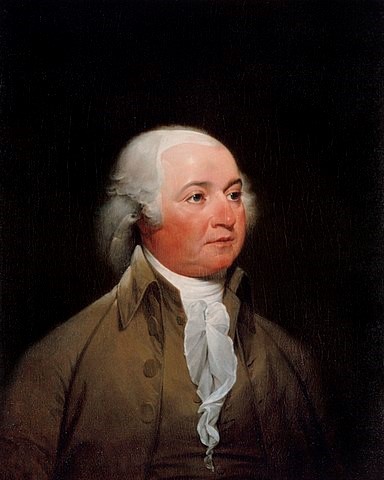

John and Abigail Adams

Letters

Introduction

The letters exchanged by John and Abigail Adams were written between 1774 and 1776, during the heart of the Revolutionary War period. At times, the Adamses write of very personal experiences: their children, domestic life, illnesses, and of missing one another. At other times, they write about war and the political landscape: what is being printed in the papers and what is being debated by the Continental Congress. This combination of both intimate conversations about the home and discussions about governmental processes reminds us not only of the humanity of these “founding” figures, but also that the political matters they discussed were also very personal. This is, perhaps, one reason why Abigail reminded her husband to “Remember the Ladies” as he worked with other men to establish the guiding principles of this new nation. As you read their letters, consider how they negotiate their roles in this changing environment, and how their exchanges offer another dimension to the larger public conversation about what counts as American.

Discussion Questions:

- How do the John and Abigail Adams letters convey their own ideas about what counts as American? What values or qualities do they emphasize? What strategies do they use to convey these ideas?

- Why might these letters be important in the study of American literature? Why or how might they still be relevant today?

- Although John and Abigail Adams are writing directly to one another, their letters reveal that they are also in conversation (even if indirectly) with other prominent figures during this period. How do their letters, or the ideas in those letters, extend the ideas offered by writers like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, or Phyllis Wheatley?

13. Abigail Adams.

Braintree, 19 August, 1774.

The great distance between us makes the time appear very long to me. It seems already a month since you left me. The great anxiety I feel for my country, for you, and for our family renders the day tedious and the night unpleasant. The rocks and quicksands appear upon every side. What course you can or will take is all wrapped in the bosom of futurity. Uncertainty and expectation leave the mind great scope. Did ever any kingdom or state regain its liberty, when once it was invaded, without bloodshed? I cannot think of it without horror. Yet we are told that all the misfortunes of Sparta were occasioned by their too great solicitude for present tranquillity, and, from an excessive love of peace, they neglected the means of making it sure and lasting. They ought to have reflected, says Polybius, that, “as there is nothing more desirable or advantageous than peace, when founded in justice and honor, so there is nothing more shameful, and at the same time more pernicious, when attained by bad measures and purchased at the price of liberty.” I have received a most charming letter from our friend Mrs. Warren.[36] She desires me to tell you that her best wishes attend you through your journey, both as a friend and a patriot,—hopes you will have no uncommon difficulties to surmount, or hostile movements to impede you, but, if the Locrians should interrupt you, she hopes that you will beware, that no future annals may say you chose an ambitious Philip for your leader, who subverted the noble order of the American Amphictyons, and built up a monarchy on the ruins of the happy institution.

I have taken a very great fondness for reading Rollin’s Ancient History since you left me. I am determined to go through with it, if possible, in these my days of solitude.

I find great pleasure and entertainment from it, and I have persuaded Johnny to read me a page or two every day, and hope he will, from his desire to oblige me, entertain a fondness for it. We have had a charming rain, which lasted twelve hours and has greatly revived the dying fruits of the earth.

I want much to hear from you. I long impatiently to have you upon the stage of action. The first of September, or the month of September, perhaps, may be of as much importance to Great Britain as the Ides of March were to Cæsar. I wish you every public as well as private blessing, and that wisdom which is profitable both for instruction and edification, to conduct you in this difficult day. The little flock remember papa, and kindly wish to see him; so does your most affectionate

Abigail Adams.

FOOTNOTES:

[36] Mercy Warren, the sister of James Otis, and the wife of James Warren, of Plymouth; the author of the little satire called The Group, and of a History of the Revolutionary War. Few of her sex took a more active interest in the struggle of the Revolution.

14. John Adams.

Princeton, New Jersey, 28 August, 1774.

I received your kind letter at New York, and it is not easy for you to imagine the pleasure it has given me. I have not found a single opportunity to write since I left Boston, excepting by the post, and I don’t choose to write by that conveyance, for fear of foul play. But as we are now within forty-two miles of Philadelphia, I hope there to find some private hand by which I can convey this.

The particulars of our journey I must reserve, to be communicated after my return. It would take a volume to describe the whole. It has been upon the whole an agreeable jaunt. We have had opportunities to see the world and to form acquaintances with the most eminent and famous men in the several colonies we have passed through. We have been treated with unbounded civility, complaisance, and respect. We yesterday visited Nassau Hall College, and were politely treated by the scholars, tutors, professors, and president, whom we are this day to hear preach. To-morrow we reach the theatre of action. God Almighty grant us wisdom and virtue sufficient for the high trust that is devolved upon us. The spirit of the people, wherever we have been, seems to be very favorable. They universally consider our cause as their own, and express the firmest resolution to abide by the determination of the Congress.

I am anxious for our perplexed, distressed province; hope they will be directed into the right path. Let me entreat you, my dear, to make yourself as easy and quiet as possible. Resignation to the will of Heaven is our only resource in such dangerous times. Prudence and caution should be our guides. I have the strongest hopes that we shall yet see a clearer sky and better times.

Remember my tender love to little Abby; tell her she must write me a letter and inclose it in the next you send. I am charmed with your amusement with our little Johnny. Tell him I am glad to hear he is so good a boy as to read to his mamma for her entertainment, and to keep himself out of the company of rude children. Tell him I hope to hear a good account of his accidence and nomenclature when I return. Remember me to all inquiring friends, particularly to uncle Quincy,[37] your papa and family, and Dr. Tufts and family. Mr. Thaxter,[38] I hope, is a good companion in your solitude. Tell him, if he devotes his soul and body to his books, I hope, notwithstanding the darkness of these days, he will not find them unprofitable sacrifices in future. I have received three very obliging letters from Tudor, Trumbull, and Hill.[39] They have cheered us in our wanderings and done us much service.

Your account of the rain refreshed me. I hope our husbandry is prudently and industriously managed. Frugality must be our support. Our expenses in this journey will be very great. Our only [recompense will[40] be the consolatory reflection that we toil, spend our time, and [encounter] dangers for the public good—happy indeed if we do any good.

The education of our children is never out of my mind. Train them to virtue. Habituate them to industry, activity, and spirit. Make them consider every vice as shameful and unmanly. Fire them with ambition to be useful. Make them disdain to be destitute of any useful or ornamental knowledge or accomplishment. Fix their ambition upon great and solid objects, and their contempt upon little, frivolous, and useless ones. It is time, my dear, for you to begin to teach them French. Every decency, grace, and honesty should be inculcated upon them.

I have kept a few minutes by way of journal, which shall be your entertainment when I come home; but we have had so many persons and so various characters to converse with, and so many objects to view, that I have not been able to be so particular as I could wish. I am, with the tenderest affection and concern,

Your wandering John Adams.

FOOTNOTES:

[37] Norton Quincy, a graduate of Harvard College in 1736, and the only brother of Mrs. Adams’s mother. Sympathizing with the patriotic movement he was placed on the first committee of safety organized by the Provincial Assembly. But no inducements could prevail to draw him from his seclusion at Mount Wollaston, where he lived, and died in 1801.

[38] John Thaxter, Jr., who with the three others here named and two more were clerks with Mr. Adams at the breaking out of the Revolution. Mr. Thaxter afterwards acted as private secretary to Mr. Adams during his second residence in Europe, down to the date of the treaty of peace, of which he was made the bearer to the United States.

[39] William Tudor, John Trumbull, and Jeremiah Hill. Some of these letters remain, and are not without interest as contemporaneous accounts of Revolutionary events.

[40] The words in brackets supplied, as the manuscript is defective.

15. Abigail Adams.

Braintree, 2 September, 1774.

I am very impatient to receive a letter from you. You indulged me so much in that way in your last absence, that I now think I have a right to hear as often from you as you have leisure and opportunity to write. I hear that Mr. Adams[41] wrote to his son, and the Speakerto his lady; but perhaps you did not know of the opportunity. I suppose you have before this time received two letters from me, and will write me by the same conveyance. I judge you reached Philadelphia last Saturday night. I cannot but felicitate you upon your absence a little while from this scene of perturbation, anxiety, and distress. I own I feel not a little agitated with the accounts I have this day received from town; great commotions have arisen in consequence of a discovery of a traitorous plot of Colonel Brattle’s,—his advice to Gage to break every commissioned officer and to seize the province’s and town’s stock of gunpowder.[42] This has so enraged and exasperated the people that there is great apprehension of an immediate rupture. They have been all in flames ever since the new-fangled counselors have taken their oaths. The importance, of which they consider the meeting of the Congress, and the result thereof to the community withholds the arm of vengeance already lifted, which would most certainly fall with accumulated wrath upon Brattle, were it possible to come at him; but no sooner did he discover that his treachery had taken air than he fled, not only to Boston, but into the camp, for safety. You will, by Mr. Tudor, no doubt have a much more accurate account than I am able to give you; but one thing I can inform you of which perhaps you may not have heard, namely, Mr. Vinton, our sheriff, it seems, received one of those twenty warrants[43] which were issued by Messrs. Goldthwait and Price, which has cost them such bitter repentance and humble acknowledgments, and which has revealed the great secret of their attachment to the liberties of their country, and their veneration and regard for the good-will of their countrymen. See their address to Hutchinson and Gage. This warrant, which was for Stoughtonham,[44] Vinton carried and delivered to a constable there; but before he had got six miles he was overtaken by sixty men on horseback, who surrounded him and told him unless he returned with them and demanded back that warrant and committed it to the flames before their faces, he must take the consequences of a refusal; and he, not thinking it best to endure their vengeance, returned with them, made his demand of the warrant, and consumed it, upon which they dispersed and left him to his own reflections. Since the news of the Quebec bill arrived, all the Church people here have hung their heads and will not converse upon politics, though ever so much provoked by the opposite party. Before that, parties ran very high, and very hard words and threats of blows upon both sides were given out. They have had their town-meeting here, which was full as usual, chose their committee for the county meeting, and did business without once regarding or fearing for the consequences.[45]

I should be glad to know how you found the people as you travelled from town to town. I hear you met with great hospitality and kindness in Connecticut. Pray let me know how your health is, and whether you have not had exceeding hot weather. The drought has been very severe. My poor cows will certainly prefer a petition to you, setting forth their grievances and informing you that they have been deprived of their ancient privileges, whereby they are become great sufferers, and desiring that they may be restored to them. More especially as their living, by reason of the drought, is all taken from them, and their property which they hold elsewhere is decaying, they humbly pray that you would consider them, lest hunger should break through stone walls.

The tenderest regard evermore awaits you from your most affectionate

Abigail Adams.

FOOTNOTES:

[41] Samuel Adams and Thomas Cushing, both of them delegates.

[42] “Mr. Brattle begs leave to quere whether it would not be best that there should not be one commissioned officer of the militia in the province.” (Brattle to General Gage, 26 August.)

The other rumor is not sustained by this letter, as General Brattle there announces that all the town’s stock of powder had been surrendered, and none was left but the king’s, meaning thereby what belonged to the province. But whether he advised it or not, it is certain that a detachment of the regular troops was sent out of Boston on the 1st of September to secure all the powder left at Charlestown, and to bring it away, which was done.

[43] Writs to summon juries. The administration of justice had been stopped by the impeachment of Chief Justice Oliver, and the refusal of the juries to act under him. The present attempt was intended to deter all others from becoming jurors.

[44] The old name of the town of Sharon.

[45] The most clear and decisive account of the general rising that took place at this time in the province is given in the official letter of General Gage to Lord Dartmouth, of the same date with this letter. Am. Archives for 1774, p. 767.

16. John Adams.

Philadelphia, 8 September, 1774.

When or where this letter will find you I know not. In what scenes of distress and terror I cannot foresee. We have received a confused account from Boston of a dreadful catastrophe. The particulars we have not heard. We are waiting with the utmost anxiety and impatience for further intelligence. The effect of the news we have, both upon the Congress and the inhabitants of this city, was very great. Great indeed! Every gentleman seems to consider the bombardment[46] of Boston as the bombardment of the capital of his own province. Our deliberations are grave and serious indeed.

It is a great affliction to me that I cannot write to you oftener than I do. But there are so many hindrances that I cannot. It would fill volumes to give you an idea of the scenes I behold, and the characters I converse with. We have so much business, so much ceremony, so much company, so many visits to receive and return, that I have not time to write. And the times are such as to make it imprudent to write freely.

We cannot depart from this place until the business of the Congress is completed, and it is the general disposition to proceed slowly. When I shall be at home I can’t say. If there is distress and danger in Boston, pray invite our friends, as many as possible, to take an asylum with you,—Mrs. Cushing and Mrs. Adams, if you can. There is in the Congress a collection of the greatest men upon this continent in point of abilities, virtues, and fortunes. The magnanimity and public spirit which I see here make me blush for the sordid, venal herd which I have seen in my own province. The addressers, and the new councillors[47] are held in universal contempt and abhorrence from one end of the continent to the other.

Be not under any concern for me. There is little danger from anything we shall do at the Congress. There is such a spirit through the colonies, and the members of the Congress are such characters, that no danger can happen to us which will not involve the whole continent in universal desolation; and in that case, who would wish to live? Adieu.

FOOTNOTES:

[46] Dr. Gordon says that the rumors spread of the seizure of the gunpowder, and of General Gage’s measures to fortify himself against surprise, rapidly swelled into a story that the fleet and the army were firing into the town. As a consequence, in less than twenty-four hours a multitude had collected from thirty miles around, of not less than thirty or forty thousand people. Nothing could be more absurd in itself, considering that Boston was the only place Gage could hope to hold as a refuge for the royalists flying from all the other towns, yet the alarm had a very decided effect in hastening the action of the collected delegates at Philadelphia, and in uniting the sentiments of the people in the other colonies.

[47] These were the persons nominated as councillors by mandamus, under the new act for the regulation of the province charter. Most of them were compelled by the people to resign their places, and some were driven from home never to return.

17. John Adams.

Philadelphia, 14 September, 1774.

I have written but once to you since I left you. This is to be imputed to a variety of causes, which I cannot explain for want of time. It would fill volumes to give you an exact idea of the whole tour. My time is totally filled from the moment I get out of bed until I return to it. Visits, ceremonies, company, business, newspapers, pamphlets, etc., etc., etc.

The Congress will, to all present appearance, be well united, and in such measures as, I hope, will give satisfaction to the friends of our country. A Tory here is the most despicable animal in the creation. Spiders, toads, snakes are their only proper emblems. The Massachusetts councillors and addressers are held in curious esteem here, as you will see. The spirit, the firmness, the prudence of our province are vastly applauded, and we are universally acknowledged the saviours and defenders of American liberty. The designs and plans of the Congress must not be communicated until completed, and we shall move with great deliberation.

When I shall come home I know not, but at present I do not expect to take my leave of this city these four weeks.

My compliments, love, service, where they are due. My babes are never out of my mind, nor absent from my heart. Adieu.

18. Abigail Adams.

Braintree, 14 September, 1774.

Five weeks have passed and not one line have I received. I would rather give a dollar for a letter by the post, though the consequence should be that I ate but one meal a day these three weeks to come. Every one I see is inquiring after you, when did I hear. All my intelligence is collected from the newspaper, and I can only reply that I saw by that, you arrived such a day. I know your fondness for writing, and your inclination to let me hear from you by the first safe conveyance, which makes me suspect that some letter or other has miscarried; but I hope, now you have arrived at Philadelphia, you will find means to convey me some intelligence.

We are all well here. I think I enjoy better health than I have done these two years. I have not been to town since I parted with you there. The Governor is making all kinds of warlike preparations, such as mounting cannon upon Beacon Hill, digging intrenchments upon the Neck, placing cannon there, encamping a regiment there, throwing up breast-works, etc. The people are much alarmed, and the selectmen have waited upon him in consequence of it. The County Congress[48] have also sent a committee; all which proceedings you will have a more particular account of than I am able to give you, from the public papers. But as to the movements of this town, perhaps you may not hear them from any other person.

In consequence of the powder being taken from Charlestown, a general alarm spread through many towns and was caught pretty soon here. The report took here on Friday, and on Sunday a soldier was seen lurking about the Common, supposed to be a spy, but most likely a deserter. However, intelligence of it was communicated to the other parishes, and about eight o’clock Sunday evening there passed by here about two hundred men, preceded by a horsecart, and marched down to the powder-house, from whence they took the powder, and carried it into the other parish and there secreted it. I opened the window upon their return. They passed without any noise, not a word among them till they came against this house, when some of them, perceiving me, asked me if I wanted any powder. I replied, No, since it was in so good hands. The reason they gave for taking it was that we had so many Tories here, they dared not trust us with it; they had taken Vinton in their train, and upon their return they stopped between Cleverly’s and Etter’s, and called upon him to deliver two warrants. Upon his producing them, they put it to vote whether they should burn them, and it passed in the affirmative. They then made a circle and burnt them. They then called a vote whether they should huzza, but, it being Sunday evening, it passed in the negative. They called upon Vinton to swear that he would never be instrumental in carrying into execution any of these new acts. They were not satisfied with his answers; however, they let him rest. A few days afterwards, upon his making some foolish speeches, they assembled to the amount of two or three hundred, and swore vengeance upon him unless he took a solemn oath. Accordingly, they chose a committee and sent it with him to Major Miller’s to see that he complied; and they waited his return, which proving satisfactory, they dispersed. This town appears as high as you can well imagine, and, if necessary, would soon be in arms. Not a Tory but hides his head. The church parson thought they were coming after him, and ran up garret; they say another jumped out of his window and hid among the corn, whilst a third crept under his board fence and told his beads.

16 September, 1774.

I dined to-day at Colonel Quincy’s.[49] They were so kind as to send me and Abby and Betsey an invitation to spend the day with them; and, as I had not been to see them since I removed to Braintree, I accepted the invitation. After I got there came Mr. Samuel Quincy’s wife and Mr. Sumner, Mr. Josiah and wife. A little clashing of parties, you may be sure. Mr. Sam’s wife said she thought it high time for her husband to turn about; he had not done half so cleverly since he left her advice; said they both greatly admired the most excellent speech of the Bishop of St. Asaph, which I suppose you have seen. It meets, and most certainly merits, the greatest encomiums.[50]

Upon my return at night, Mr. Thaxter met me at the door with your letter, dated at Princeton, New Jersey. It really gave me such a flow of spirits that I was not composed enough to sleep until one o’clock. You make no mention of one I wrote you previous to that you received by Mr. Breck, and sent by Mr. Cunningham. I am rejoiced to hear you are well. I want to know many more particulars than you write me, and hope soon to hear from you again. I dare not trust myself with the thought how long you may perhaps be absent. I only count the weeks already past, and they amount to five. I am not so lonely as I should have been without my two neighbors;[51] we make a table-full at meal times. All the rest of their time they spend in the office. Never were two persons who gave a family less trouble than they do. It is at last determined that Mr. Rice keep the school here. Indeed, he has kept ever since he has been here, but not with any expectation that he should be continued; but the people, finding no small difference between him and his predecessor, chose he should be continued. I have not sent Johnny.[52] He goes very steadily to Mr. Thaxter, who I believe takes very good care of him; and as they seem to have a liking to each other, I believe it will be best to continue him with him. However, when you return, we can consult what will be best. I am certain that, if he does not get so much good, he gets less harm; and I have always thought it of very great importance that children should, in the early part of life, be unaccustomed to such examples as would tend to corrupt the purity of their words and actions, that they may chill with horror at the sound of an oath, and blush with indignation at an obscene expression. These first principles, which grow with their growth, and strengthen with their strength, neither time nor custom can totally eradicate.

You will perhaps be tired. No. Let it serve by way of relaxation from the more important concerns of the day, and be such an amusement as your little hermitage used to afford you here. You have before you, to express myself in the words of the bishop, the greatest national concerns that ever came before any people; and if the prayers and petitions ascend unto heaven which are daily offered for you, wisdom will flow down as a stream, and righteousness as the mighty waters, and your deliberations will make glad the cities of our God.

I was very sorry I did not know of Mr. Cary’s going; it would have been so good an opportunity to have sent this, as I lament the loss of. You have heard, no doubt, of the people’s preventing the court from sitting in various counties; and last week, in Taunton, Angier urged the court’s opening and calling out the actions, but could not effect it. I saw a letter from Miss Eunice,[53] wherein she gives an account of it, and says there were two thousand men assembled round the court-house, and, by a committee of nine, presented a petition requesting that they would not sit, and with the utmost order waited two hours for their answer, when they dispersed.

You will burn all these letters, lest they should fall from your pocket, and thus expose your most affectionate friend.

FOOTNOTES:

[48] This was the great meeting of delegates from all parts of Suffolk County which passed the resolves commonly known as the Suffolk Resolves.

[49] Josiah Quincy, a graduate of Harvard College in 1728, and the father of the two others here named.

[50] Dr. Jonathan Shipley, Bishop of St. Asaph, had distinguished himself by his opposition to the policy of the Government upon two occasions. The first in a sermon preached in February, 1773, before the society for the Propagation of the Gospel, which received the warm approbation of Lord Chatham. The second by a speech in the House of Lords. It is to the latter that the reference is made.

[51] John Thaxter, already mentioned, and Nathan Rice, who graduated at Harvard College in 1773, and entered immediately as a clerk in Mr. Adams’s office. The latter took a commission in the army, and served with credit through the war. He survived until 1834.

[52] John Quincy Adams, at this time seven years old.

[53] Miss Eunice Paine, a sister of Robert Treat Paine, and for many years an intimate friend of the writer.

19. John Adams.

Philadelphia, 16 September, 1774.

Having a leisure moment, while the Congress is assembling, I gladly embrace it to write you a line.

When the Congress first met, Mr. Cushing made a motion that it should be opened with prayer. It was opposed by Mr. Jay, of New York, and Mr. Rutledge, of South Carolina, because we were so divided in religious sentiments, some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Anabaptists, some Presbyterians, and some Congregationalists, that we could not join in the same act of worship. Mr. Samuel Adams arose and said he was no bigot, and could hear a prayer from a gentleman of piety and virtue, who was at the same time a friend to his country. He was a stranger in Philadelphia, but had heard that Mr. Duché (Dushay they pronounce it) deserved that character, and therefore he moved that Mr. Duché, an Episcopal clergyman, might be desired to read prayers to the Congress, to-morrow morning. The motion was seconded and passed in the affirmative. Mr. Randolph, our president, waited on Mr. Duché, and received for answer that if his health would permit he certainly would. Accordingly, next morning he appeared with his clerk and in his pontificals, and read several prayers in the established form; and then read the Collect for the seventh day of September, which was the thirty-fifth Psalm. You must remember this was the next morning after we heard the horrible rumor of the cannonade of Boston. I never saw a greater effect upon an audience. It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to be read on that morning.

After this, Mr. Duché, unexpected to everybody, struck out into an extemporary prayer, which filled the bosom of every man present. I must confess I never beard a better prayer, or one so well pronounced. Episcopalian as he is, Dr. Cooper himself[54] never prayed with such fervor, such ardor, such earnestness and pathos, and in language so elegant and sublime—for America, for the Congress, for the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and especially the town of Boston. It has had an excellent effect upon everybody here. I must beg you to read that Psalm. If there was any faith in the Sortes Biblicæ, it would be thought providential.

It will amuse your friends to read this letter and the thirty-fifth Psalm to them. Read it to your father and Mr. Wibird. I wonder what our Braintree Churchmen will think of this! Mr. Duché is one of the most ingenious men, and best characters, and greatest orators in the Episcopal order, upon this continent. Yet a zealous friend of Liberty and his country.[55]

I long to see my dear family. God bless, preserve, and prosper it. Adieu.

FOOTNOTES:

[54] Dr. Samuel Cooper, well known as a zealous patriot and pastor of the church in Brattle Square. The edifice, at that time esteemed the finest interior in Boston, and yet much admired, had been completed about a year. It has now gone the way of all old structures in Boston. Mr. Adams had become a proprietor and a worshipper at this church.

[55] He held out tolerably well for two years. But the apparent preponderance of British power on the one side, and his sectarian prejudices against the Independents of New England on the other, finally got the better of him, so far as to dictate the appeal to General Washington, in the gloomiest period of the war, which forever forfeited for him all claim to the commendation above bestowed.

79. Abigail Adams.

27 November, 1775.

Colonel Warren returned last week to Plymouth, so that I shall not hear anything from you until he goes back again, which will not be till the last of this month. He damped my spirits greatly by telling me that the Court[117] had prolonged your stay another month. I was pleasing myself with the thought that you would soon be upon your return. It is in vain to repine. I hope the public will reap what I sacrifice.

I wish I knew what mighty things were fabricating. If a form of government is to be established here, what one will be assumed? Will it be left to our Assemblies to choose one? And will not many men have many minds? And shall we not run into dissensions among ourselves?

I am more and more convinced that man is a dangerous creature; and that power, whether vested in many or a few, is ever grasping, and, like the grave, cries, “Give, give!” The great fish swallow up the small; and he who is most strenuous for the rights of the people, when vested with power, is as eager after the prerogatives of government. You tell me of degrees of perfection to which human nature is capable of arriving, and I believe it, but at the same time lament that our admiration should arise from the scarcity of the instances.

The building up a great empire, which was only hinted at by my correspondent, may now, I suppose, be realized even by the unbelievers. Yet, will not ten thousand difficulties arise in the formation of it? The reins of government have been so long slackened, that I fear the people will not quietly submit to those restraints which are necessary for the peace and security of the community. If we separate from Britain, what code of laws will be established? How shall we be governed so as to retain our liberties? Can any government be free which is not administered by general stated laws? Who shall frame these laws? Who will give them force and energy? It is true, your resolutions, as a body, have hitherto had the force of laws; but will they continue to have?

When I consider these things, and the prejudices of people in favor of ancient customs and regulations, I feel anxious for the fate of our monarchy, or democracy, or whatever is to take place. I soon get lost in a labyrinth of perplexities; but, whatever occurs, may justice and righteousness be the stability of our times, and order arise out of confusion. Great difficulties may be surmounted by patience and perseverance.

I believe I have tired you with politics. As to news, we have not any at all. I shudder at the approach of winter, when I think I am to remain desolate.

I must bid you good night; ‘t is late for me, who am much of an invalid. I was disappointed last week in receiving a packet by the post, and, upon unsealing it, finding only four newspapers. I think you are more cautious than you need be. All letters, I believe, have come safe to hand. I have sixteen from you, and wish I had as many more. Adieu.

Yours.

FOOTNOTES:

[117] The legislative government.

91. Abigail Adams.

Braintree, 31 March, 1776.

I wish you would ever write me a letter half as long as I write you, and tell me, if you may, where your fleet are gone; what sort of defense Virginia can make against our common enemy; whether it is so situated as to make an able defense. Are not the gentry lords, and the common people vassals? Are they not like the uncivilized vassals Britain represents us to be? I hope their riflemen, who have shown themselves very savage and even blood-thirsty, are not a specimen of the generality of the people. I am willing to allow the colony great merit for having produced a Washington; but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for liberty cannot be equally strong in the breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow-creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain, that it is not founded upon that generous and Christian principle of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.

Do not you want to see Boston? I am fearful of the small-pox, or I should have been in before this time. I got Mr. Crane to go to our house and see what state it was in. I find it has been occupied by one of[149] the doctors of a regiment; very dirty, but no other damage has been done to it. The few things which were left in it are all gone. I look upon it as a new acquisition of property—a property which one month ago I did not value at a single shilling, and would with pleasure have seen it in flames.

The town in general is left in a better state than we expected; more owing to a precipitate flight than any regard to the inhabitants; though some individuals discovered a sense of honor and justice, and have left the rent of the houses in which they were, for the owners, and the furniture unhurt, or, if damaged, sufficient to make it good. Others have committed abominable ravages. The mansion-house of your President is safe, and the furniture unhurt; while the house and furniture of the Solicitor General have fallen a prey to their own merciless party. Surely the very fiends feel a reverential awe for virtue and patriotism, whilst they detest the parricide and traitor.

I feel very differently at the approach of spring from what I did a month ago. We knew not then whether we could plant or sow with safety, whether where we had tilled we could reap the fruits of our own industry, whether we could rest in our own cottages or whether we should be driven from the seacoast to seek shelter in the wilderness; but now we feel a temporary peace, and the poor fugitives are returning to their deserted habitations.

Though we felicitate ourselves, we sympathize with those who are trembling lest the lot of Boston should be theirs. But they cannot be in similar circumstances unless pusillanimity and cowardice should take possession of them. They have time and warning given them to see the evil and shun it.

I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the[150] ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute; but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend. Why, then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity? Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your sex; regard us then as beings placed by Providence under your protection, and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

April 5.

I want to hear much oftener from you than I do. March 8th was the last date of any that I have yet had. You inquire of me whether I am making saltpetre. I have not yet attempted it, but after soap-making believe I shall make the experiment. I find as much as I can do to manufacture clothing for my family, which would else be naked. I know of but one person in this part of the town who has made any. That is Mr. Tertius Bass, as he is called, who has got very near a hundred-weight which has been found to be very good. I have heard of some others in the other parishes. Mr. Reed, of Weymouth, has been applied to, to go to Andover to the mills which are now at work, and he has gone.

I have lately seen a small manuscript describing the proportions of the various sorts of powder fit for cannon, small-arms, and pistols. If it would be of any service your way I will get it transcribed and send it to you. Every one of your friends sends regards, and all the little ones. Adieu.

114. John Adams.

3 July, 1776.

Your favor of 17 June, dated at Plymouth, was handed me by yesterday’s post. I was much pleased to find that you had taken a journey to Plymouth, to see your friends, in the long absence of one whom you may wish to see. The excursion will be an amusement, and will serve your health. How happy would it have made me to have taken this journey with you!

I was informed, a day or two before the receipt of your letter, that you was gone to Plymouth, by Mrs. Polly Palmer, who was obliging enough, in your absence, to send me the particulars of the expedition to the lower harbor against the men-of-war. Her narration is executed with a precision and perspicuity, which would have become the pen of an accomplished historian.

I am very glad you had so good an opportunity of seeing one of our little American men-of-war. Many ideas new to you must have presented themselves in such a scene; and you will, in future, better understand the relations of sea engagements.

I rejoice extremely at Dr. Bulfinch’s petition to open a hospital. But I hope the business will be done upon a larger scale. I hope that one hospital will be licensed in every county, if not in every town. I am happy to find you resolved to be with the children in the first class. Mr. Whitney and Mrs. Katy Quincy are cleverly through inoculation in this city.

The information you give me of our friend’s refusing his appointment has given me much pain, grief, and anxiety. I believe I shall be obliged to follow his example. I have not fortune enough to support my family, and, what is of more importance, to support the dignity of that exalted station. It is too high and lifted up for me, who delight in nothing so much as retreat, solitude, silence, and obscurity. In private life, no one has a right to censure me for following my own inclinations in retirement, simplicity, and frugality. In public life, every man has a right to remark as he pleases. At least he thinks so.

Yesterday, the greatest question was decided which ever was debated in America, and a greater, perhaps, never was nor will be decided among men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, and as such they have, and of right ought to have, full power to make war, conclude peace, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which other States may rightfully do.” You will see, in a few days, a Declaration setting forth the causes which have impelled us to this mighty revolution, and the reasons which will justify it in the sight of God and man. A plan of confederation will be taken up in a few days.

When I look back to the year 1761, and recollect the argument concerning writs of assistance in the superior court, which I have hitherto considered as the commencement of this controversy between Great Britain and America, and run through the whole period from that time to this, and recollect the series of political events, the chain of causes and effects, I am surprised at the suddenness as well as greatness of this revolution. Britain has been filled with folly, and America with wisdom; at least, this is my judgment. Time must determine. It is the will of Heaven that the two countries should be sundered forever. It may be the will of Heaven that America shall suffer calamities still more wasting, and distresses yet more dreadful. If this is to be the case, it will have this good effect at least. It will inspire us with many virtues which we have not, and correct many errors, follies, and vices which threaten to disturb, dishonor, and destroy us. The furnace of affliction produces refinement in states as well as individuals. And the new Governments we are assuming in every part will require a purification from our vices, and an augmentation of our virtues, or they will be no blessings. The people will have unbounded power, and the people are extremely addicted to corruption and venality, as well as the great. But I must submit all my hopes and fears to an overruling Providence, in which, unfashionable as the faith may be, I firmly believe.

115. John Adams.

Philadelphia, 3 July, 1776.

Had a Declaration of Independency been made seven months ago, it would have been attended with many great and glorious effects. We might, before this hour, have formed alliances with foreign states. We should have mastered Quebec, and been in possession of Canada. You will perhaps wonder how such a declaration would have influenced our affairs in Canada, but if I could write with freedom, I could easily convince you that it would, and explain to you the manner how. Many gentlemen in high stations, and of great influence, have been duped by the ministerial bubble of Commissioners to treat. And in real, sincere expectation of this event, which they so fondly wished, they have been slow and languid in promoting measures for the reduction of that province. Others there are in the Colonies who really wished that our enterprise in Canada would be defeated, that the Colonies might be brought into danger and distress between two fires, and be thus induced to submit. Others really wished to defeat the expedition to Canada, lest the conquest of it should elevate the minds of the people too much to hearken to those terms of reconciliation which, they believed, would be offered us. These jarring views, wishes, and designs occasioned an opposition to many salutary measures which were proposed for the support of that expedition, and caused obstructions, embarrassments, and studied delays, which have finally lost us the province.

All these causes, however, in conjunction would not have disappointed us, if it had not been for a misfortune which could not be foreseen, and perhaps could not have been prevented; I mean the prevalence of the small-pox among our troops. This fatal pestilence completed our destruction. It is a frown of Providence upon us, which we ought to lay to heart.

But, on the other hand, the delay of this Declaration to this time has many great advantages attending it. The hopes of reconciliation which were fondly entertained by multitudes of honest and well-meaning, though weak and mistaken people, have been gradually, and at last totally extinguished. Time has been given for the whole people maturely to consider the great question of independence, and to ripen their judgment, dissipate their fears, and allure their hopes, by discussing it in newspapers and pamphlets, by debating it in assemblies, conventions, committees of safety and inspection, in town and county meetings, as well as in private conversations, so that the whole people, in every colony of the thirteen, have now adopted it as their own act. This will cement the union, and avoid those heats, and perhaps convulsions, which might have been occasioned by such a Declaration six months ago.

But the day is past. The second[146] day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. [194]It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.

You will think me transported with enthusiasm, but I am not. I am well aware of the toil and blood and treasure that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration and support and defend these States. Yet, through all the gloom, I can see the rays of ravishing light and glory. I can see that the end is more than worth all the means. And that posterity will triumph in that day’s transaction, even although we should rue it, which I trust in God we shall not.

FOOTNOTES:

[146] The practice has been to celebrate the 4th of July, the day upon which the form of the Declaration of Independence was agreed to, rather than the 2d, the day upon which the resolution making that declaration was determined upon by the Congress. A friend of Mr. Adams, who had during his lifetime an opportunity to read the two letters dated on the 3d, was so much struck with them, that he procured the liberty to publish them. But thinking, probably, that a slight alteration would better fit them for the taste of the day, and gain for them a higher character for prophecy, than if printed as they were, he obtained leave to put together only the most remarkable paragraphs, and make one letter out of the two. He then changed the date from the 3d to the 5th, and the word second to fourth, and published it, the public being made aware of these alterations. In this form, and as connected with the anniversary of our National Independence, these letters have ever since enjoyed great popularity. The editor at first entertained some doubt of the expediency of making a variation by printing them in their original shape. But upon considering the matter maturely, his determination to adhere, in all cases, to the text prevailed. If any injury to the reputation of Mr. Adams for prophecy should ensue, it will be more in form than in substance, and will not be, perhaps, without compensation in the restoration of the unpublished portion. This friend was a nephew, William S. Shaw. But the letters had been correctly and fully printed before. See Niles’s Principles and Acts of the Revolution, p. 330.

123. Abigail Adams.

Boston, 21 July, 1776.

Last Thursday, after hearing a very good sermon, I went with the multitude into King Street to hear the Proclamation for Independence read and proclaimed. Some field-pieces with the train were brought there. The troops appeared under arms, and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small-pox prevented many thousands from the country), when Colonel Crafts read from the balcony of the State House the proclamation. Great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the balcony was, “God save our American States,” and then three cheers which rent the air. The bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed, and every face appeared joyful. Mr. Bowdoin then gave a sentiment, “Stability and perpetuity to American independence.” After dinner, the King’s Arms were taken down from the State House, and every vestige of him from every place in which it appeared, and burnt in King Street. Thus ends royal authority in this State. And all the people shall say Amen.

I have been a little surprised that we collect no better accounts with regard to the horrid conspiracy at New York; and that so little mention has been made of it here. It made a talk for a few days, but now seems all hushed in silence. The Tories say that it was not a conspiracy, but an association. And pretend that there was no plot to assassinate the General.[149] Even their hardened hearts feel——the discovery——we have in George a match for “a Borgia or a Catiline”—a wretch callous to every humane feeling. Our worthy preacher told us that he believed one of our great sins, for which a righteous God has come out in judgment against us, was our bigoted attachment to so wicked a man. May our repentance be sincere.

FOOTNOTES:

[149] See Irving’s Life of Washington, Vol. II. p. 240.

Source:

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Familiar Letters of John Adams and His Wife Abigail Adams During the Revolution, by John Adams and Abigail Adams and Charles Francis Adams is produced by Project Gutenberg and released under a public domain license.