Chapter 9: Competing in International Markets

9.6 Options for Competing in International Markets

French philosopher Michel de Montaigne once quipped that marriage is “a market which has nothing free but the entrance.” When trying to match their goods and services with the promise of love from a new market, executives have multiple entry options—but they should carefully consider each, lest the romance be short-lived.

| Exporting | Exporting involves creating goods at home and then shipping them to another country. Civilian aircraft are a top-ten US export to countries such as Japan, China, Germany, Italy, and France that want to make their skies friendlier for travel. |

| Licensing | Licensing involves granting a foreign company the right to create a company’s product in exchange for a fee. This option is frequently used in manufacturing industries, such as when Coca-Cola licenses their secret formulas to local bottlers (without revealing the formulas, of course). |

| Franchising | Franchising involves “renting” a firm’s brand name and business processes to local entrepreneurs. Curves International has used franchising to bulk up its fitness empire to include over thirty countries. |

| Joint Venture | In a joint venture, two or more organizations each contribute to the creation of a new entity. In a strategic alliance, firms work together cooperatively without forming a new organization. Global Nuclear Fuel Co.—a collaboration among General Electric, Toshiba Corporation, and Hitachi Limited—is an example of a joint venture. |

| Acquisition/Wholly owned Subsidiary | Acquisition/wholly owned subsidiary is when a firm acquires a business operation in a foreign country. The firm fully owns the acquired company. Intel established IPLS—a wholly owned subsidiary in Ireland—to facilitate and manage its research throughout the “Emerald Isle.” Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest producer of pork products and located in Virginia, was acquired by a Chinese company for nearly $5 million. |

| Greenfield/Wholly owned subsidiary | Greenfield/wholly owned subsidiary is when a company enters a foreign country and buys property and constructs their business. This could be a manufacturer building a plant, or a retailer building a store, as opposed to acquiring an existing one. BMW used this approach to build its car manufacturing plant in South Carolina. |

When the executives in charge of a firm decide to enter a new country, they must decide how to enter the country. There are six basic options available: (1) exporting, (2) licensing, (3) franchising, (4) creating a joint venture or strategic alliance (5) acquisition/creating a wholly owned subsidiary, and (6) greenfield/wholly owned subsidiary (Table 9.11). These options vary in terms of how much control a firm has over its operation, how much risk is involved, and what share of the operation’s profits the firm gets to keep.

It is important to note that these options are not exclusively for implementing international strategy. As discussed in Chapter 8, all but exporting are also methods to accomplish corporate strategies in their domestic markets to diversify their portfolio.

As shown in Figure 9.3, there are trade-offs in the selection of the method of entry to another country. These variables are:

- The amount of risk

- The degree of control and ownership

- The potential for profit

Exporting provides the least amount of risk, but also the least amount of control and profit potential. Moving from exporting at one end of the continuum to greenfield on the other end, the amount of risk increases, as does the degree of control/ownership and the potential to make more profit. The most risky method to enter into another country is greenfield, when the investment is high in acquiring land and building facilities, without the advantage of taking over an existing company. However, the venture is totally under the control of the entering company and the profit potential is the highest, although riskiest, as noted.

![XY plot where x axis represents Ownership, Control, and Profit Potential and the y axis represents Investment and Risk. A positive line goes straight through the plot with slope=1. Text boxes are placed on the line. From bottom to top: 'Exporting', 'Licensing', 'Franchising' (these 3 boxes are captioned contractual and non-equity-based). 'Strategic Alliance' (captioned non-equity or equity-based: contractual agreements, cross-shareholdings). 'Joint Venture,' 'Wholly Owned Subsidary' (captioned Foreign Direct Investments [FDI], equity-based). The 'Wholly Owned Subsidary is also independently captioned (Greenfield, Acquisition).](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/sites/1889/2020/05/enteringinternationalmarkets.png)

Exporting

Exporting involves creating goods within a firm’s home country and then shipping them to another country. Once the goods reach foreign shores, the exporter’s role is over. A local firm then sells the goods to local customers. Many firms that expand overseas start out as exporters because exporting offers a low-cost method to find out whether a firm’s products are appealing to customers in other lands. Some Asian automakers, for example, first entered the US market through exporting. Small firms may rely on exporting because it is a low-cost and lower risk option.

Once a firm’s products are found to be viable in a particular country, exporting often becomes undesirable. A firm that exports its goods loses control of them once they are turned over to a local firm for sale locally. This local distributor may treat customers poorly and thereby damage the firm’s brand. Also, an exporter only makes money when it sells its goods at wholesale prices to a local firm, not when end users buy the goods. Executives may want their firm to enjoy the profits that are made when products are sold to individual customers rather than a local distributor.

Licensing

While franchising is an option within service industries, licensing is most frequently used in manufacturing industries. Licensing involves granting a foreign company the right to create a company’s product within a foreign country in exchange for a fee. These relationships often center on patented technology. A firm that grants a license avoids absorbing a lot of costs, but its profits are limited to the fees that it collects from the local firm. The firm also loses some control over how its technology is used.

A historical example involving licensing illustrates how rapidly events can change within the international arena. By the time Japan surrendered to the United States and its Allies in 1945, World War II had crippled the country’s industrial infrastructure. In response to this problem, Japanese firms imported a great deal of technology, especially from American firms. When the Korean War broke out in the early 1950s, the American military relied on Jeeps made in Japan using licensed technology. In just a few years, a mortal enemy had become a valuable ally.

Strategy at the Movies

Gung Ho

Can American workers survive under Japanese management? Although this sounds like the premise for a bad reality TV show, the question was a legitimate consideration for General Motors (GM) and Toyota in the early 1980s. GM was struggling at the time to compete with the inexpensive, reliable, and fuel-efficient cars produced by Japanese firms. Meanwhile, Toyota was worried that the US government would limit the number of foreign cars that could be imported. To address these issues, these companies worked together to reopen a defunct GM plant in Fremont, California in 1984 that would manufacture both companies’ automobiles in one facility. The plant had been the worst performer in the GM system; however, under Toyota’s management, the New United Motor Manufacturing Incorporated (NUMMI) plant became the best factory associated with GM—using the same workers as before! Despite NUMMI’s eventual success, the joint production plant experienced significant growing pains stemming from the cultural differences between Japanese managers and American workers.

The NUMMI story inspired the 1986 movie Gung Ho in which a closed automobile manufacturing plant in Hadleyville, Pennsylvania, was reopened by Japanese car company Assan Motors. While Assan Motors and the workers of Hadleyville were both excited about the venture, neither was prepared for the differences between the two cultures. For example, Japanese workers feel personally ashamed when they make a mistake. When manager Oishi Kazihiro failed to meet production targets, he was punished with “ribbons of shame” and forced to apologize to his employees for letting them down. In contrast, American workers were presented in the film as likely to reject management authority, prone to fighting at work, and not opposed to taking shortcuts.

When Assan Motors’ executives attempted to institute morning calisthenics and insisted that employees work late without overtime pay, the American workers challenged these policies and eventually walked off the production line. Assan Motors’ near failure was the result of differences in cultural norms and values. Gung Ho illustrates the value of understanding and bridging cultural differences to facilitate successful cross-cultural collaboration, value that was realized in real life by NUMMI.

Franchising

Franchising is a popular way for firms to grow internationally. Below are examples of US-based franchises that are successful worldwide.

| Successful US-based Franchises |

| In many Asian countries, McDonald’s franchises offer side dishes such as rice alongside its signature French fries. |

| If you grow tired of strudel while in Germany, remember that Dunkin’ Donuts has over 3,200 stores in 36 countries outside of the United States. |

| Legend says that the first sandwich was created when John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich, ordered meat tucked between bread so he could play cards and eat at the same time. The sandwich remains popular in Europe, where Subway boasts over one thousand franchised restaurants. |

| All KFCs in Japan prominently feature a statue of KFC’s founder Colonel Sanders. |

| If a franchised store in Norway was open during the age of the Vikings, its slogan may have been “Thank Asgard for 7-11.” |

Franchising has been used by many firms that compete in service industries to develop a worldwide presence (Table 9.12). Subway, The UPS Store, and Hilton Hotels are just a few of the firms that have done so. Franchising involves an organization (called a franchiser) granting the right to use its brand name, products, and processes to other organizations (known as franchisees) in exchange for an up-front payment (a franchise fee) and a percentage of franchisees’ revenues (a royalty fee).

Franchising is an attractive way to enter foreign markets because it requires little financial investment by the franchiser. Indeed, local franchisees must pay the vast majority of the expenses associated with getting their businesses up and running. On the downside, the decision to franchise means that a firm will get to enjoy only a small portion of the profits made under its brand name. Also, local franchisees may behave in ways that the franchiser does not approve. For example, KFC was angered by some of its franchisees in Asia when they started selling fish dishes without KFC’s approval. It is often difficult to fix such problems because laws in many countries are stacked in favor of local businesses. Last, franchises are only successful if franchisees are provided with a simple and effective business model. Executives thus need to avoid expanding internationally through franchising until their formula has been perfected.

Joint Ventures and Strategic Alliances

Within each market entry option described earlier, a firm either maintains strong control of operations (wholly owned subsidiary) or it turns most control over to a local firm (exporting, franchising, and licensing). In some cases, however, executives find it beneficial to work closely with one or more local partners in a joint venture or a strategic alliance. In a joint venture, two or more organizations each contribute to the creation of a new entity. In a strategic alliance, firms work together cooperatively, but no new organization is formed. In both cases, the firm and its local partner or partners share decision-making authority, control of the operation, and any profits that the relationship creates.

Joint ventures and strategic alliances are especially attractive when a firm believes that working closely with locals will provide important knowledge about local conditions, facilitate acceptance of their involvement by government officials, or both. In the late 1980s, China was a difficult market for American businesses to enter. Executives at KFC saw China as an attractive country because chicken is a key element of Chinese diets. After considering the various options for entering China with its first restaurant, KFC decided to create a joint venture with three local organizations. KFC owned 51% of the venture; having more than half of the operation was advantageous in case disagreements arose. A Chinese bank owned 25%, the local tourist bureau owned 14%, and the final 10% was owned by a local chicken producer that would supply the restaurant with its signature food item.

Having these three local partners helped KFC navigate the cumbersome regulatory process that was in place and allowed the American firm to withstand the scrutiny of wary Chinese officials. Despite these advantages, it still took more than a year for the store to be built and approved. Once open in 1987, however, KFC was an instant success in China. As China’s economy gradually became more and more open, KFC was a major beneficiary. By the end of 1997, KFC operated 191 restaurants in 50 Chinese cities. By the start of 2019, there were approximately 5,000 KFCs spread across 1,100 Chinese cities. Roughly 90% of these restaurants are wholly owned subsidiaries of KFC—a stark indication of how much doing business in China has changed over the past twenty-five years.

Creating a Wholly Owned Subsidiary: Acquisition and Greenfield

In international strategy, a wholly owned subsidiary is a business operation in a foreign country that a firm fully owns. A firm can develop a wholly owned subsidiary through a greenfield venture, meaning that the firm creates the entire operation itself. This usually means building and operating the facility. Another possibility is purchasing an existing operation from a local company or another foreign operator.

Regardless of whether a firm builds a wholly owned subsidiary “from scratch” or acquires an existing company, having a wholly owned subsidiary can be attractive because the firm maintains complete control over the operation, and gets to keep all of the profits that the operation makes. A wholly owned subsidiary can be quite risky, however, because the firm must pay all of the expenses required to set it up and operate it. Kia, for example, spent $1 billion to build its US factory. Many firms are reluctant to spend such sums in more volatile countries because they fear that they may never recoup their investments.

Section Videos

Global Market Entry Strategy [02:00]

The video for this lesson provides a short explanation of mode of entry to other countries.

You can view this video here: https://youtu.be/a5UaXsYV1aw.

A level Business Revision-Entering International Markets [08:25]

The second video for this lesson is longer, but a more thorough explanation of mode of entry to other countries.

You can view this video here: https://youtu.be/SGoGJEe-ERk.

Key Takeaway

- When entering a new country, executives can choose exporting, licensing, franchising, creating a joint venture or strategic alliance, and creating a wholly owned subsidiary through greenfield or acquisition. The key issues of how much control a firm has over its operation, how much risk is involved, and what share of the operation’s profits the firm gets to keep all vary across these options. Along the continuum from exporting to wholly owned subsidiary, risk, control, and profit potential are least with exporting and highest with the wholly owned subsidiary.

Exercises

- Do you believe that KFC would have been so successful in China today if executives had tried to make their first store a wholly owned subsidiary? Why or why not?

- The typical joint venture only lasts a few years. Why might joint ventures dissolve so quickly?

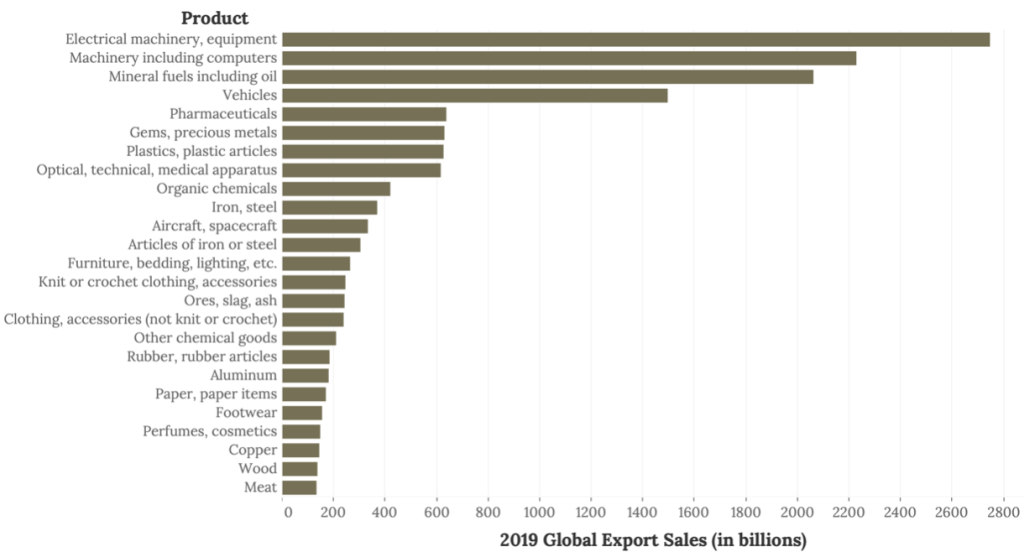

Image Credits

Figure 9.15: Kindred Grey (2020). “Entering International Markets.” CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Entering_International_Markets.png.

Figure 9.16: Mar-Law. Cargo Ship in Channel. CC BY-NC 2.0. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/seenlikethis/3032668425/ Edited photo to add brightness.

Figure 9.17: Kindred Grey (2020). “2019 World Exports by Product.” CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2019_World_Exports_by_Product.png. Data retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_trade.

Figure 9.18: Anonyme. “Assembly line at Hyundai Motor Company’s car factory in Ulsan, South Korea.” CC BY 2.5. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hyundai_car_assembly_line.jpg.

Figure 9.20: Juxun, Chen. “KFC Restaraunt in China.” CC BY-SA 3.0. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kfc_of_china.jpg.

Video Credits

Lyana Lan. (2014, November 21). Global market entry strategy [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/a5UaXsYV1aw.

TakingtheBiz. (2020, March 2). A level business revision-entering international markets [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/SGoGJEe-ERk.