Chapter 7: The ethics of belief

Pragmatic arguments and the ethics of belief

Matthew Van Cleave

Pascal’s wager

Suppose that there are no conclusive arguments either for the existence of god or against the existence of god. Suppose further that the evidence regarding god’s existence is 50/50: there are as many reasons for disbelieving there is a god as there are for believing there is a god. Would it be rational for us to believe in god, even in the absence of compelling evidence that god exists? Or does the absence of compelling evidence mean that we should be agnostic?[1] This is the background to a famous argument from the philosopher and mathematician, Blaise Pascal (1623-1662). Pascal believed that human reason will not be able to settle the matter of whether god exists, but he also thought that whether one believes that god exists is a vital issue that concerns one’s wellbeing—even if not in this life, then in the next. Pascal’s claim is that it is in our rational self-interest to believe that god exists. Pascal’s argument is often referred to as Pascal’s Wager.[2]

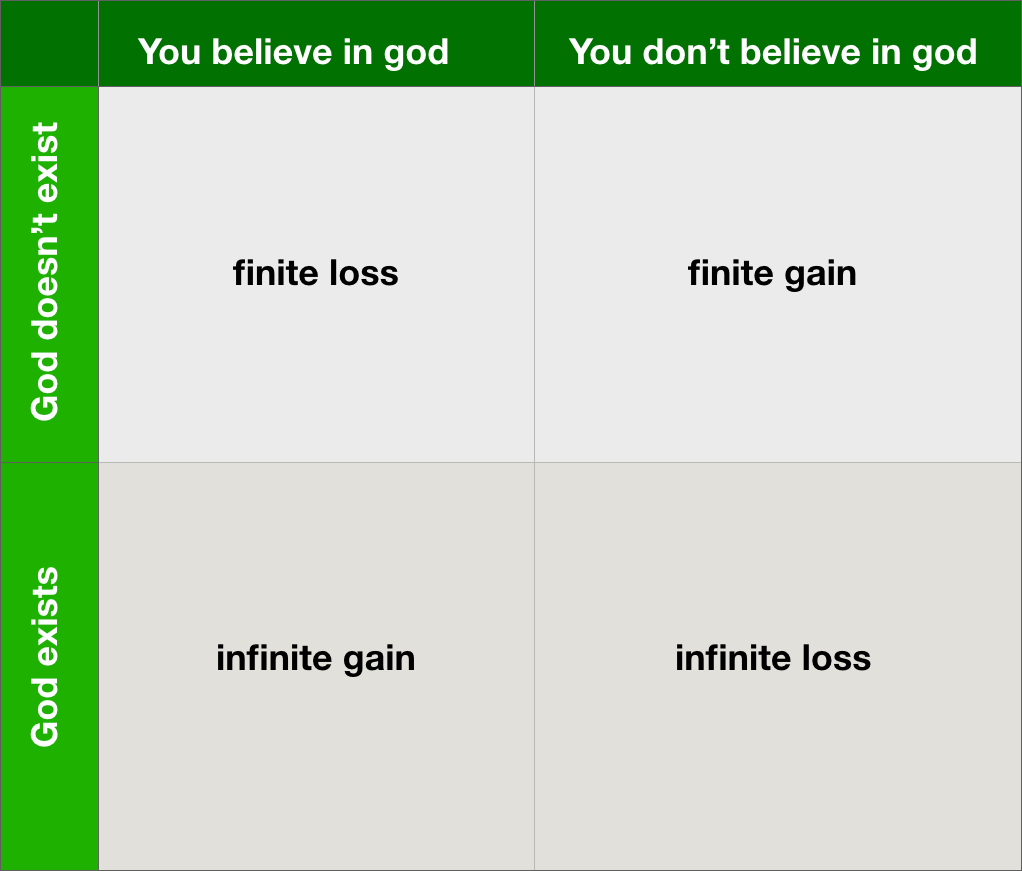

Consider a commonly held Christian (and Muslim) view, according to which there is a heaven, where believers will go and experience infinite bliss after they die, and a hell, where non-believers will live an eternity in torment and suffering. Given that we do not know that this is true, Pascal’s point is that we can still ask whether it is rational to believe that it is true. And Pascal’s answer is that it is rational to believe it because it is in our self-interest to believe it. Here’s the reasoning behind the wager: If you believe that god exists and god really does exist, then (after you die) you have an infinite gain. If you believe in god and god doesn’t exist, then you may lose out on some earthly pleasures (as a result of living a good Christian life), but whatever losses those are will be finite. In contrast, if you do not believe that god exists but god really does exist, then you lose out on an infinite reward (and possibly incur an infinite loss). The only other option is that you fail to believe that god exists and god really doesn’t exist. In that case, you may gain some earthly pleasures but those will still be finite in contrast with the potentially infinite pleasures of heaven. The figure below represents all the possible options.

Pascal thinks that it is obvious that the rational thing to choose is to believe in god because of the potentially infinite reward, which would offset any possible finite losses or gains. Therefore, if you don’t already believe in god, it is in your rational self-interest to believe.

Pascal’s is giving us a pragmatic argument: he is not trying to convince us that god actually does exist, but that it is in our self-interest to believe that god exists. Even if god doesn’t exist, it would still be pragmatically rational for us to believe that god exists, given the potentially infinite reward as compared to the finite gains/losses of not believing. Pragmatic reasons for believing something contrast with epistemic reasons for believing because the latter are tied to truth whereas the former are only tied to our self-interest or goals. One of the questions raised by Pascal’s argument is whether we should (or even are able to) believe something for pragmatic reasons. As we will see below, the American philosopher and psychologist, William James, agrees with Pascal that we can and should believe for pragmatic reasons, whereas the English mathematician and philosopher W.K. Clifford thinks that it is morally wrong to believe something for purely pragmatic reasons. We will consider their arguments below.

Pascal’s wager is one of the earliest known examples of the mathematical field of decision theory. Decision theory attempts to describe, in precise mathematical terms, what it is rational to do. Here is a simple example to illustrate the idea.

Example: lets suppose we’re guessing what color of marble has been randomly selected (as in a lottery) from an urn of colored marbles. There are 50 red marbles, 10 green marbles and 5 blue marbles. Suppose we get $10 if a red marble is selected, $100 for a green marble and $500 for a blue marble.

According to decision theory, the rational option to choose is the one that has the highest expected utility. Expected utility of a choice is calculated by taking the choice’s probability multiplied by the choice’s payoff. Thus the expected utility of the different options in this example would be:

- Red = (.5)(10) = 5

- Green = (.1)(100) = 10

- Blue = (.05)(1000) = 50

In this case betting that a blue marble has been selected has the highest expected utility and thus, according to decision theory, would be the most rational bet.

We can apply decision theory to more complicated, real-life examples, as well. All we would need is an agent’s preference ranking of her possible choices and an estimation of the probability that each of those choices has of occurring. The rational thing to do will be the thing that has the highest expected utility.

Importantly, the rational thing to do will be relative to our different desires (preference rankings). I may assign a really high utility to A and a low utility to B, whereas you may do the opposite. In that case, what it is rational for me to do is not what it is rational for you to do.

What is unique to Pascal’s wager is that some of the choices are supposed to have an infinite payoff (in this case, the eternal bliss of heaven, if it exists).

Although Pascal himself set the probability of god’s existence at 50%, since the payoff is infinite, it doesn’t matter how low we set the probability of god’s existence. If the payoff is infinite then the expected utility is infinite even if the probability is low. For example, even if we set the probability of god’s existence at one in one hundred billion, the infinite payoff would still yield an infinite expected utility: (.00000000001)(∞) = ∞. Thus, although Pascal doesn’t explicitly do so, one could try to extend his argument even to situations where god’s existence is much less likely than god’s nonexistence.Note, also that even if we add in the costs of believing in god, as long as the costs are finite then the expected utility will still be infinite. We can set the costs of wagering against God at zero. Pascal thinks that there is little or no payoff for one who wagers against God.

There’s a problem with the idea of believing for pragmatic reasons that Pascal anticipates and responds to and that is this: one can’t make oneself believe something that ones has no compelling reason to think is true. For example, I cannot simply make myself believe that there is $100 in my pocket, even if I would very much like for it to be true that there is $100 in my pocket. Pascal’s agrees that you cannot simply make yourself believe something you don’t feel is true, but he thinks that you can do things that will change the way you feel. Here is what Pascal says:

Endeavour then to convince yourself, not by increase of proofs of God, but by the abatement of your passions. You would like to attain faith, and do not know the way; you would like to cure yourself of unbelief, and ask the remedy for it. Learn of those who have been bound like you, and who now stake all their possessions. These are people who know the way which you would follow, and who are cured of an ill of which you would be cured. Follow the way by which they began; by acting as if they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, and so on. Even this will naturally make you believe, and deaden your acuteness.

In short, Pascal’s response is: fake it until you make it.

The ethics of belief

The British philosopher W.K. Clifford couldn’t disagree more with this. According to Clifford, our beliefs have consequences and being careless with our beliefs can have horrible consequences on other people. Because this is true, Clifford argues that we have an ethical duty to uphold stringent standards for what we allow ourselves to believe. In short, Clifford thinks that we have a moral duty to proportion our belief to the evidence. Thus, if the evidence for a particular claim is not sufficiently strong, then we should not believe that claim. So in a case like Pascal’s where the evidence for god’s existence is equivocal, we should neither believe that god exists nor believe that god doesn’t exist. That is, we should be agnostic with respect to god’s existence. According to Clifford, only evidence should drive what we believe, never our self-interest or what we wish were true. What Clifford is rejecting, then, is what we have called “pragmatic arguments”: arguments that attempt to establish that we ought to believe something even in the absence of sufficient evidence that that thing is true. Clifford’s view has become known as the “ethics of belief” (after the title of Clifford’s 1877 article). The ethics of belief, then, is the claim that we have an ethical duty to believe only those things for which we have sufficient evidence. The ethics of belief stands in diametric opposition to pragmatic arguments like Pascal’s.

Clifford’s argument for the ethics of belief turns on a story that he tells about a ship owner. Here is that story:

A ship owner was about to send to sea an emigrant ship. He knew that the ship was old and not well built, that it had seen many voyages, and that it often had needed repairs. People had suggested to him that possibly the ship was not seaworthy. These doubts preyed upon his mind, and made him unhappy; he thought that perhaps he ought to have the ship thoroughly overhauled and repaired, even though this would cost him a lot of money. Before the ship sailed, however, he succeeded in overcoming these doubts. He said to himself that the ship had gone safely through so many voyages and weathered so many storms that it would probably come safely home from this trip also. He would put his trust in God, which of course would protect all these unhappy families that were leaving their fatherland to seek for better times elsewhere. He would dismiss from his mind all doubts about the honesty of the ship builders. In such ways he acquired a sincere belief that his ship was thoroughly safe and seaworthy; he watched her departure with a light heart, and warm wishes for the success of the exiles in their strange new home; and he got his insurance-money when she went down in mid- ocean and told no tales.[3]

What Clifford’s ship owner is doing here seems to be exactly what Pascal’s questioner (who doesn’t believe in god) is doing: they are both stifling doubts and a lack of belief by undertaking actions that will enable them to believe. In Pascal’s case, that is by acting as if one believed (going to mass, taking holy water); in the case of Clifford’s ship owner, that is by a kind of hopeful self-talk that enables him to overcome evidence to the contrary (the ship is old, not well- built, people suggesting that it wasn’t seaworthy). However, in the case of Clifford’s ship owner the action of stifling doubts is at the cost of people’s lives and thus it seems that what the ship owner did was negligent and wrong. It doesn’t matter that the ship owner believed that the ship would be fine; he had a duty not to believe it because of the evidence to the contrary. Here is what Clifford says:

What shall we say of him? Surely this, that he was truly guilty of the death of those men. It is admitted that he did sincerely believe in the soundness of his ship; but the sincerity of his conviction does not exonerate him, because he had no right to believe on the evidence he had. He had acquired his belief not by honestly earning it in patient investigation, but by stifling his doubts. And although in the end he may have felt so sure about it that he could not think otherwise, yet inasmuch as he had knowingly and willingly worked himself into that frame of mind, he must be held responsible for it.

So the ship owner example is a clear case where a non-evidence-based belief (wishful thinking) led to a horrible outcome. If the ship owner had done his ethical duty he would have investigated whether the ship really was seaworthy rather than simply relying on wishful thinking. Thus it is wishful thinking that seems to be at fault here. As Clifford later notes, even if the ship had made a successful voyage, it still seems that the ship owner did something morally wrong because of the risk he put others in. Consider an analogy: even if a very drunk driver were able to make it home safely and didn’t cause any harm, that doesn’t make his action morally permissible. The fact is, he was putting others at risk and that is what makes that action wrong.

But what about cases where my wishful thinking is not harming others or even posing any substantial risk of harm? Return to Pascal’s case of the person who doesn’t believe that god exists but who is able to work themselves into that belief over time. What does it matter if this person believes in god or not? How is that hurting anyone? Or, to take a different case, consider someone who really, really wants unicorns to be real but doesn’t currently believe they are real. In order to acquire this belief, this person spends most of their time with other people who also believe in unicorns and dismisses or ignores or explains away evidence to the contrary and basically does all the kinds of things the Clifford’s ship owner does. Eventually, like Pascal’s fake-it-until-you-make-it believer, this person comes to sincerely believe that unicorns exist. However, in this case it seems like a stretch to say that what this person has done is morally wrong because this person’s belief doesn’t seem to be harming anyone. What would Clifford say about a case of wishful thinking like this one? Isn’t it importantly different from his ship owner case?

Clifford’s response takes a step back to consider the general effects on society of believing things based on insufficient evidence. Clifford’s claim is that by allowing ourselves to believe things without sufficient evidence, we weaken our powers of critical awareness upon which a vibrant, healthy society depends. If anyone can believe anything for any reason, Clifford fears that ultimately the fabric of society will unravel because a healthy society depends on people being able to trust others as a source of knowledge. Credulous people cannot be trusted. Here’s Clifford in his own words:

Every time we let ourselves believe for unworthy reasons, we weaken our powers of self-control, of doubting, of judicially and fairly weighing evidence. We all suffer severely enough from the maintenance and support of false beliefs and the fatally wrong actions which they lead to, and the evil born when one such belief is entertained is great and wide. But a greater and wider evil arises when the credulous character is maintained and supported, when a habit of believing for unworthy reasons is fostered and made permanent. …[I]f I let myself believe anything on insufficient evidence, there may be no great harm done by the mere belief; it may be true after all, or I may never have occasion to exhibit it in outward acts. But I cannot help doing this great wrong towards Man, that I make myself credulous. The danger to society is not merely that it should believe wrong things, though that is great enough; but that it should become credulous, and lose the habit of testing things and inquiring into them; for then it must sink back into savagery.

The harm which is done by credulity in a man is not confined to the fostering of a credulous character in others, and consequent support of false beliefs. Habitual want of care about what I believe leads to habitual want of care in others about the truth of what is told to me. Men speak the truth to one another when each reveres the truth in his own mind and in the other’s mind; but how shall my friend revere the truth in my mind when I myself am careless about it, when I believe things because I want to believe them, and because they are comforting and pleasant? Will he not learn to cry, “Peace,” to me, when there is no peace? By such a course I shall surround myself with a thick atmosphere of falsehood and fraud, and in that I must live. It may matter little to me, in my cloud-castle of sweet illusions and darling lies; but it matters much to Man that I have made my neighbors ready to deceive. The credulous man is father to the liar and the cheat; he lives in the bosom of this his family, and it is no marvel if he should become even as they are. So closely are our duties knit together, that whoso shall keep the whole law, and yet offend in one point, he is guilty of all.

Here is one way of reconstructing Clifford’s argument:

- If we believe things on insufficient evidence, we weaken our powers of being critical, doubting, and carefully weighing evidence.

- Individuals’ whose critical powers are weakened are more credulous.

- When individuals are credulous they are easier to deceive and less trustworthy sources of information.

- If individuals are easier to deceive, there will tend to be more deception.

- If individuals are less trustworthy, then they will tend not to be trusted.

- Therefore, a society in which individuals believe things on insufficient evidence would tend to be a society in which there is more deception and less trust. (from 1-5)

- A society in which there is more deception and less trust is a worse society.

- We ought not do things which will create a worse society.

- Therefore, we ought not believe things on insufficient evidence. (from 6-8)

So, like the ship owner case, Clifford thinks that there is a general kind of harm (a “harm to Man”) that is caused by believing things on insufficient evidence, regardless of what the specific belief is. The issue for Clifford is not the truth of the belief, but the process by which we come to believe it. He thinks that believing things too quickly and easily actively harms society. Clifford thinks we have an ethical duty to be critical of what we come to believe. In a famous passage Clifford notes,

If a man, holding a belief which he was taught in childhood or persuaded of afterwards, keeps down and pushes away any doubts which arise about it in his mind, purposely avoids the reading of books and the company of men that call into question or discuss it, and regards as impious those questions which cannot easily be asked without disturbing it—the life of that man is one long sin against mankind.

How should we assess Clifford’s argument? Is he right that there is something wrong with believing things we want to be true without looking carefully at the evidence? Are the results for society as dire as Clifford warns? One thing to be wary about in Clifford’s argument is the possibility of a slippery slope fallacy. Note that premises 1-5 are all conditional statements—statements of the form “if A then B.” The form of the first part of the argument goes like this:

- If A then B

- If B then C

- If C then D

- If D then E

- Therefore, if A then E

In logic, this is called a hypothetical syllogism; notice how each premise functions like a link in a chain where the conclusion links the first link (A) with the last link (E). However, notice the most plausible reading of those premises is not that every time x occurs, y occurs but that most of the times x occurs y occurs (this is clear from the language of “tends to” in some of the premises). In this case even if each of the five conditional statements were fairly probable (for example, B might follow from A 80% of the time), when we link them all together, the conclusion is no longer probable. This is because of how probability works: the probability of the conclusion decreases the more probabilistic conditional statements you add. Since the above reconstruction of Clifford’s argument contains four probabilistic conditional statements, the likelihood of the conclusion is: .8 x .8 x .8 x .8 = .41. That means the conclusion is actually very unlikely! That is not a strong argument. This is one reason to doubt that Clifford’s claims about the negative effects of wishful thinking on society are as bad as he worries they are.

One thing that bears on Clifford’s argument and that was discovered long after Clifford was alive is what psychologists call “confirmation bias.” Confirmation bias is a cluster of phenomena that all have in common the idea that we are more likely to believe something that we want/wish to be true.[4] What psychologists have shown over the last few decades is that individuals are less likely to pay attention to evidence that disconfirms something they believe than to evidence that confirms it. Moreover, individuals will tend to forget evidence that challenges an existing belief and more likely to remember evidence that supports it. This is exactly the kind of thing that Clifford was saying that we shouldn’t do, but what psychologists have discovered is that we all in fact do do it. A liberal will exhibit confirmation bias in favor of her liberal beliefs; a conservative will exhibit confirmation bias in favor of her conservative beliefs.

And so on for every other social category we can imagine, including atheists! The facts that the trait that Clifford was warning against is so widespread might be taken to reinforce Clifford’s argument. One way of objecting to Clifford’s argument, for example, would be to say that he is just wrong about how credulous humans tend to be. But the evidence that psychologists have gathered over the decades on confirmation bias defuses this objection: we all have the tendency to believe what we want to believe. But, again, the question is whether this is such a bad thing?

Here is one reason for thinking that it is a bad thing and that we should, instead, foster exactly the kind of critical awareness that Clifford recommends. In an increasingly polarized era, where politics increasingly feels like a team sport and there is precious little quality conversation between groups that hold opposing views, one might worry about the health of the democracy. If we all surround ourselves with only those who tend to share our views, perhaps healthy political discourse will break down. Perhaps it already has. Political discourse seems not to be driven by evidence but, rather, by forgone conclusion that each side is to accept, regardless of evidence. If that is at all a somewhat accurate diagnosis of the current state of politics in the United States (and also elsewhere in the world), then perhaps fostering a more critical attitude towards one’s own beliefs would be salutary. Maybe other domains of life, including religion, would also become less susceptible to confirmation bias and hence less polarized if we were to foster a more critical attitude towards our beliefs, tying them more strongly to evidence as Clifford suggests we ought to. The point of the foregoing is that given that we now know (scientifically) that human beings are naturally susceptible to the vices of credulity that Clifford warns against, perhaps this provides a further reason for thinking that Clifford was onto something, even if he sometimes comes off, in the words of William James, “with somewhat too much of robustious pathos in the voice.”[5]

The will to believe

In his famous essay, “The Will to Believe,” the American philosopher and psychologist, William James (brother of the famous novelist Henry James) argues against Clifford’s “ethics of belief.” James thinks that there are plenty of cases where it is not morally wrong to believe something without sufficient evidence. James takes himself to be arguing in support of Pascal’s position that it is sometimes ok to believe certain things for pragmatic reasons. James thinks that pragmatic reasons are always context-specific—that is, they only work for beliefs that are already “live options” for us in our specific cultural contexts. But what determines which things are considered live options in a particular cultural context is almost never evidence, but other emotional and volitional (desire- based) factors. James makes this point with religious belief, specifically, which is the not-so-subtle subtext lurking behind the whole debate on the ethics of belief. Commenting on Pascal’s wager, he says:

You probably feel that when religious faith expresses itself thus, in the language of the gaming-table, it is put to its last trumps. Surely Pascal’s own personal belief in masses and holy water had far other springs; and this celebrated page of his is but an argument for others, a last desperate snatch at a weapon against the hardness of the unbelieving heart. We feel that a faith in masses and holy water adopted willfully after such a mechanical calculation would lack the inner soul of faith’s reality; and if we were ourselves in the place of the Deity, we should probably take particular pleasure in cutting off believers of this pattern from their infinite reward. It is evident that unless there be some pre-existing tendency to believe in masses and holy water, the option offered to the will by Pascal is not a living option. Certainly no Turk ever took to masses and holy water on its account; and even to us Protestants these means of salvation seem such foregone impossibilities that Pascal’s logic, invoked for them specifically, leaves us unmoved. As well might the Mahdi write to us, saying, “I am the Expected One whom God has created in his effulgence. You shall be infinitely happy if you confess me; otherwise you shall be cut off from the light of the sun. Weigh, then, your infinite gain if I am genuine against your finite sacrifice if I am not!” His logic would be that of Pascal; but he would vainly use it on us, for the hypothesis he offers us is dead. No tendency to act on it exists in us to any degree.

James’s point is that pragmatic arguments only work for beliefs that are already live options for us. But how those beliefs come to be live options in the first place, is rarely a matter of evidence:

It is only our already dead hypotheses that our willing nature is unable to bring to life again. But what has made them dead for us is for the most part a previous action of our willing nature of an antagonistic kind. When I say ‘willing nature,’ I do not mean only such deliberate volitions as may have set up habits of belief that we cannot now escape from,—I mean all such factors of belief as fear and hope, prejudice and passion, imitation and partisanship, the circumpressure of our caste and set. As a matter of fact we find ourselves believing, we hardly know how or why. Mr. Balfour gives the name of ‘authority’ to all those influences, born of the intellectual climate, that make hypotheses possible or impossible for us, alive or dead. Here in this room, we all of us believe in molecules and the conservation of energy, in democracy and necessary progress, in Protestant Christianity and the duty of fighting for ‘the doctrine of the immortal Monroe,’ all for no reasons worthy of the name. We see into these matters with no more inner clearness, and probably with much less, than any disbeliever in them might possess. His unconventionality would probably have some grounds to show for its conclusions; but for us, not insight, but the prestige of the opinions, is what makes the spark shoot from them and light up our sleeping magazines of faith. Our reason is quite satisfied, in nine hundred and ninety-nine cases out of every thousand of us, if it can find a few arguments that will do to recite in case our credulity is criticized by some one else. Our faith is faith in some one else’s faith, and in the greatest matters this is most the case. Our belief in truth itself, for instance, that there is a truth, and that our minds and it are made for each other,—what is it but a passionate affirmation of desire, in which our social system backs us up? We want to have a truth; we want to believe that our experiments and studies and discussions must put us in a continually better and better position towards it; and on this line we agree to fight out our thinking lives. But if a pyrrhonistic skeptic asks us how we know all this, can our logic find a reply? No! certainly it cannot. It is just one volition against another,—we willing to go in for life upon a trust or assumption which he, for his part, does not care to make.

James is treading deep philosophical waters here at the end of this passage. He is noting that many of the things we believe, including things like that there is an external world at all, are not underwritten by evidence-based reasons. How can you defeat the skeptic with evidence, after all?[6] Or consider the idea that a good society is one that protects those who are vulnerable and not capable of

protecting themselves. Can you prove that with reasons or evidence? It seems not since it is such a basic and obvious point to us—not in need of further justification. James’s point is that there are many types of beliefs that we do not have sufficient evidence for and religious belief is one of them. In cases like these, we do nothing morally wrong in holding onto the belief, contrary to what Clifford claims.

As James sees it, Clifford is mistaken in thinking that there is something morally wrong with believing things without sufficient evidence. The specific beliefs that James focuses on are moral beliefs, interpersonal relationship beliefs, and religious beliefs. James has us consider two belief-forming policies:

- Clifford’s policy: believe only that for which you have sufficient evidence

- James’s policy: believe live options when they are important for your life, even if you don’t have sufficient evidence for them

James claims that although following Clifford’s policy would tend to result in having true beliefs (because it’s a stricter policy), it would also potentially cause you to miss out on some truths that didn’t reveal themselves so easily. Suppose the universe were such that there was a god, but that god didn’t reveal themself unless people were willing to take a leap of faith in the first place. If that were so, then someone who followed Clifford’s policy would never be able to acquire the truth about god’s existence. Here is James:

We feel, too, as if the appeal of religion to us were made to our own active good-will, as if evidence might be forever withheld from us unless we met the hypothesis half-way. To take a trivial illustration: just as a man who in a company of gentlemen made no advances, asked a warrant for every concession, and believed no one’s word without proof, would cut himself off by such churlishness from all the social rewards that a more trusting spirit would earn,—so here, one who should shut himself up in snarling logicality and try to make the gods extort his recognition willy- nilly, or not get it at all, might cut himself off forever from his only opportunity of making the gods’ acquaintance. … I, therefore, for one cannot see my way to accepting the agnostic rules for truth-seeking, or willfully agree to keep my willing nature out of the game. I cannot do so for this plain reason, that a rule of thinking which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth if those kinds of truth were really there, would be an irrational rule. That for me is the long and short of the formal logic of the situation, no matter what the kinds of truth might materially be.

James’s argument in “The Will to Believe” thus consists of two separate lines of reasoning, both of which we have already discussed. First, since many of our beliefs are such that they cannot be based wholly on sufficient evidence (since the winnowing down of beliefs to those we see as live options is are driven by cultural forces over which individuals have little control), Clifford’s policy would be unduly restrictive and unfair (and we ought not endorse policies that are unfair). Second, Clifford’s policy would turn us all into skeptics about the important matters of life and we are not morally obligated to be skeptics (being a non-skeptic is not more immoral than being a skeptic). As James notes at the end of “The Will to Believe,”

In all important transactions of life we have to take a leap in the dark… If we decide to leave the riddles unanswered, that is a choice; if we waver in our answer, that, too, is a choice: but whatever choice we make, we make it at our peril. If a man chooses to turn his back altogether on God and the future, no one can prevent him; no one can show beyond reasonable doubt that he is mistaken. If a man thinks otherwise and acts as he thinks, I do not see that any one can prove that he is mistaken. Each must act as he thinks best; and if he is wrong, so much the worse for him.

It is important to note that James has not so much rebutted Clifford’s moral argument as he has given a different argument with a different conclusion. That is, James nowhere discusses the logic of Clifford’s moral argument that was laid out above. Rather, he provides a different argument against Clifford’s conclusion. There’s nothing wrong with that tactic, but it does leave one wondering how Clifford’s argument can be criticized. As often happens in philosophy, we are left with the raw materials to construct our own view on the matter. Both Clifford and James have given interesting arguments for differing conclusions; our task is to knit those somewhat unconnected pieces into a satisfying view.

What might Clifford say in response to James’s argument? One thing I think he might say is that even if it is true that no one’s beliefs are ever totally evidence- based and bias free, it doesn’t follow that we can’t seek to do better. Clifford is clearly not as worried about having false beliefs as he is with a moral duty to consider evidence over wishful thinking. Even if it is true that it is very difficult to eliminate all wishful thinking, as the phenomenon of confirmation bias suggests, that doesn’t mean that we can’t at least try to do better. On this point, perhaps James and Clifford are in agreement. James is not arguing that anyone can believe anything they wish, but that with certain beliefs we cannot base them wholly on evidence. And it seems that Clifford would agree here: even if I cannot refute the moral skeptic, it doesn’t follow that the moral beliefs I have are purely wishful thinking. What about religious belief—what would Clifford say about that? Suppose it turned out (as in James’s scenario above) that there were a god but that god was elusive and didn’t reveal themself to those who didn’t take some steps of blind faith. Presumably Clifford’s tendency would be not to believe in god based on the lack of evidence. If Clifford were to find himself before this god at some point, perhaps he would reply, “Sir why did you not give me better evidence?”[7]

Study questions

- True or false: Pascal thinks that it is very likely that god exists.

- True or false: Pascal’s wager is a pragmatic argument

- True or false: Pragmatic arguments are attempts to get something to believe x, regardless of whether x is true or if there’s good evidence to believe x.

- True or false: Pascal’s wager is one of the earliest examples of decision theory.

- True or false: Clifford thinks that false beliefs are morally wrong.

- True or false: Clifford thinks that what makes the ship owner’s action wrong is that his false belief caused others harm.

- True or false: Clifford thinks that as long as what I believe doesn’t directly harm anyone, then I should be allowed to believe it—even if it is not supported by sufficient evidence.

- True or false: What psychologists call “confirmation bias” is exactly the kind of thing that Clifford railed against—a kind of wishful thinking (or believing).

- True or false: James thinks that most of our beliefs are driven only by evidence.

- True or false: James thinks that if we were to follow Clifford’s policy then it would turn us into skeptics—specifically skeptics about moral and religious truths.

- True or false: Clifford thinks that it is permissible to believe some things that aren’t based on sufficient evidence.

- True or false: James thinks that it is permissible to believe some things that aren’t based on sufficient evidence.

- True or false: Pascal thinks that it is permissible to believe some things that aren’t based on sufficient evidence.

For deeper thought

- In William James’s “Will to Believe,” James construes Clifford’s position as being driven by the fear of being wrong (that is, by the fear of having false beliefs). James points out that the fear of being wrong is itself something “passional” (meaning “emotional”) and thus not purely rational or evidential. Thus, he thinks Clifford is being hypocritical in a certain sort of way. Do you think that James has accurately captured Clifford’s view, based on what was presented above, or has James committed a straw man fallacy? Why or why not?

- What do you think about James’s idea that there are certain things in life that require a leap of faith before you can see them to be true? Are there things in life like this? If so, how do you think Clifford would respond? Would he think that it is wrong to pursue something that we think might be true in order to see if it is true?

- Consider the examples that William James puts forward in section IX of “The Will to Believe.” Do you think that all of these examples are cases in which the individuals need to believe x is true or do they only need to hope x is true?

- Why does Clifford think that it is immoral to believe on insufficient evidence even when no one will be directly harmed by those beliefs?

- “Agnostic” comes from the Greek word “gnosis” meaning “knowledge.” The prefix “a” in Greek means “no” or “not.” Hence, “agnostic” means literally “no knowledge.” An agnostic is a person who neither believes nor disbelieves something. Thus an agnostic concerning god is someone who neither believes nor disbelieves in god. ↵

- The wager occurs in Pascal’s Pensées, which is basically a collection Pascal’s journal entries— his “thoughts” (“pensées” is Latin for “thoughts”). ↵

- Both here and in the following passages from Clifford, I have slightly updated Clifford’s English to make it more modern and readable for students. ↵

- For a scholarly review of the phenomenon of confirmation bias, see Raymond Nickerson, “Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises” in Review of General Psychology, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 175-220. The general idea of confirmation bias is not new, however. The philosopher Aurthur Shopenhauer anticipated it in 1819: “A hypothesis, conceived and formed, makes us lynx-eyed for everything that confirms it, and blind to everything that contradicts it. What is opposed to our party, our plan our wish, our hope often cannot possibly be grasped and comprehended by us, whereas it is clear to the eyes of everyone else” (World as Will and Representation, vol. 2). ↵

- This line is from William James’s famous essay, “The Will to Believe” (section III) which will be discussed in the next section. ↵

- For more on external world skepticism, see that chapter in this textbook. ↵

- This is actually a famous response from the philosopher Bertrand Russell who was once asked in an interview in the Saturday Review (1974): "Let us suppose, sir, that after you have left this sorry vale, you actually found yourself in heaven, standing before the Throne. There, in all his glory, sat the Lord—not Lord Russell, sir: God." Russell winced. "What would you think?" "I would think I was dreaming." "But suppose you realized you were not? Suppose that there, before your very eyes, beyond a shadow of a doubt, was God. What would you say?" The pixie wrinkled his nose. "I probably would ask, 'Sir, why did you not give me better evidence?' " ↵