to the community? Several individuals of this class are very desirous to have persons of their own color qualified to teach something more than mere reading and writing. But in the public schools, colored children are subject to many discouragements and difficulties; and into the private schools they cannot gain admission. A very sensible and well-informed colored woman in a neighboring town, whose family have been brought up in a manner that excited universal remark and approbation, has been extremely desirous to obtain for her eldest daughter the advantages of a private school; but she has been resolutely repulsed on account of her complexion. The girl is a very light mulatto, with great modesty and propriety of manners; perhaps no young person in the Commonwealth was less likely to have a bad influence on her associates. The clergyman respected the family, and he remonstrated with the instructer; but while the latter admitted the injustice of the thing, he excused himself by saying such a step would occasion the loss of all his white scholars.

In a town adjoining Boston, a well behaved colored boy was kept out of the public school more than a year, by vote of the trustees. His mother, having some information herself, knew the importance of knowledge, and was anxious to obtain it for her family. She wrote repeatedly and urgently; and the schoolmaster himself told me that the correctness of her spelling, and the neatness of her hand-writing, formed a curious contrast with the notes he received from many white parents. At last, this spirited woman appeared before the committee, and reminded them that her husband, having for many years paid taxes as a citizen, had a right to the privileges of a citizen; and if her claim were refused, or longer postponed, she declared her determination to seek justice from a higher source. The trustees were, of course, obliged to yield to the equality of the laws, with the best grace they could. The boy was admitted, and made good progress in his studies. Had his mother been too ignorant to know her rights, or too abject to demand them, the lad would have had a fair chance to get a living out of the State as the occupant of a workhouse, or penitentiary.

The attempt to establish a school for African girls at Canterbury, Connecticut, has made too much noise to need a detailed account in this volume. I do not know the lady who first formed the project, but I am told that she is a benevolent and religious woman. It certainly is difficult to imagine any other motives than good ones, for an undertaking so arduous and unpopular. Yet had the Pope himself attempted to establish his supremacy over that Commonwealth, he could hardly have been repelled with more determined and angry resistance. Town-meetings were held, the records of which are not highly creditable to the parties concerned. Petitions were sent to the Legislature, beseeching that no African school might be allowed to admit individuals not residing in the town where said school was established; and strange to relate, this law, which makes it impossible to collect a sufficient number of pupils, was sanctioned by the State. A colored girl, who availed herself of this opportunity to gain instruction, was warned out of town, and fined for not complying; and the instructress was imprisoned for persevering in her benevolent plan.

It was said, in excuse, that Canterbury would be inundated with vicious characters, who would corrupt the morals of the young men; that such a school would break down the distinctions between black and white; and that marriages between people of different colors would be the probable result. Yet they assumed the ground that colored people must always be an inferior and degraded class—that the prejudice against them must be eternal; being deeply founded in the laws of God and nature. Finally, they endeavored to represent the school as one of the incendiary proceedings of the Anti-Slavery Society; and they appealed to the Colonization Society, as an aggrieved child is wont to appeal to its parent.

The objection with regard to the introduction of vicious characters into a village, certainly has some force; but are such persons likely to leave cities for a quiet country town, in search of moral and intellectual improvement? Is it not obvious that the best portion of the colored class are the very ones to prize such an opportunity for instruction? Grant that a large proportion of these unfortunate people are vicious—is it not our duty, and of course our wisest policy, to try to make them otherwise? And what will so effectually elevate their character and condition, as knowledge? I beseech you, my countrymen, think of these things wisely, and in season.

As for intermarriages, if there be such a repugnance between the two races, founded in the laws of nature, methinks there is small reason to dread their frequency.

The breaking down of distinctions in society, by means of extended information, is an objection which appropriately belongs to the Emperor of Austria, or the Sultan of Egypt.

I do not know how the affair at Canterbury is generally considered: but I have heard individuals of all parties and all opinions speak of it—and never without merriment or indignation. Fifty years hence, the black laws of Connecticut will be a greater source of amusement to the antiquarian, than her famous blue laws.

A similar, though less violent opposition arose in consequence of the attempt to establish a college for colored people at New-Haven. A young colored man, who tried to obtain education at the Wesleyan college in Middletown, was obliged to relinquish the attempt on account of the persecution of his fellow students. Some collegians from the South objected to a colored associate in their recitations; and those from New-England promptly and zealously joined in the hue and cry. A small but firm party were in favor of giving the colored man a chance to pursue his studies without insult or interruption; and I am told that this manly and disinterested band were all Southerners. As for those individuals, who exerted their influence to exclude an unoffending fellow-citizen from privileges which ought to be equally open to all, it is to be hoped that age will make them wiser—and that they will learn, before they die, to be ashamed of a step attended with more important results than usually belong to youthful follies.

It happens that these experiments have all been made in Connecticut; but it is no more than justice to that State to remark that a similar spirit would probably have been manifested in Massachusetts, under like circumstances. At our debating clubs and other places of public discussion, the demon of prejudice girds himself for the battle, the moment negro colleges and high schools are alluded to. Alas, while we carry on our lips that religion which teaches us to “love our neighbors as ourselves,” how little do we cherish its blessed influence within our hearts! How much republicanism we have to speak of, and how little do we practise!

Let us seriously consider what injury a negro college could possibly do us. It is certainly a fair presumption that the scholars would be from the better portion of the colored population; and it is an equally fair presumption that knowledge would improve their characters. There are already many hundreds of colored people in the city of Boston. In the street they generally appear neat and respectable; and in our houses they do not “come between the wind and our nobility.” Would the addition of one or two hundred more even be perceived? As for giving offence to the Southerners by allowing such establishments—they have no right to interfere with our internal concerns, any more than we have with theirs. Why should they not give up slavery to please us, by the same rule that we must refrain from educating the negroes to please them? If they are at liberty to do wrong, we certainly ought to be at liberty to do right. They may talk and publish as much about us as they please; and we ask for no other influence over them.

It is a fact not generally known that the brave Kosciusko left a fund for the establishment of a negro college in the United States. Little did he think he had been fighting for a people, who would not grant one rood of their vast territory for the benevolent purpose!

According to present appearances, a college for colored persons will be established in Canada; and thus by means of our foolish and wicked pride, the credit of this philanthropic enterprise will be transferred to our mother country.

The preceding chapters show that it has been no uncommon thing for colored men to be educated at English, German, Portuguese, and Spanish Universities.

In Boston there is an Infant School, three Primary Schools, and a Grammar School. The two last are, I believe, supported by the public; and this fact is highly creditable.

I was much pleased with the late resolution awarding Franklin medals to the colored pupils of the grammar school; and I was still more pleased with the laudable project, originated by Josiah Holbrook, Esq., for the establishment of a colored Lyceum. Surely a better spirit is beginning to work in this cause; and when once begun, the good sense and good feeling of the community will bid it go on and prosper. How much this spirit will have to contend with is illustrated by the following fact. When President Jackson entered this city, the white children of all the schools were sent out in uniform, to do him honor. A member of the Committee proposed that the pupils of the African schools should be invited likewise; but he was the only one who voted for it. He then proposed that the yeas and nays should be recorded; upon which, most of the gentlemen walked off, to prevent the question from being taken. Perhaps they felt an awkward consciousness of the incongeniality of such proceedings with our republican institutions. By order of the Committee the vacation of the African schools did not commence until the day after the procession of the white pupils; and a note to the instructer intimated that the pupils were not expected to appear on the Common. The reason given was because “their numbers were so few;” but in private conversation, fears were expressed lest their sable faces should give offence to our slaveholding President. In all probability the sight of the colored children would have been agreeable to General Jackson, and seemed more like home, than any thing he witnessed.

In the theatre, it is not possible for respectable colored people to obtain a decent seat. They must either be excluded, or herd with the vicious.

A fierce excitement prevailed, not long since, because a colored man had bought a pew in one of our churches. I heard a very kind-hearted and zealous democrat declare his opinion that “the fellow ought to be turned out by constables, if he dared to occupy the pew he had purchased.” Even at the communion-table, the mockery of human pride is mingled with the worship of Jehovah. Again and again have I seen a solitary negro come up to the altar meekly and timidly, after all the white communicants had retired. One Episcopal clergyman of this city, forms an honorable exception to this remark. When there is room at the altar, Mr. —— often makes a signal to the colored members of his church to kneel beside their white brethren; and once, when two white infants and one colored one were to be baptized, and the parents of the latter bashfully lingered far behind the others, he silently rebuked the unchristian spirit of pride, by first administering the holy ordinance to the little dark-skinned child of God.

An instance of prejudice lately occurred, which I should find it hard to believe, did I not positively know it to be a fact. A gallery pew was purchased in one of our churches for two hundred dollars. A few Sabbaths after, an address was delivered at that church, in favor of the Africans. Some colored people, who very naturally wished to hear the discourse, went into the gallery; probably because they thought they should be deemed less intrusive there than elsewhere. The man who had recently bought a pew, found it occupied by colored people, and indignantly retired with his family. The next day, he purchased a pew in another meeting-house, protesting that nothing would tempt him again to make use of seats, that had been occupied by negroes.

A well known country representative, who makes a very loud noise about his democracy, once attended the Catholic church. A pious negro requested him to take off his hat, while he stood in the presence of the Virgin Mary. The white man rudely shoved him aside, saying, “You son of an Ethiopian, do you dare to speak to me!” I more than once heard the hero repeat this story; and he seemed to take peculiar satisfaction in telling it. Had he been less ignorant, he would not have chosen “son of an Ethiopian” as an ignoble epithet; to have called the African his own equal would have been abundantly more sarcastic. The same republican dismissed a strong, industrious colored man, who had been employed on the farm during his absence. “I am too great a democrat,” quoth he, “to have any body in my house, who don’t sit at my table; and I’ll be hanged, if I ever eat with the son of an Ethiopian.”

Men whose education leaves them less excuse for such illiberality, are yet vulgar enough to join in this ridiculous prejudice. The colored woman, whose daughter has been mentioned as excluded from a private school, was once smuggled into a stage, upon the supposition that she was a white woman, with a sallow complexion. Her manners were modest and prepossessing, and the gentlemen were very polite to her. But when she stopped at her own door, and was handed out by her curly-headed husband, they were at once surprised and angry to find they had been riding with a mulatto—and had, in their ignorance, been really civil to her!

A worthy colored woman, belonging to an adjoining town, wished to come into Boston to attend upon a son, who was ill. She had a trunk with her, and was too feeble to walk. She begged permission to ride in the stage. But the passengers with noble indignation, declared they would get out, if she were allowed to get in. After much entreaty, the driver suffered her to sit by him upon the box. When he entered the city, his comrades began to point and sneer. Not having sufficient moral courage to endure this, he left the poor woman, with her trunk, in the middle of the street, far from the place of her destination; telling her, with an oath, that he would not carry her a step further.

A friend of mine lately wished to have a colored girl admitted into the stage with her, to take care of her babe. The girl was very lightly tinged with the sable hue, had handsome Indian features, and very pleasing manners. It was, however, evident that she was not white; and therefore the passengers objected to her company. This of course, produced a good deal of inconvenience on one side, and mortification on the other. My friend repeated the circumstance to a lady, who, as the daughter and wife of a clergyman, might be supposed to have imbibed some liberality. The lady seemed to think the experiment was very preposterous; but when my friend alluded to the mixed parentage of the girl, she exclaimed, with generous enthusiasm, “Oh, that alters the case, Indians certainly have their rights.”

Every year a colored gentleman and scholar is becoming less and less of a rarity—thanks to the existence of the Haytian Republic, and the increasing liberality of the world! Yet if a person of refinement from Hayti, Brazil, or other countries, which we deem less enlightened than our own, should visit us, the very boys of this republic would dog his footsteps with the vulgar outcry of “Nigger! Nigger!” I have known this to be done, from no other provocation than the sight of a colored man with the dress and deportment of a gentleman. Were it not that republicanism, like Christianity, is often perverted from its true spirit by the bad passions of mankind, such things as these would make every honest mind disgusted with the very name of republics.

I am acquainted with a gentleman from Brazil who is shrewd, enterprising, and respectable in character and manners; yet he has experienced almost every species of indignity on account of his color. Not long since, it became necessary for him to visit the southern shores of Massachusetts, to settle certain accounts connected with his business. His wife was in a feeble state of health, and the physicians had recommended a voyage. For this reason, he took passage for her with himself in the steam-boat; and the captain, as it appears, made no objection to a colored gentleman’s money. After remaining on deck some time, Mrs. —— attempted to pass into the cabin; but the captain prevented her; saying, “You must go down forward.” The Brazilian urged that he had paid the customary price, and therefore his wife and infant had a right to a place in the ladies’ cabin. The captain answered, “Your wife a’n’t a lady; she is a nigger.” The forward cabin was occupied by sailors; was entirely without accommodations for women, and admitted the sea-water, so that a person could not sit in it comfortably without keeping the feet raised in a chair. The husband stated that his wife’s health would not admit of such exposure; to which the captain still replied, “I don’t allow any niggers in my cabin.” With natural and honest indignation, the Brazilian exclaimed, “You Americans talk about the Poles! You are a great deal more Russian than the Russians.” The affair was concluded by placing the colored gentleman and his invalid wife on the shore, and leaving them to provide for themselves as they could. Had the cabin been full, there would have been some excuse; but it was occupied only by two sailors’ wives. The same individual sent for a relative in a distant town on account of illness in his family. After staying several weeks, it became necessary for her to return; and he procured a seat for her in the stage. The same ridiculous scene occurred; the passengers were afraid of losing their dignity by riding with a neat respectable person, whose face was darker than their own. No public vehicle could be obtained, by which a colored citizen could be conveyed to her home; it therefore became absolutely necessary for the gentleman to leave his business and hire a chaise at great expense. Such proceedings are really inexcusable. No authority can be found for them in religion, reason, or the laws.

The Bible informs us that “a man of Ethiopia, a eunuch of great authority under Candace, Queen of the Ethiopians, who had charge of all her treasure, came to Jerusalem to worship.” Returning in his chariot, he read Esaias, the Prophet; and at his request Philip went up into the chariot and sat with him, explaining the Scriptures. Where should we now find an apostle, who would ride in the same chariot with an Ethiopian!

[Pg 206] Will any candid person tell me why respectable colored people should not be allowed to make use of public conveyances, open to all who are able and willing to pay for the privilege? Those who enter a vessel, or a stage-coach, cannot expect to select their companions. If they can afford to take a carriage or boat for themselves, then, and then only, they have a right to be exclusive. I was lately talking with a young gentleman on this subject, who professed to have no prejudice against colored people, except so far as they were ignorant and vulgar; but still he could not tolerate the idea of allowing them to enter stages and steam-boats. “Yet, you allow the same privilege to vulgar and ignorant white men, without a murmur,” I replied; “Pray give a good republican reason why a respectable colored citizen should be less favored.” For want of a better argument, he said—(pardon me, fastidious reader)—he implied that the presence of colored persons was less agreeable than Otto of Rose, or Eau de Cologne; and this distinction, he urged was made by God himself. I answered, “Whoever takes his chance in a public vehicle, is liable to meet with uncleanly white passengers, whose breath may be redolent with the fumes of American cigars, or American gin. Neither of these articles have a fragrance peculiarly agreeable to nerves of delicate organization. Allowing your argument double the weight it deserves, it is utter nonsense to pretend that the inconvenience in the case I have supposed is not infinitely greater. But what is more to the point, do you dine in a fashionable hotel, do you sail in a fashionable steam-boat, do you sup at a fashionable house, without having negro servants behind your chair. Would they be any more disagreeable as passengers seated in the corner of a stage, or a steam-boat, than as waiters in such immediate attendance upon your person?”

Stage-drivers are very much perplexed when they attempt to vindicate the present tyrannical customs; and they usually give up the point, by saying they themselves have no prejudice against colored people—they are merely afraid of the public. But stage-drivers should remember that in a popular government, they, in common with every other citizen, form a part and portion of the dreaded public.

The gold was never coined for which I would barter my individual freedom of acting and thinking upon any subject, or knowingly interfere with the rights of the meanest human being. The only true courage is that which impels us to do right without regard to consequences. To fear a populace is as servile as to fear an emperor. The only salutary restraint is the fear of doing wrong.

Our representatives to Congress have repeatedly rode in a stage with colored servants at the request of their masters. Whether this is because New-Englanders are willing to do out of courtesy to a Southern gentleman, what they object to doing from justice to a colored citizen,—or whether those representatives, being educated men, were more than usually divested of this absurd prejudice,—I will not pretend to say.

The state of public feeling not only makes it difficult for the Africans to obtain information, but it prevents them from making profitable use of what knowledge they have. A colored man, however intelligent, is not allowed to pursue any business more lucrative than that of a barber, a shoe-black, or a waiter. These, and all other employments, are truly respectable, whenever the duties connected with them are faithfully performed; but it is unjust that a man should, on account of his complexion, be prevented from performing more elevated uses in society. Every citizen ought to have a fair chance to try his fortune in any line of business, which he thinks he has ability to transact. Why should not colored men be employed in the manufactories of various kinds? If their ignorance is an objection, let them be enlightened, as speedily as possible. If their moral character is not sufficiently pure, remove the pressure of public scorn, and thus supply them with motives for being respectable. All this can be done. It merely requires an earnest wish to overcome a prejudice, which has “grown with our growth and strengthened with our strength,” but which is in fact opposed to the spirit of our religion, and contrary to the instinctive good feelings of our nature. When examined by the clear light of reason, it disappears. Prejudices of all kinds have their strongest holds in the minds of the vulgar and the ignorant. In a community so enlightened as our own, they must gradually melt away under the influence of public discussion. There is no want of kind feelings and liberal sentiments in the American people; the simple fact is, they have not thought upon this subject. An active and enterprising community are not apt to concern themselves about laws and customs, which do not obviously interfere with their interests or convenience; and various political and prudential motives have combined to fetter free inquiry in this direction. Thus we have gone on, year after year, thoughtlessly sanctioning, by our silence and indifference, evils which our hearts and consciences are far enough from approving.

It has been shown that no other people on earth indulge so strong a prejudice with regard to color, as we do. It is urged that negroes are civilly treated in England, because their numbers are so few. I could never discover any great force in this argument. Colored people are certainly not sufficiently rare in that country to be regarded as a great show, like a giraffe, or a Sandwich Island king; and on the other hand, it would seem natural that those who were more accustomed to the sight of dark faces would find their aversion diminished, rather than increased.

The absence of prejudice in the Portuguese and Spanish settlements is accounted for, by saying that the white people are very little superior to the negroes in knowledge and refinement. But Doctor Walsh’s book certainly gives us no reason to think meanly of the Brazilians; and it has been my good fortune to be acquainted with many highly intelligent South Americans, who were divested of this prejudice, and much surprised at its existence here.

If the South Americans are really in such a low state as the argument implies, it is a still greater disgrace to us to be outdone in liberality and consistent republicanism by men so much less enlightened than ourselves.

Pride will doubtless hold out with strength and adroitness against the besiegers of its fortress; but it is an obvious truth that the condition of the world is rapidly improving, and that our laws and customs must change with it.

Neither ancient nor modern history furnishes a page more glorious than the last twenty years in England; for at every step, free principles, after a long and arduous struggle, have conquered selfishness and tyranny. Almost all great evils are resisted by individuals who directly suffer injustice or inconvenience from them; but it is a peculiar beauty of the abolition cause that its defenders enter the lists against wealth, and power, and talent, not to defend their own rights, but to protect weak and injured neighbors, who are not allowed to speak for themselves.

Those who become interested in a cause laboring so heavily under the pressure of present unpopularity, must expect to be assailed by every form of bitterness and sophistry. At times, discouraged and heart-sick, they will perhaps begin to doubt whether there are in reality any unalterable principles of right and wrong. But let them cast aside the fear of man, and keep their minds fixed on a few of the simple, unchangeable laws of God, and they will certainly receive strength to contend with the adversary.

Paragraphs in the Southern papers already begin to imply that the United States will not look tamely on, while England emancipates her slaves; and they inform us that the inspection of the naval stations has become a subject of great importance since the recent measures of the British Parliament. A republic declaring war with a monarchy, because she gave freedom to her slaves, would indeed form a beautiful moral picture for the admiration of the world!

Mr. Garrison was the first person who dared to edit a newspaper, in which slavery was spoken of as altogether wicked and inexcusable. For this crime the Legislature of Georgia have offered five thousand dollars to any one who will “arrest and prosecute him to conviction under the laws of that State.” An association of gentlemen in South Carolina have likewise offered a large reward for the same object. It is, to say the least, a very remarkable step for one State in this Union to promulgate such a law concerning a citizen of another State, merely for publishing his opinions boldly. The disciples of Fanny Wright promulgate the most zealous and virulent attacks upon Christianity, without any hindrance from the civil authorities; and this is done upon the truly rational ground that individual freedom of opinion ought to be respected—that what is false cannot stand, and what is true cannot be overthrown. We leave Christianity to take care of itself; but slavery is a “delicate subject,”—and whoever attacks that must be punished. Mr. Garrison is a disinterested, intelligent, and remarkably pure-minded man, whose only fault is that he cannot be moderate on a subject which it is exceedingly difficult for an honest mind to examine with calmness. Many who highly respect his character and motives, regret his tendency to use wholesale and unqualified expressions; but it is something to have the truth told, even if it be not in the mildest way. Where an evil is powerfully supported by the self-interest and prejudice of the community, none but an ardent individual will venture to meddle with it. Luther was deemed indiscreet even by those who liked him best; yet a more prudent man would never have given an impetus sufficiently powerful to heave the great mass of corruption under which the church was buried. Mr. Garrison has certainly the merit of having first called public attention to a neglected and very important subject. believe whoever fairly and dispassionately examines the question, will be more than disposed to forgive the occasional faults of an ardent temperament, in consideration of the difficulty of the undertaking, and the violence with which it has been opposed.

This remark is not intended to indicate want of respect for the early exertions of the Friends, in their numerous manumission societies; or for the efforts of that staunch, fearless, self-sacrificing friend of freedom—Benjamin Lundy; but Mr. Garrison was the first that boldly attacked slavery as a sin, and Colonization as its twin sister.

The palliator of slavery assures the abolitionists that their benevolence is perfectly quixotic—that the negroes are happy and contented, and have no desire to change their lot. An answer to this may, as I have already said, be found in the Judicial Reports of slaveholding States, in the vigilance of their laws, in advertisements for runaway slaves, and in the details of their own newspapers. The West India planters make the same protestations concerning the happiness of their slaves; yet the cruelties proved by undoubted and unanswerable testimony are enough to sicken the heart. It is said that slavery is a great deal worse in the West Indies than in the United States; but I believe precisely the reverse of this proposition has been true within late years; for the English government have been earnestly trying to atone for their guilt, by the introduction of laws expressly framed to guard the weak and defenceless. A gentleman who has been a great deal among the planters of both countries, and who is by no means favorable to anti-slavery, gives it as his decided opinion that the slaves are better off in the West Indies, than they are in the United States. It is true we hear a great deal more about West Indian cruelty than we do about our own. English books and periodicals are continually full of the subject; and even in the colonies, newspapers openly denounce the hateful system, and take every opportunity to prove the amount of wretchedness it produces. In this country, we have not, until very recently, dared to publish any thing upon the subject. Our books, our reviews, our newspapers, our almanacs, have all been silent, or exerted their influence on the wrong side. The negro’s crimes are repeated, but his sufferings are never told. Even in our geographies it is taught that the colored race must always be degraded. Now and then anecdotes of cruelties committed in the slaveholding States are told by individuals who witnessed them; but they are almost always afraid to give their names to the public, because the Southerners will call them “a disgrace to the soil,” and the Northerners will echo the sentiment. The promptitude and earnestness with which New-England has aided the slaveholders in repressing all discussions which they were desirous to avoid, has called forth many expressions of gratitude in their public speeches, and private conversation; and truly we have well earned Randolph’s favorite appellation, “the white slaves of the North,” by our tameness and servility with regard to a subject where good feeling and good principle alike demand a firm and independent spirit.

We are told that the Southerners will of themselves do away slavery, and they alone understand how to do it. But it is an obvious fact that all their measures have tended to perpetuate the system; and even if we have the fullest faith that they mean to do their duty, the belief by no means absolves us from doing ours. The evil is gigantic; and its removal requires every heart and head in the community.

It is said that our sympathies ought to be given to the masters, who are abundantly more to be pitied than the slaves. If this be the case, the planters are singularly disinterested not to change places with their bondmen. Our sympathies have been given to the masters—and to those masters who seemed most desirous to remain for ever in their pitiable condition. There are hearts at the South sincerely desirous of doing right in this cause; but their generous impulses are checked by the laws of their respective States, and the strong disapprobation of their neighbors. I know a lady in Georgia who would, I believe, make any personal sacrifice to instruct her slaves, and give them freedom; but if she were found guilty of teaching the alphabet, or manumitting her slaves, fines and imprisonment would be the consequence; if she sold them, they would be likely to fall into hands less merciful than her own. Of such slave-owners we cannot speak with too much respect and tenderness. They are comparatively few in number, and stand in a most perplexing situation; it is a duty to give all our sympathy to them. It is mere mockery to say, what is so often said, that the Southerners, as a body, really wish to abolish slavery. If they wished it, they certainly would make the attempt. When the majority heartily desire a change, it is effected, be the difficulties what they may. The Americans are peculiarly responsible for the example they give; for in no other country does the unchecked voice of the people constitute the whole of government.

We must not be induced to excuse slavery by the plausible argument that England introduced it among us. The wickedness of beginning such a work unquestionably belongs to her; the sin of continuing it is certainly our own. It is true that Virginia, while a province, did petition the British government to check the introduction of slaves into the colonies; and their refusal to do so was afterward enumerated among the public reasons for separating from the mother country: but it is equally true that when we became independent, the Southern States stipulated that the slave-trade should not be abolished by law until 1808.

The strongest and best reason that can be given for our supineness on the subject of slavery, is the fear of dissolving the Union. The Constitution of the United States demands our highest reverence. Those who approve, and those who disapprove of particular portions, are equally bound to yield implicit obedience to its authority. But we must not forget that the Constitution provides for any change that may be required for the general good. The great machine is constructed with a safety-valve, by which any rapidly increasing evil may be expelled whenever the people desire it.

If the Southern politicians are determined to make a Siamese question of this also—if they insist that the Union shall not exist without slavery—it can only be said that they join two things, which have no affinity with each other, and which cannot permanently exist together. They chain the living and vigorous to the diseased and dying; and the former will assuredly perish in the infected neighborhood.

The universal introduction of free labor is the surest way to consolidate the Union, and enable us to live together in harmony and peace. If a history is ever written entitled “The Decay and Dissolution of the North American Republic,” its author will distinctly trace our downfall to the existence of slavery among us.

There is hardly any thing bad, in politics or religion, that has not been sanctioned or tolerated by a suffering community, because certain powerful individuals were able to identify the evil with some other principle long consecrated to the hearts and consciences of men.

Under all circumstances, there is but one honest course; and that is to do right, and trust the consequences to Divine Providence. “Duties are ours; events are God’s.” Policy, with all her cunning, can devise no rule so safe, salutary, and effective, as this simple maxim.

We cannot too cautiously examine arguments and excuses brought forward by those whose interest or convenience is connected with keeping their fellow-creatures in a state of ignorance and brutality; and such we shall find in abundance, at the North as well as the South. I have heard the abolition of slavery condemned on the ground that New-England vessels would not be employed to export the produce of the South, if they had free laborers of their own. This objection is so utterly bad in its spirit, that it hardly deserves an answer. Assuredly it is a righteous plan to retard the progress of liberal principles, and “keep human nature for ever in the stocks,” that some individuals may make a few hundred dollars more per annum! Besides the experience of the world abundantly proves that all such forced expedients are unwise. The increased prosperity of one country, or of one section of a country, always contributes, in some form or other, to the prosperity of other states. To “love our neighbor as ourselves,” is, after all, the shrewdest way of doing business.

In England, the abolition of the traffic was long and stoutly resisted, in the same spirit, and by the same arguments, that characterize the defence of the system here; but it would now be difficult to find a man so reckless, that he would not be ashamed of being called a slave-dealer. Public opinion has nearly conquered one evil, and if rightly directed, it will ultimately subdue the other.

Is it asked what can be done? I answer, much, very much, can be effected, if each individual will try to deserve the commendation bestowed by our Saviour on the woman of old—”She hath done what she could.”